Debt relief that could improve the life of millions

Donald Trump’s tariffs are set to shave half a percentage point off global growth, the International Monetary Fund said on Tuesday. The IMF warned that poor countries already hit by Trump’s gutting of foreign aid could plunge further into debt.

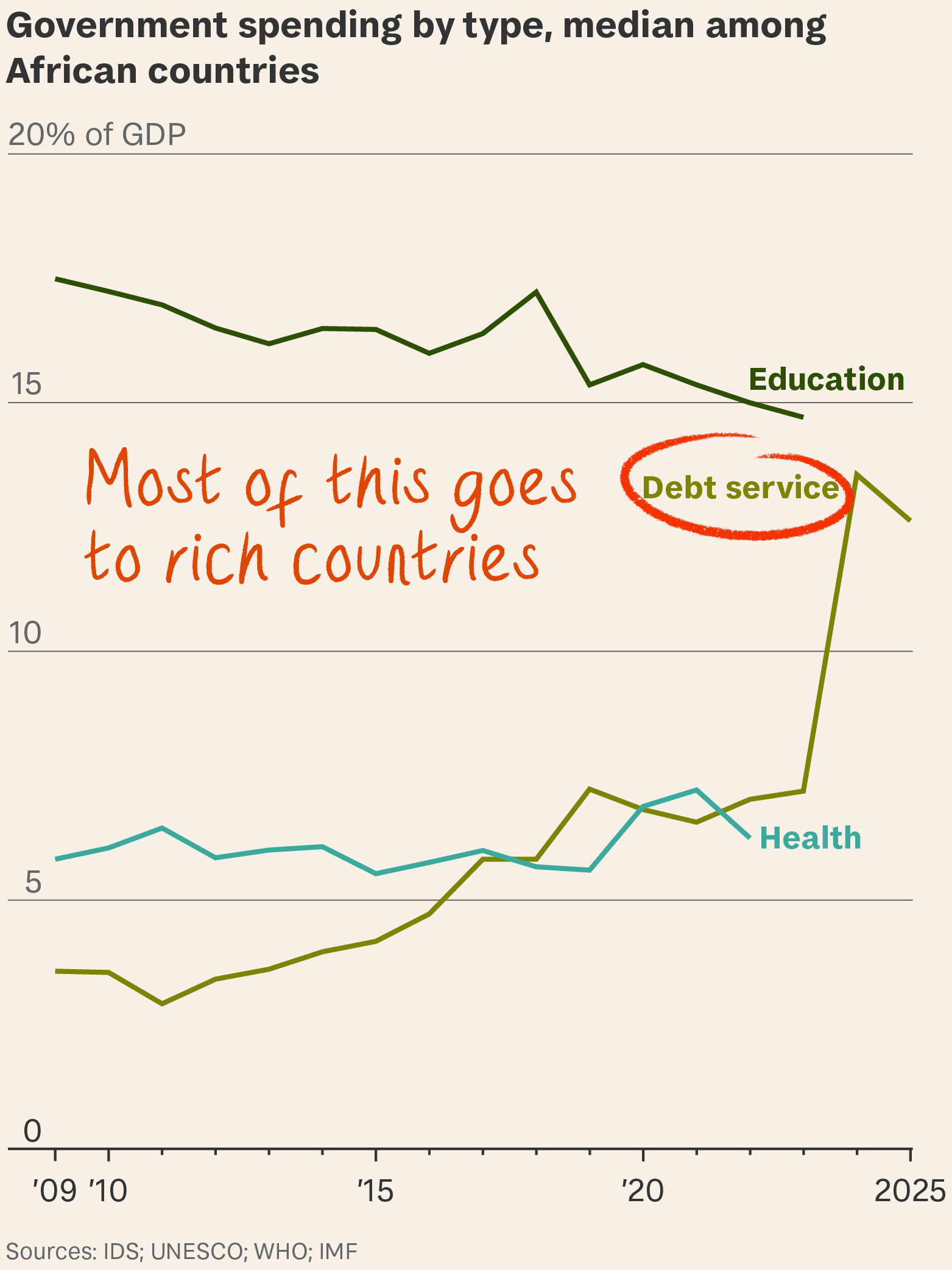

So what? Africa is already in a debt crisis. Thirty-two of its 54 countries spend more on interest payments than health, and 25 spend more on debt than education. Last year, former prime minister Gordon Brown called restructuring debt payments “a matter of life and death”.

Now that Trump has halted nearly all US aid spending, alongside cuts by the UK, France and Germany, it is even more urgent.

- In 2023, when aid was at an all-time high, Africa already sent more money to the rich world in debt repayments ($68.7 billion) than it got in aid ($59.7 billion).

- Africa’s interest payments are expected to reach nearly $90 billion this year, even as the amount of aid it receives is set to tumble.

- These repayments eat up government revenue that could be spent on hospitals, schools, roads and other infrastructure.

What happened? Before the pandemic, African countries spent less on debt. But when Covid struck, many borrowed to fund imports and keep government services going.

The continent’s debt-to-GDP ratio jumped from 31 per cent in 2010 to 67 per cent in 2023. This was a steep rise, but in line with the amount of extra debt taken on by rich countries.

The key difference. Whereas wealthy countries can take out loans at around 2 or 3 per cent, African governments, seen as high-risk borrowers, face rates as high as 10 per cent.

Crunch. Some countries are particularly hard-hit.

- South Sudan, the world’s poorest country with a life expectancy of 55.5 years, spends ten times more on debt payments than on healthcare.

- Malawi, where only 15 per cent of children finish secondary school, spends twice as much on interest as it does on schools.

- Debt repayments consume more than half of government revenues in Angola, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia.

By contrast, France spends 3 per cent of its revenues on servicing debt – despite having more of it in aggregate and as a share of GDP.

Bottom line. African companies also struggle to access the finance they need to grow, further hindering economic development. CEOs in Malawi and Zambia face rates of 33.5 and 24.5 per cent compared with just 1.4 per cent in Japan and 2.9 per cent in Switzerland.

This is going to hurt. Africa was the biggest recipient of US aid dollars, receiving $12 billion of $41 billion in 2024. The money went on everything from polio vaccines and paying nurses, to clean water and helping farmers endure droughts. Most of it has gone.

Aid groups warn the cuts will cost millions of lives. One possible solution? Forgiving debt.

We’ve been here before. A debt relief drive in the 2000s helped 37 countries – 31 of them in Africa – get more than $100 billion of debt forgiven. They spent much of this freed-up money on poverty reduction.

According to a recent study by the universities of St Andrews and Leicester, a new wave of debt relief that brought repayments down to 5 per cent of government revenue could

- give 33 million people access to basic sanitation;

- provide clean drinking water for 17 million people;

- help five million more children attend school; and

- save the lives of 60,000 children and mothers.

The catch. In the 2000s, most of Africa’s debt was owed to other governments or institutions like the World Bank. These days, most is held by private creditors. Debt justice campaigners accuse them of charging interest rates up to four times higher than the average and lending recklessly to crisis-hit African countries.

In 2020, the G20 launched a “Common Framework” to help debt-distressed countries restructure their payments, but private lenders with an eye on their margins have proved reluctant to engage.

What’s more… After lengthy talks, Ghana and Zambia got deals to reduce their debt repayments under the framework, but they are hardly transformative. Two-thirds of Zambia’s budget will still go on debt repayments until 2026.