Last week, Spain’s prime minister gave a speech championing migration as a way to protect prosperity and unveiling plans to integrate migrants into Spanish society.

So what? Almost no one else is saying this. Across Europe

- border checks are returning

- legal routes for migrants are narrowing

- illegal routes are being closed down and

- the politics of anti-immigration is gaining ground.

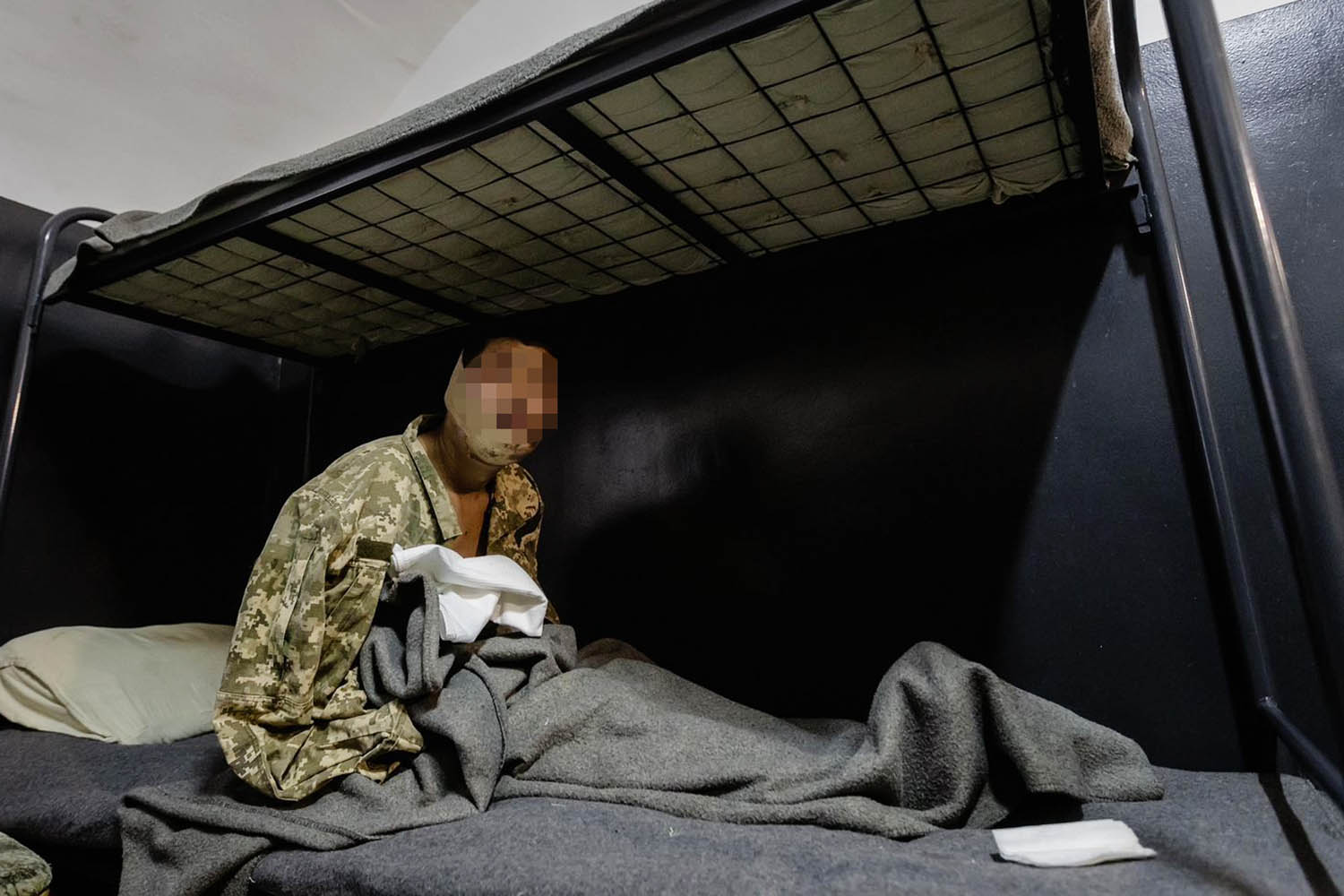

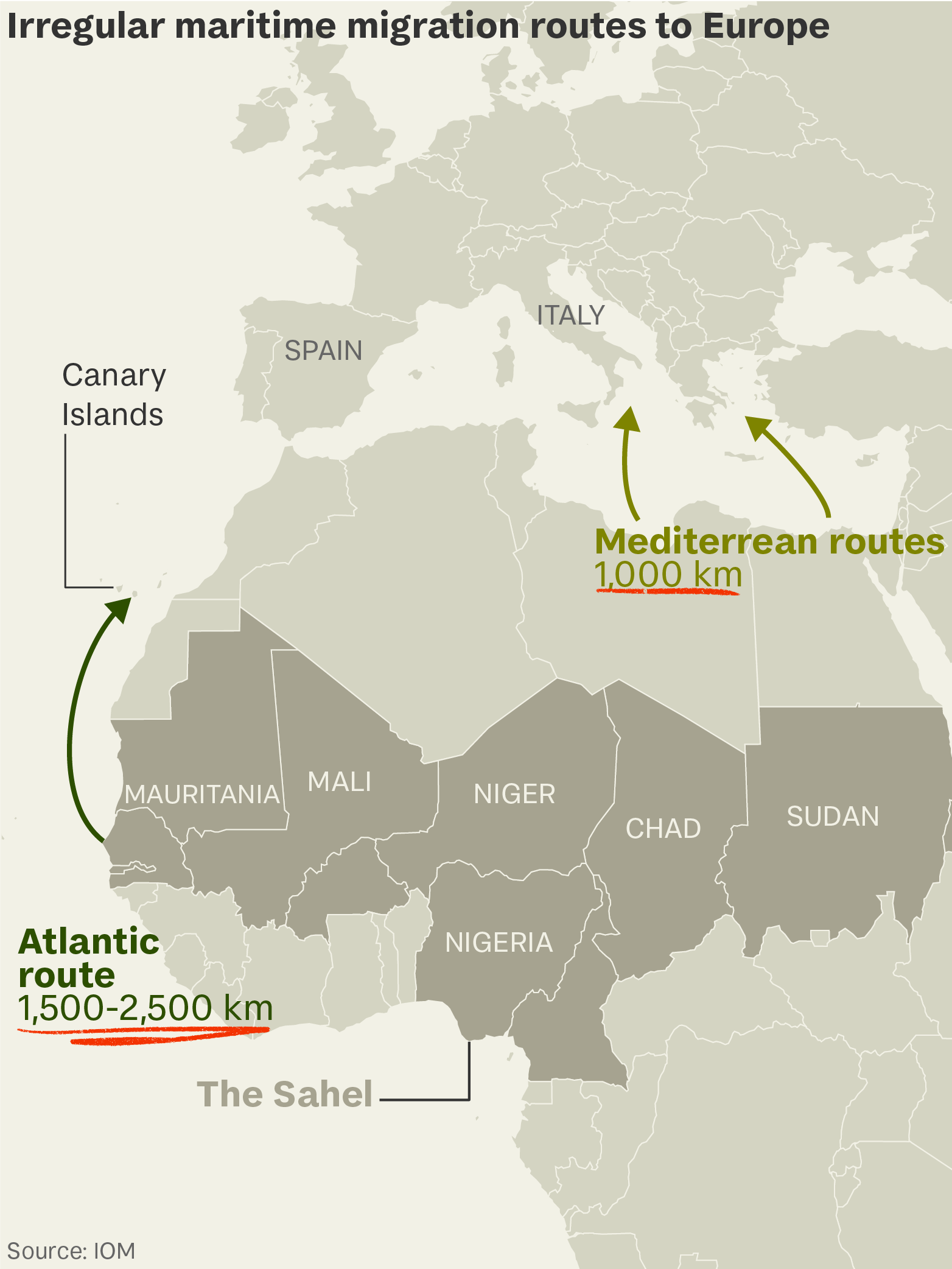

So why? Timing is key. Pedro Sánchez’s speech followed months of internal political clashes about how to manage a migrant influx to Spain’s Canary Islands via the arduous Atlantic route, weeks after El Hierro – the smallest of the islands – witnessed the deadliest migrant shipwreck in the archipelago in the past 30 years.

- The ocean route from West Africa to the Canaries is the most dangerous maritime route to Europe – a journey of up to 1,500 km through currents so strong that even coast guards and NGO ships leave the area largely unsupervised.

- Yet this is the only sea route to Europe that's grown busier in the past year, while migration across the Mediterranean has broadly declined.

- The main reason, aside from tighter border controls elsewhere in Europe, is increased violence in the Sahel, which in the past two years has become the world’s terrorism hotspot.

By the numbers:

26,758 – migrant arrivals in the Canary Islands via the Atlantic so far this year, up 85 per cent year-on-year

4,808 – migrants who died attempting the Atlantic route in the first five months of 2024 according to the NGO Caminando Fronteras – nearly 100 times more than have died trying to cross the English Channel (52)

37,970 – irregular migrant arrivals in Spain this year, up by nearly half on last year

“Six years ago, the migrant influx was focused on the mainland – Andalusia and Cartagena – but this year, almost 70 per cent of recorded arrivals through our activity on the ground have been in the Canary Islands,” says Íñigo Vila, emergency director at the Spanish Red Cross.

