On the day he sent troops into southern Lebanon, Israel’s prime minister also addressed the people of Iran from behind his desk. “There is nowhere in the Middle East Israel cannot reach,” Benjamin Netanyahu said. “With every passing moment the regime is bringing you, the noble Persian people, closer to the abyss.”

So what? It was equal parts wishful thinking and clear-eyed analysis.

- Iran’s economy is on its knees because of nuclear sanctions.

- Its regime is loathed except by those with an interest in its survival.

- The central planks of its foreign policy – regional dominance and the destruction of Israel – lie splintered in the rubble of southern Beirut.

- But Netanyahu’s warnings are more likely to unite Iranians against him than against their own theocracy.

Iran’s Supreme Leader is in a tough spot even so.

Khamenei’s trilemma. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei embodies a regime under siege from the triple threat of financial insolvency, political uncertainty and social instability.

The economy. Since President Trump scrapped the Iran nuclear deal in 2018 sanctions have been reimposed and Iranians have felt the consequences:

- Inflation is at over 30 per cent (it hit 64 per cent last year).

- Real wages and living standards have fallen commensurately.

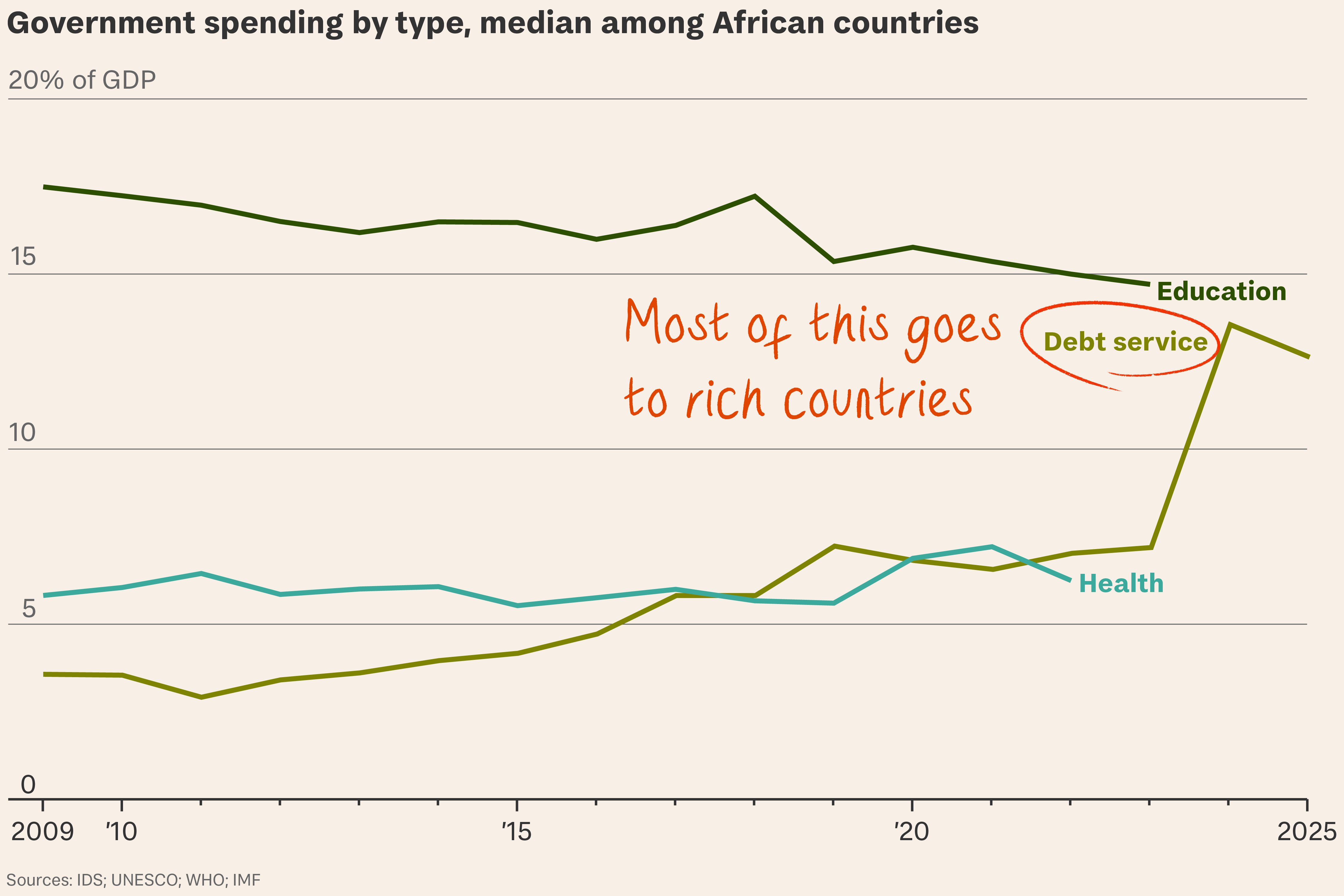

- The macro picture is of low state revenues, rising deficits, endemic corruption and slowing growth to which the government has responded with a deeply unpopular austerity programme, cutting healthcare funding and fuel subsidies.

- Sanctions-busting oil sales to China offer Tehran’s best hope, but they are at a steep discount to world prices of around $70 a barrel, and Iran needs $85 a barrel to break even.

Government. The new president, Masoud Peveshkian, is a moderate by Iranian standards but true power resides as ever with the Supreme Leader and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp (IRGC). Peveshkian’s efforts to re-engage with Europe and revive the nuclear deal have been derailed by geopolitics:

- Israel’s assassination of the Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran in July demanded at least the threat of retaliation.

