On Monday, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán told his country’s parliament that “just as we were right about migration, we’ll be proven right about the war [in Ukraine]”.

So what? Context is everything. The success of Austria’s Freedom Party (FPO) in elections at the weekend puts another anti-migrant, Russia-friendly, eurosceptic party within touching distance of government.

Fortress Austria. The FPO finished first in parliamentary elections on Sunday, winning 29 per cent of the vote – its best result ever and nearly doubling its vote share since 2019.

The results “couldn’t have been clearer”, said leader Herbert Kickl, insisting his party should lead the next government. That’s far from certain:

- The FPO, which was founded by former Nazis in the 1950s, has been in coalition before as a junior partner in 2000, 2003 and 2017.

- But the governing centre-right People’s Party (ÖVP), which came second in this round, says it will not join forces with the FPO under Kickl.

- The ÖVP could instead form a government with the third-placed Social Democrats and a smaller party like the liberal Neos, blocking the far-right from power.

Kickl, who has aligned himself closely with Orbán, promised during the campaign to build a “Fortress Austria” to keep out migrants, and said this summer that he and Orbán backed a “peaceful solution” to the war in Ukraine. He has styled himself as “Volkskanzler”, or People’s Chancellor, a term associated with Adolf Hitler.

Kickl’s highest levels of support, says Misha Glenny, rector of the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, are among 18-34 year-olds. “When you get up into the older age ranges, their support for traditional parties is much higher,” he said. The FPO is much more effective on social media, with 216,000 YouTube subscribers against the 1,500 commanded by the ÖVP, and has more followers on Facebook, Instagram and TikTok.

Even if the FPO doesn’t end up dominating (or even participating) in the Austrian government, it could still impact European politics, says Catherine De Vries, a political science professor at Bocconi University.

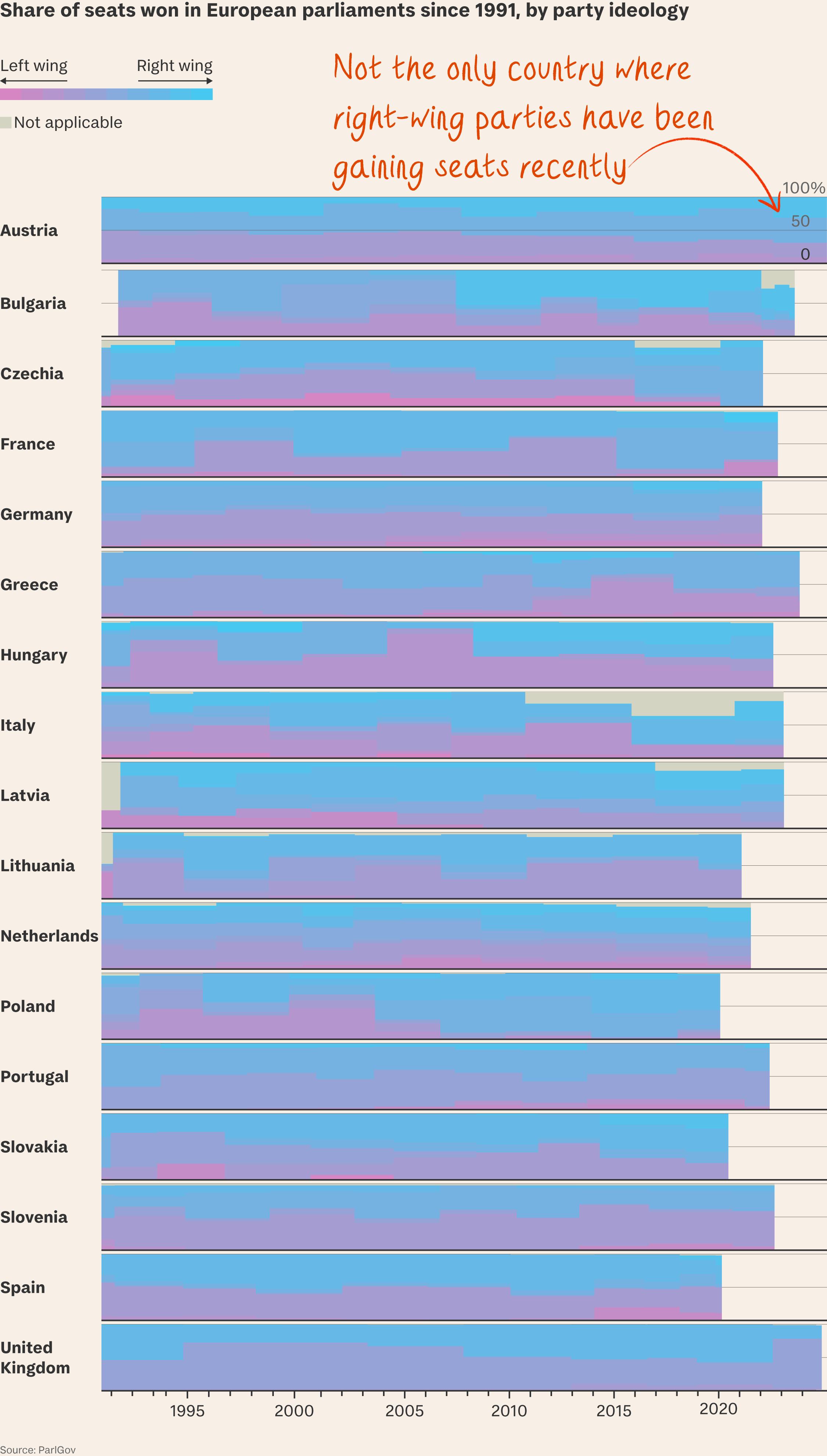

- Austria’s results fit a trend of far-right wins in other national elections in Europe: Geert Wilders’ populist party won Dutch elections last year, and Giorgia Meloni is leading Italy’s most far-right government since the Second World War.

- In Germany, the far-right AfD won a regional election last month in Thuringia. France’s National Rally came first in European parliament elections in June and won a record number of seats in France’s parliament in national elections.

- If the Czech nationalist Andrej Babiš wins elections next year, that could create a bloc of states with an “Orban-esque” vision of the EU, spanning the four countries that once formed the core of the Austro-Hungarian empire. That vision, says the Eurasia Group’s Mujtaba Rahman, puts at risk any EU council action that depends on unanimity, including support for Ukraine.

Unity project. It’s worth remembering that none of the far-right’s recent gains stopped Ursula von der Leyen securing a second term leading the European Commission, where the top jobs have gone to “the grand coalition, Conservatives, Socialists and Liberals,” says De Vries. “In addition, the far-right groups in the European Parliament often don’t cooperate.”

But… neither national governments nor the EU have good answers about how to respond to the appeal of right-wing populism.

- In 2000, when the FPO was poised to enter government for the first time, the EU was so outraged that it announced diplomatic sanctions even before the coalition was formed. That “blew up in the EU’s face,” says Glenny; it was seen as anti-democratic and ultimately proved largely symbolic. It’s one of the reasons why the EU remains reluctant to sanction member states.

- Instead, governments are trying to address voters’ concerns by tightening migration policies: Germany has announced border checks; French PM Michel Barnier laid out plans yesterday for stricter immigration policies in a keynote speech to parliament.

Voters are also worried about living costs, healthcare waiting lists and housing shortages, which far-right parties link to migration. Mainstream parties haven’t developed an alternative narrative to address these concerns, De Vries argues.

What’s more. A Trump win in the US presidential election in November would likely encourage the populists. When Hungary took over the rotating EU presidency in July, Orbán’s slogan was: “Make Europe Great Again”.