At the source. This year for the first time, Mali became the main country of origin for migrants entering Spain irregularly, followed by Senegal, says Frontex, the European border agency. Conflict is not new in the Sahel, but the number of violent events involving jihadist groups linked to Al Qaeda and the Islamic State has almost doubled since 2021.

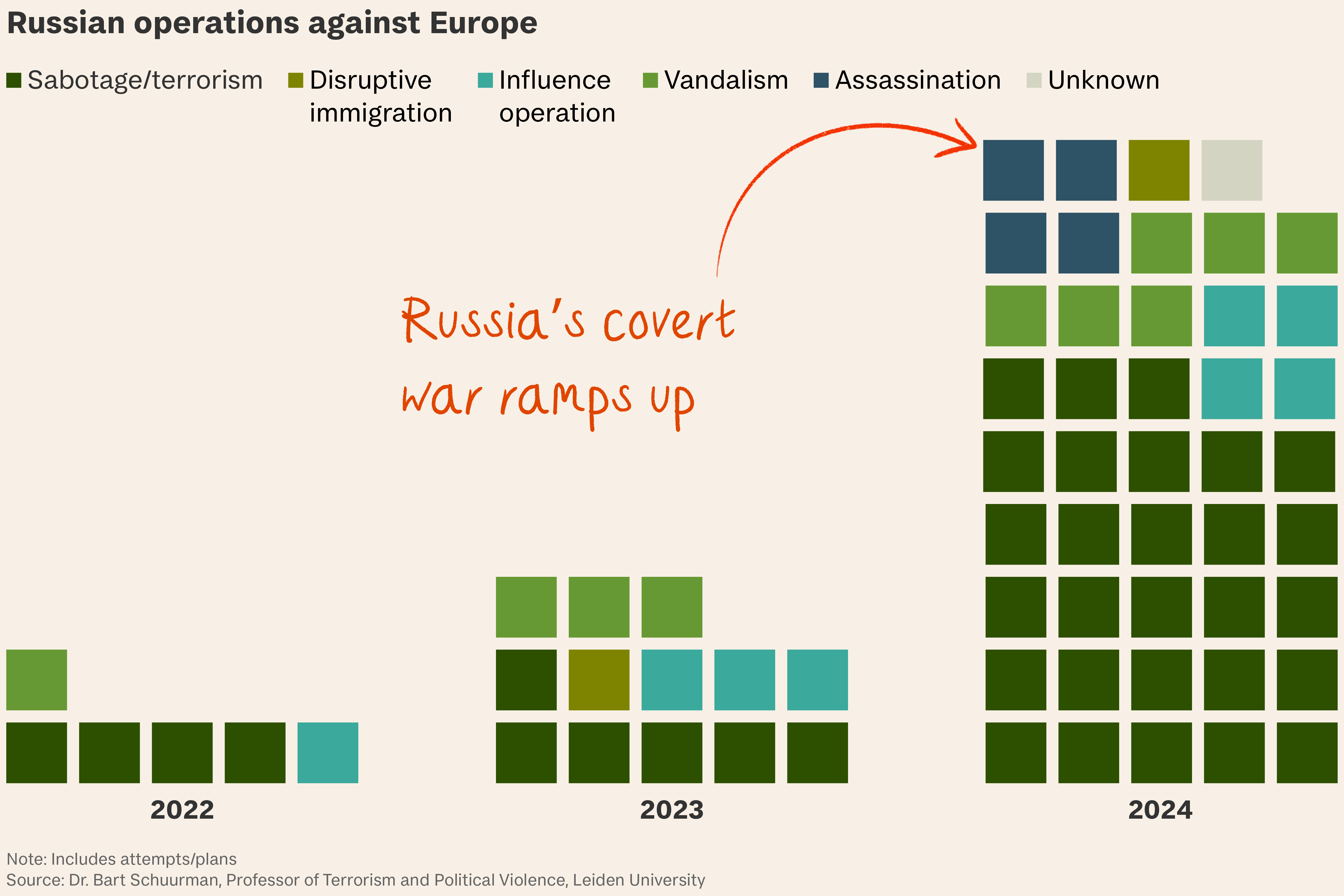

Terrorist groups are fighting for territory in a region that, according to Will Brown from the European Council on Foreign Relations, is becoming increasingly isolated after

- a wave of military coups in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger replaced western-backed governments; and

- new military juntas swapped French and American military assistance for Russian, mainly through the Wagner mercenary group.

The Wagner group now appears to be losing influence, but even so Brown calls the situation in the Sahel catastrophic: “Jihadist groups already control about half of Burkina Faso, a country the size of the UK, and Mali is not looking much better. That’s where asylum seekers are coming from.”

Against the tide. In his speech, Sánchez sought to confront surging anxiety about immigration, which has risen from ninth to first place in three months in a ranking of public concerns by a leading Spanish think tank.