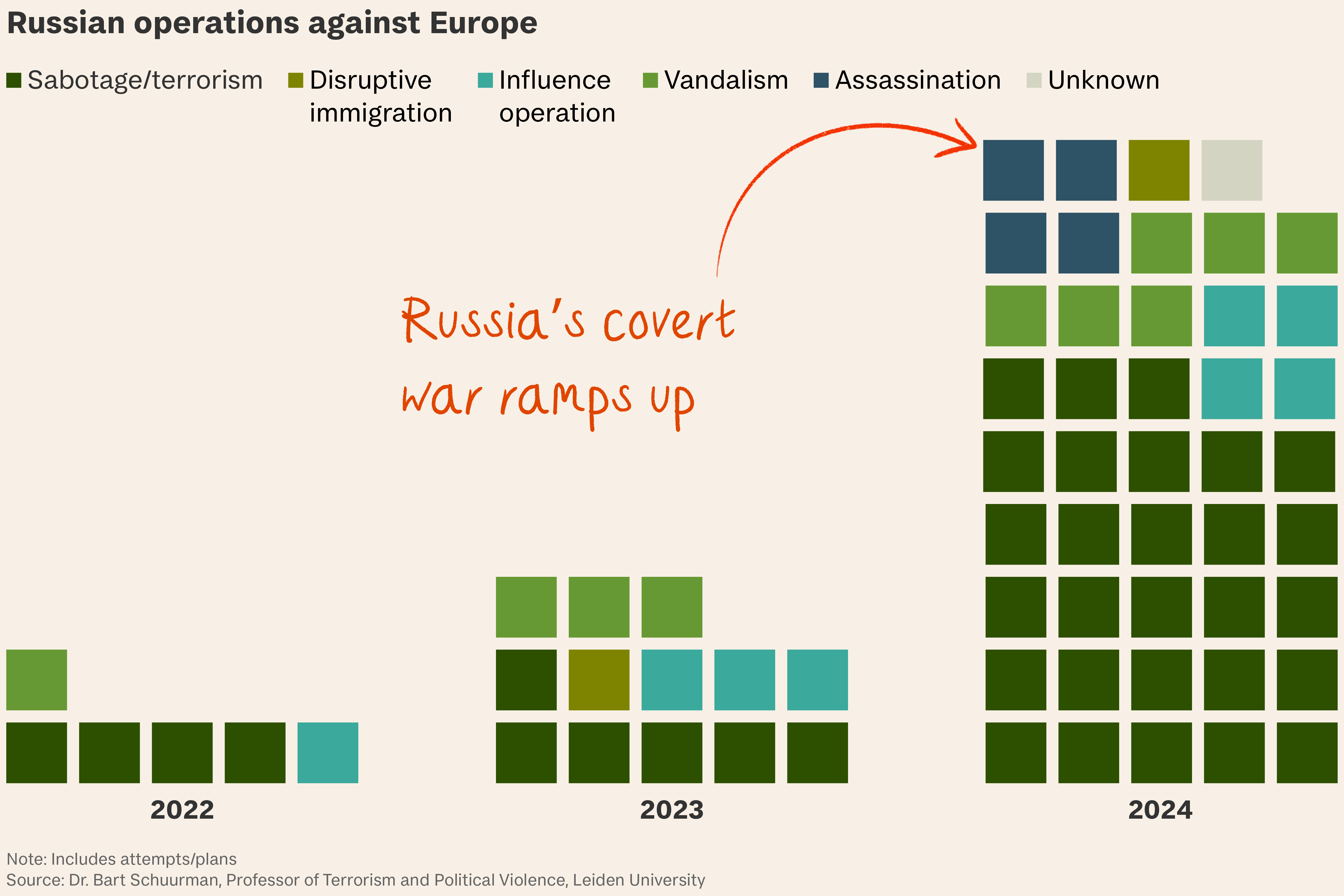

- Iran’s supply of drones to Russia for use in Ukraine has led to tighter, not looser, sanctions.

The mood. Sour. Nationwide anti-regime demonstrations following the death in custody of Mahsa Amini in 2022 for refusing to wear a veil have given way to large-scale “hardship” protests.

Iran’s options. It’s far from clear what, if any, action Iran will take against Israel. Options include:

- Direct strikes. The last time Iran bypassed its own proxies to attack Israel it launched more than 300 armed drones and missiles but 99 per cent of them were intercepted.

- Dishonest broker. Iran could enlist Russia to broker a ceasefire deal which spared the Islamic regime a public climbdown, but this looks implausible given Netanyahu’s intransigence on similar proposals for Gaza.

