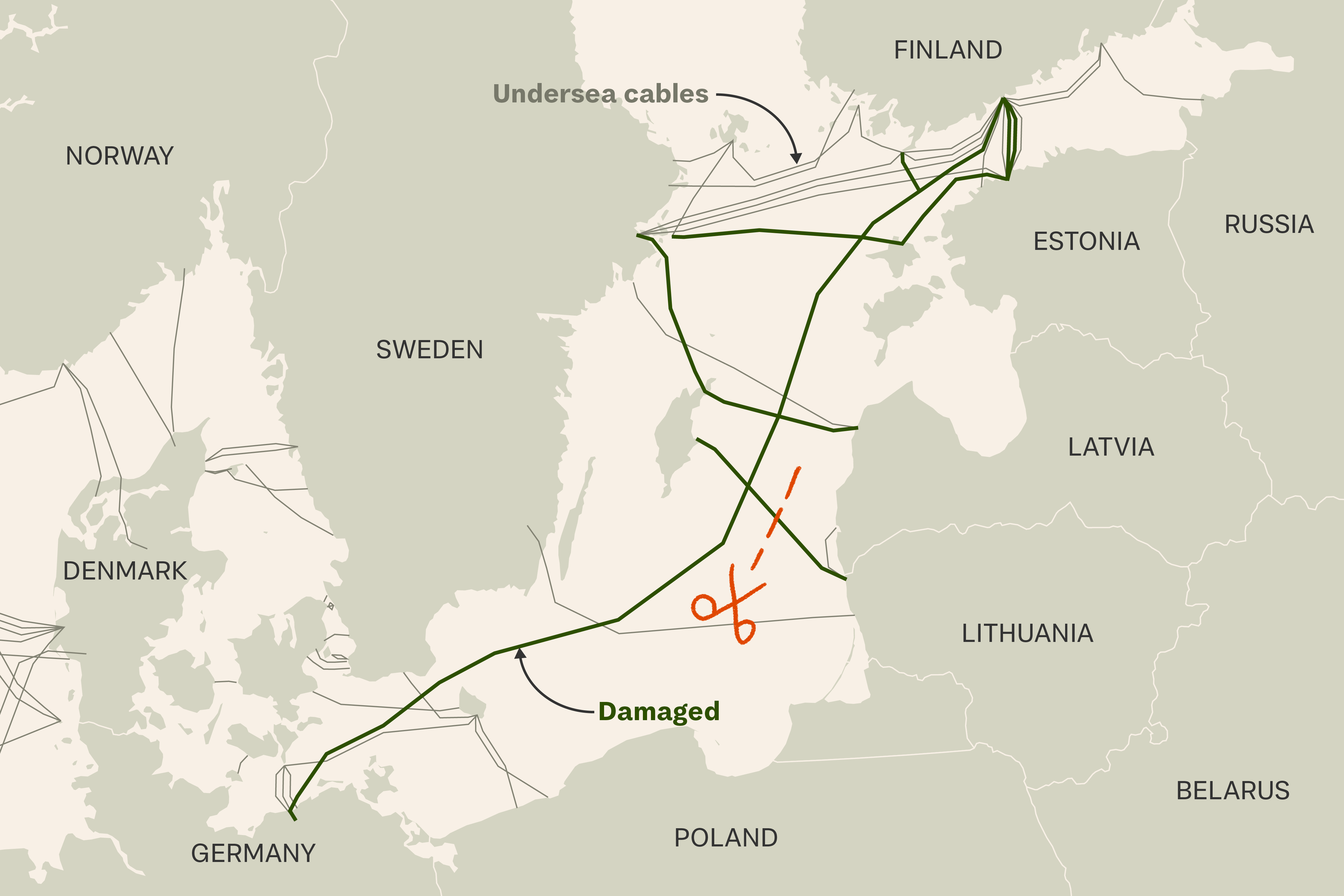

Russia is targeting undersea infrastructure. The Baltics are fighting back

Three days ago a Swedish SWAT team dropped from a helicopter onto a ship in the Baltic Sea between Latvia and the island of Gotland.

So what? Hours earlier, 50 metres below the surface, the ship had cut one of three main cables carrying data between Latvia and Sweden.

- This was the third cable-cutting incident in the Baltic in as many months, part of what experts suspect is an orchestrated campaign mounted by Russia against the Baltic states.

- Cutting isolated cables won’t break the internet, but it can disrupt finance, interrupt energy supplies and fuel tension in an age of hybrid war.

- It can also be a rehearsal for actual war.

Once bitten. Swedish authorities were criticised in November for allowing a vessel to sail on to Denmark after cables were damaged. On that occasion no investigators were permitted to board for a month; this time they acted decisively.

Baltic timeline

- 7 October 2023. NewNew Polar Bear, a Hong Kong-registered feeder vessel, was suspected of damaging the Baltic connector gas pipeline between Finland and Estonia and two fibre-optic cables, one between Finland and Estonia and another between Sweden and Estonia.

- 17-18 November 2024. Yi Peng 3, a China-registered bulk carrier, dragged its anchor along the seabed for 100km, damaging two fibre-optic cables, one between Finland and Germany and another between Sweden and Lithuania.

- 25 December 2024. Eagle S, an oil tanker registered in the Cook Islands, severed the Estlink 2 power cable between Finland and Estonia.

- 26 January 2025. Vezhen, a Malta-registered bulk carrier, severed a fibre-optic data cable between Gotland and Ventspils owned by the Latvian public service TV and radio channel LVRTC. Swedish police took control and are now investigating “suspected gross sabotage” in the port of Karlskrona.

