Meanwhile, its leaders aren’t invited to talks on the future of Ukraine

Europe has been kneed below the belt by the US and is still gasping for breath, the pro-Kremlin newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets said yesterday.

So what? It was merely speaking the truth. As was Donald Trump’s defence secretary when he said last week Europe had fallen into “dependency” on the US for its security.

- Europe’s inability to defend itself is the reason the US can launch a Russia-Ukraine peace process in Saudi Arabia today without Ukraine or Europe present.

- It’s also the reason European leaders rushed to Paris yesterday seized by a sudden determination to fix a problem that has been lying in plain sight since the cold war.

Paris summit. They had plenty of ideas, not all compatible.

- The UK’s Keir Starmer suggested an American “backstop” – which experts took to mean air cover and intelligence support – having offered to put British boots on the ground in Ukraine as part of a peace deal.

- German’s Olaf Scholz said talk of boots was premature and insisted the US and Europe had to stick together for Ukraine.

- Poland’s Donald Tusk backed Scholz on unity but said an immediate defence funding boost across Europe was most important.

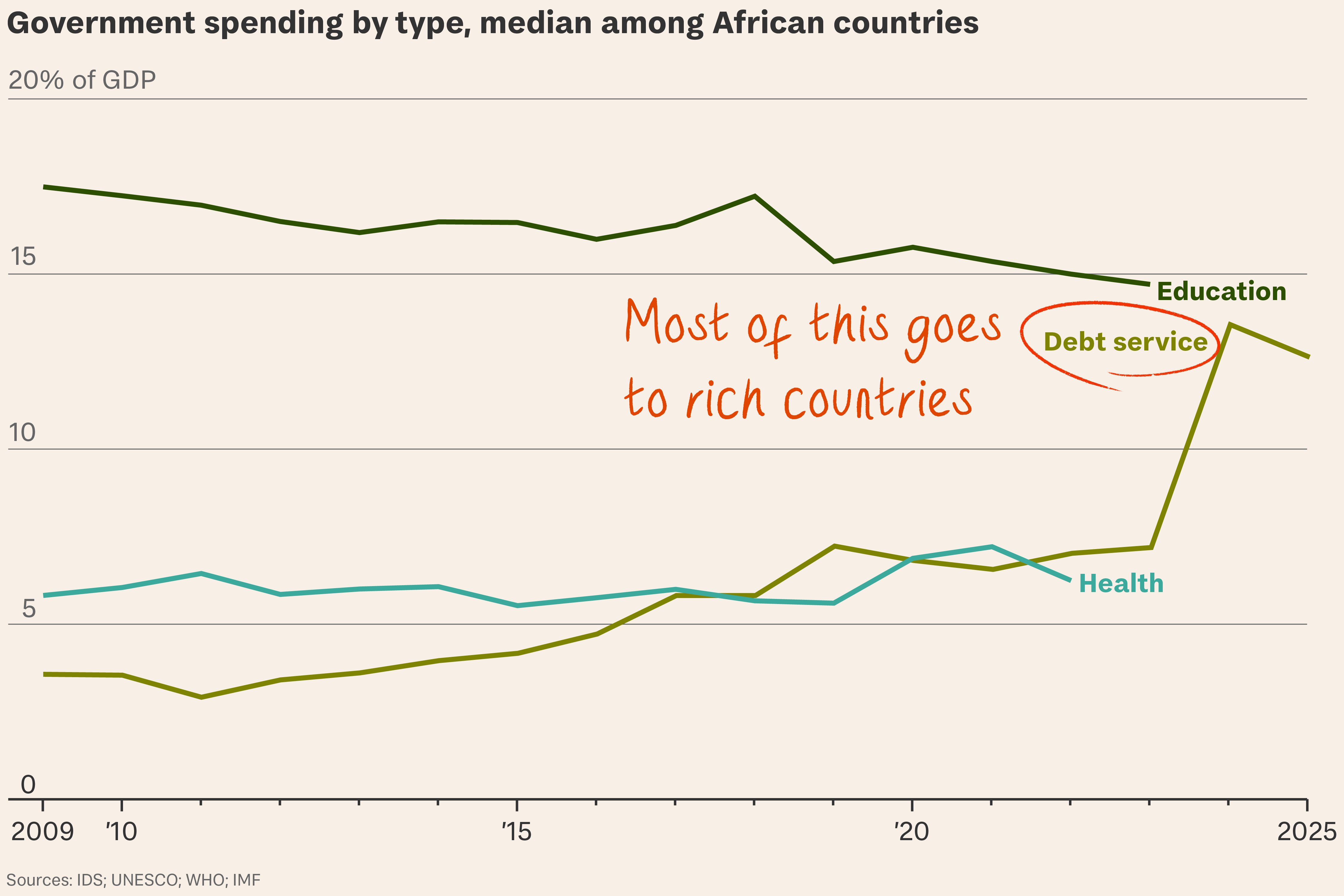

Easy prey. If all Nato’s European members matched Poland’s defence spending at 5 per cent of GDP they could compensate eventually for an end to US military aid to Ukraine and even a US withdrawal from Nato. But that’s a big if. Europe’s defencelessness has many roots. They are

- geographical – there are no natural frontiers between Russia and Europe that can’t be crossed with pontoon bridges;

- historical – Germany has been reluctant to deploy force since World War Two, and Nato has traditionally advised the EU against duplicating its command structures;

- organisational – Nato has 32 members and 32 armies;

- technical – the EU’s armies alone operate 178 different weapons systems compared with about 30 operated by the US;

- strategic – Europe’s two nuclear powers, the UK and France, have about 515 nuclear warheads between them compared with Russia’s 4380; and

- economic – average non-EU Nato spending on armoured fighting vehicles, fast jets and submarines fell by between half and three quarters between 1994 and 2024 (and for much of that period Europe funded Russia’s rearmament by buying its oil and gas).

And yet, less reported than its weaknesses, Europe boasts strengths and defence initiatives that give hope.

It’s not poor. On the contrary. As Harvard’s Steven Walt has noted, Europe’s economies combined are ten times the size of Russia’s. They have three times as many people and as of last year spent three times as much on defence, two thirds reaching or exceeding Nato’s minimum defence spend of 2 per cent of GDP .

It’s not supine. On the contrary, in addition to taking part in mammoth Nato exercises designed to impress Russia…

- Poland, Germany and the Netherlands have signed a “military Schengen” agreement to streamline troop mobility in participating states.

- France, Germany, Spain and Airbus have joined forces to build a “future combat air system” based on drones, satellites and sixth-generation fighters.

- Sweden, Finland, Norway and Denmark have launched the Nordic Air Defence Alliance, which aims to have 250 planes combat-ready by 2030.

- As of last September the EU has its first defence and space commissioner in Andrius Kubilius, a former Lithuanian prime minister.

It’s not rocket science. “How much [military] equipment Europeans can generate to compensate for the loss of US support – that’s the question for 2025,” Ivo Daalder, a former US ambassador to Nato, told Tortoise at the start of the year. The question hasn’t changed; it’s just become more urgent.

What’s more… what Europeans can’t make they can always buy from the US, which might curry favour with its president.