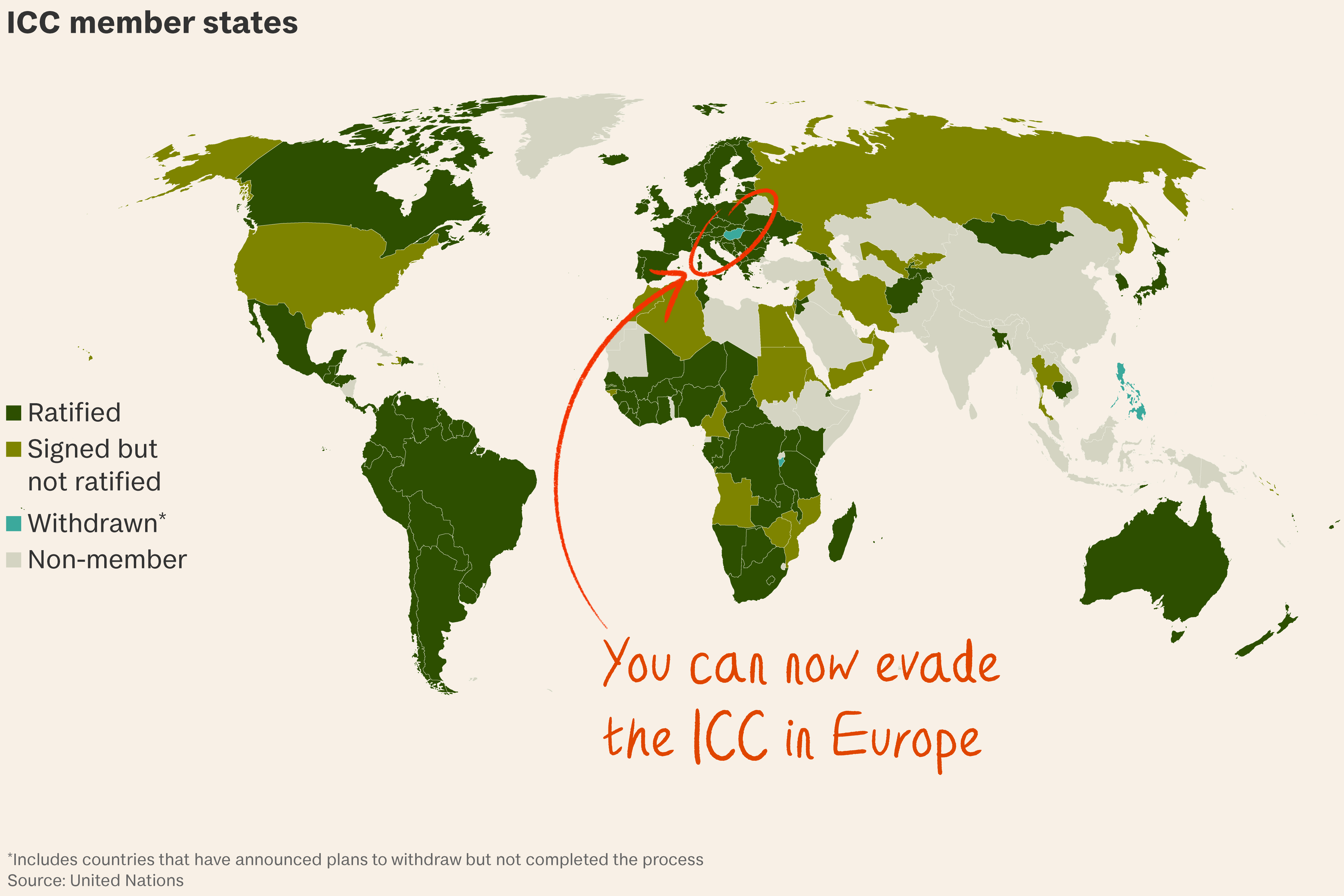

- Nuclear. US and Israeli intelligence briefings routinely suggest Iran is “weeks away” from acquiring nuclear weapons, but there’s no evidence it has them yet.

- Pure rhetoric. Khamenei could content himself with bellicose statements and no retaliatory action at all. But he knows that would risk his credibility, not only with his own hardline faction inside Iran, but across the region where Shiites and other Arabs feel outraged by Israel’s actions.

So far Iran seems to be going for pure rhetoric, though that could change with the news overnight of Israeli forces in “targeted” cross-border raids on southern Lebanon.

Succession. Khamenei is 85 and has had cancer. Whoever succeeds him will be chosen by a group of 88 elderly clerics. He (it will be a man) needs to be a canny CEO, a ruthless military leader and a pope-like religious authority all at once.

- The frontrunner. Khamenei’s eldest son, Mojtaba, acts as a chief of staff for his father and knows the ropes. He’s also a cleric with a black turban indicating he’s a direct descendant of the prophet Mohammed. He’s very private but likely to be on the extreme end of the ideological spectrum – he’s overseen the violent suppression of protestors and counts hardline clerics as his friends. But there’s a problem: handing power from father to son is too similar to the Shah’s reign – not a good look for the Islamic Republic.

- The insider. Less well known outside Iran is 65 year-old Alireza Arafi, a senior cleric whom Khamenei has been quietly promoting for 20 years. He’s an Ayatollah, so a higher-ranking cleric than Mojtaba. He also seems less extreme and more forward thinking, having spoken about how the seminary should embrace technology and AI to help advance Islamic civilisation.

There is a chance that there will be no new Supreme Leader if the IRGC decides it doesn’t want one. Its generals could stage a coup, turning Iran into another military dictatorship in the style of Egypt.

What’s more… One unlikely prospect is an uprising resulting in democracy. The opposition inside and outside Iran is, for now, too fractured.

To find out more about Iran’s succession drama listen to the Slow Newscast: The Hunt for the Next Supreme Leader