What’s the damage? The incidents are a costly annoyance more than a serious disruption: 99 per cent of web traffic is carried by undersea cables but with 530 systems worldwide extending over 850,000 miles, it’s easily re-routed when one of them is cut.

LVRTC has detected a slight increase in latency, but no impact on internet speed. There has been a rise in Estonian power prices but no outages. Telecom cables can be repaired in weeks; power cables and gas pipelines in months.

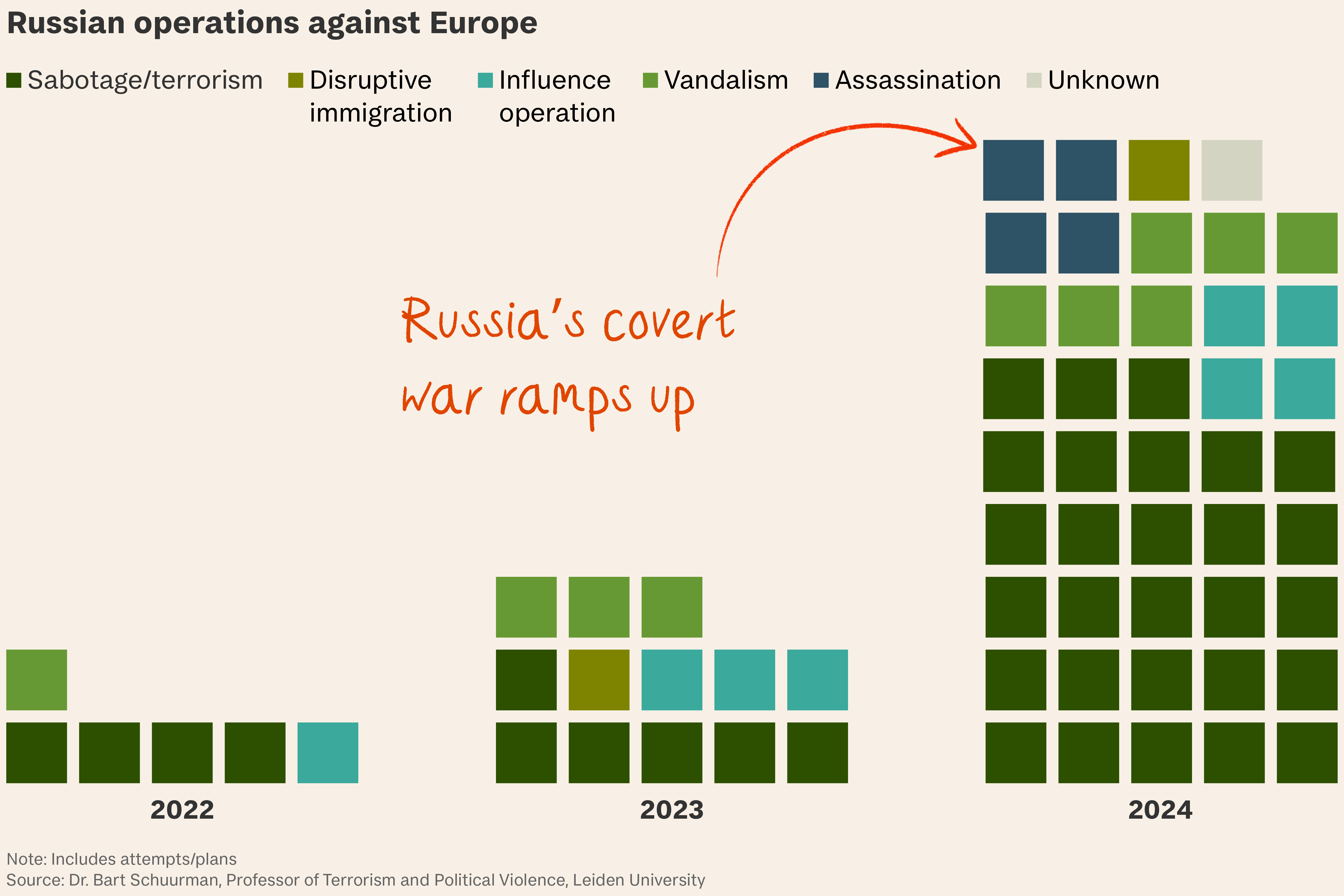

So what is Russia trying to do? Intimidate. The intention seems to be to erode public trust and generate fear while maintaining deniability. Severing Baltic telecoms cables while jamming GPS and mounting cyber attacks would also be an obvious wartime tactic.

The most recent incident is the biggest provocation yet, coming only 12 days after Nato launched a mission, Baltic Sentry, to prevent “damage to critical undersea infrastructure”. But it may also be the last.

What’s changed? Pushback. The Baltic states are learning fast. The Swedish reaction to the November incident was “half-hearted”, “almost a fiasco”, said Lieutenant Colonel Joakim Paasikivi, one of Sweden's leading defence experts.

This time they were prepared, storming the vessel with an armed police squad just as the Finns had done with Eagle S.

Will it work as a deterrent? It has certainly increased the costs. About a third of Russia’s oil exports pass through the Baltic, so any impediment to vessels in its “shadow fleet” is a drag on its wartime economy.

- Finnish police are still investigating the Eagle S for “aggravated sabotage” and expect to do so for months to come.

- The crew and owners of Vezhen can now expect similar treatment from the Swedes, so a previously low-cost method of harassing Nato’s Baltic members may now look less appealing.

- “When things don't succeed anymore, you change modus [operandi],” Paasikivi said. “The costs are increasing, so I would expect the Russians to do something else.”

That said… There’s plenty of undersea infrastructure less well-policed, and no shortage of bad actors who could take advantage. Exhibit 1: the Taiwan Strait.