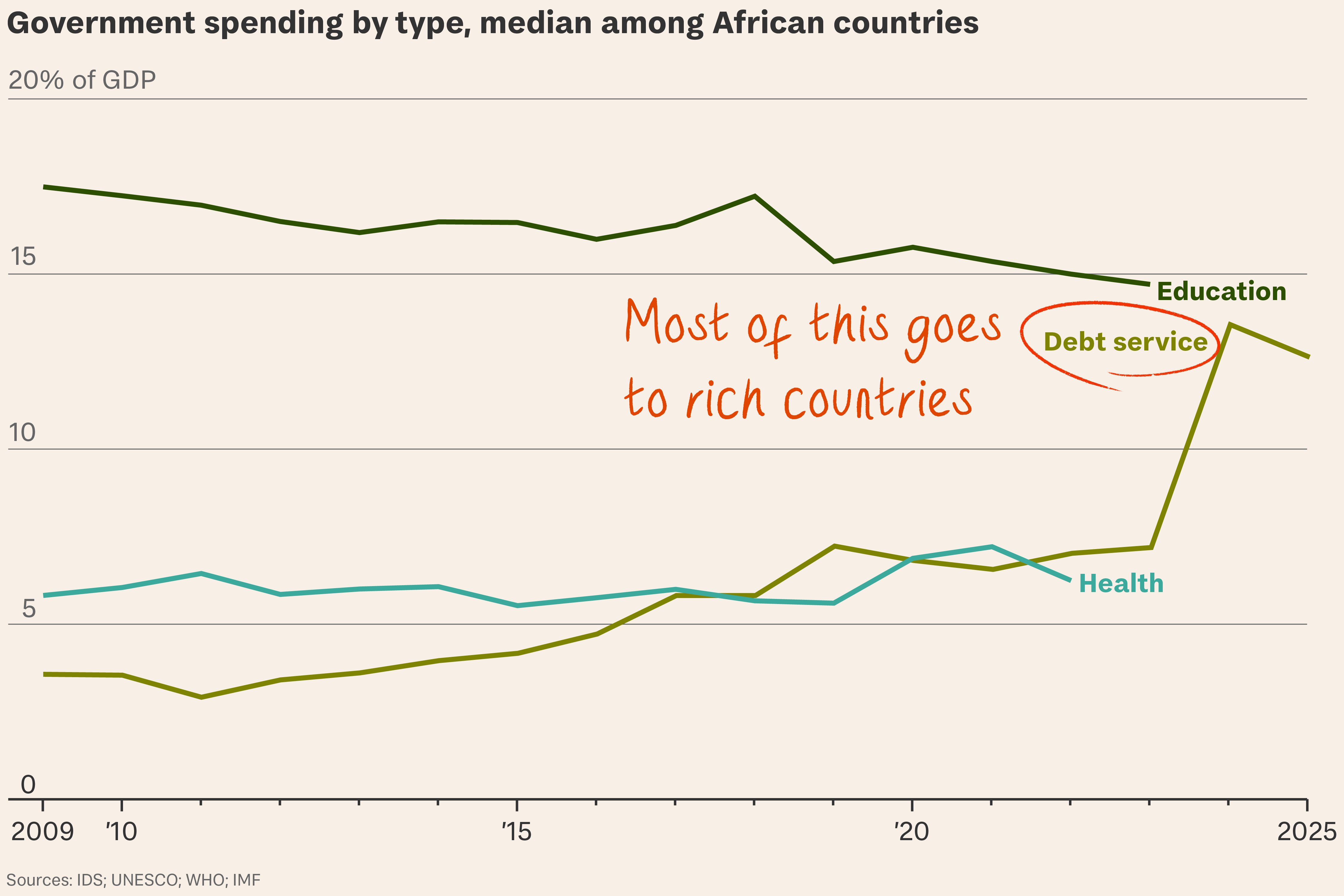

- Italy and the EU are paying countries in Africa to stop migrant crossings – a strategy that led to a two-thirds’ reduction in sea crossings this year, but has increased human rights violations at points of departure in North Africa.

- By contrast, Sánchez recently visited Gambia, Mauritania and Senegal and signed agreements to expand legal ‘circular’ migration. These agreements let asylum seekers undertake training programmes abroad leading to job offers with temporary work permits for up to four years, after which they commit to return to their country of origin.

Risk. This approach has been heavily criticised by Spanish opposition figures and could be impossible for Sánchez to sustain within his own fragile coalition.

Reward. But it is undoubtedly more humane than the alternatives, and in the long run could prove more effective. In May, the OECD cited Spain as an example of how high rates of migration helped boost economic growth by plugging gaps in the labour market.

What’s more… It’s one the UK could learn from, instead of looking to Italy.