Europe needs a workable migration strategy. Instead it’s attacking asylum seekers to placate the right.

Last week, an Italian charity that saves migrants at sea said a Libyan coast guard patrol fired on its rescue vessel in what it called a “wicked intervention”. On 1 April, 74 migrants were rescued off Gavdos, a tiny Greek island which has seen a steep rise in migrant arrivals this year but has no processing facilities.

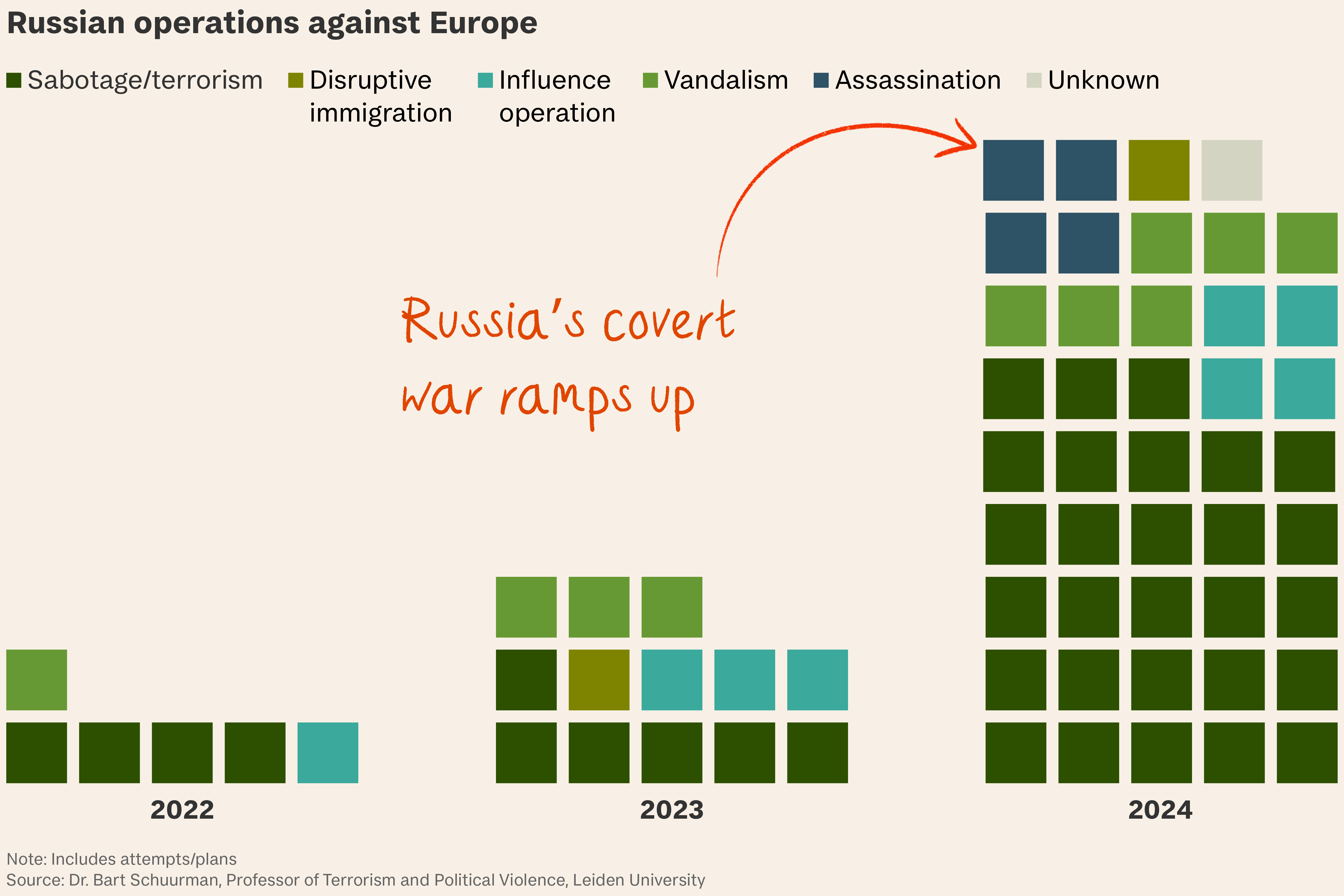

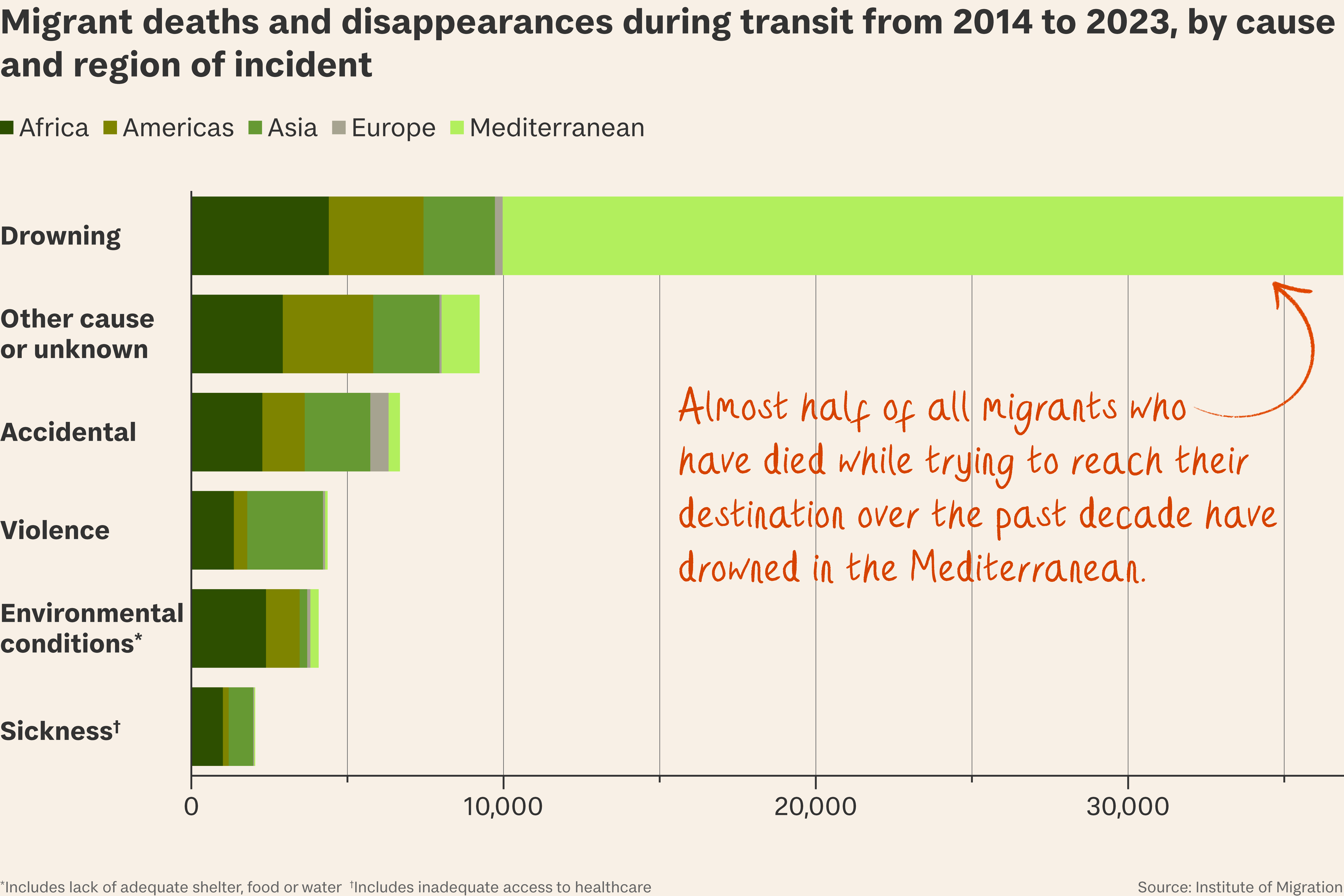

So what? Nearly a decade after a surge in migration caused by the Syrian war, migration remains a burning political issue across the EU. Like the UK, the bloc is attempting to “stop the boats” ahead of looming elections, but irregular migration numbers are rising again – and so are deaths.

By the numbers:

293,000 – undocumented arrivals in the EU in 2023, the highest since 2020, according to the International Organisation for Migration

3,015 – estimated deaths in the Mediterranean in 2023, up 29 per cent year-on-year

€16.9 billion – Tortoise estimate of EU funding for refugees and migration outside the EU since 2015

The goal. The EU has not been sitting idle. In the past year, the union and its members have tightened external borders and asylum laws and struck deals with neighbouring countries to stop migrants crossing and to outsource asylum application processing.

New laws including a set of measures due to be adopted this week that allow stricter asylum procedures and facilitate detention and deportations.

New deals include agreements with

- Tunisia, €158 million;

- Mauritania, €210 million;

- Egypt, €7.4 billion, with at least €200 million set aside for migration;

- the UK, to share intelligence with EU border protection agency Frontex; and

- Albania, which by agreement with Italy will host two holding facilities for migrants rescued in the Mediterranean, due to be operational in May.

Hardening immigration lines among political parties across the EU – led by Italy, Germany, France and the Netherlands – have been gaining traction since the 2015 surge in asylum seekers fleeing to Europe from Syria, but have had minimal effects on reducing irregular migration.

The cost. Human rights advocates say that:

- more migrants are dying or going missing as they take more dangerous routes; and

- more autocratic regimes are committing human rights abuses using EU funds with no oversight.

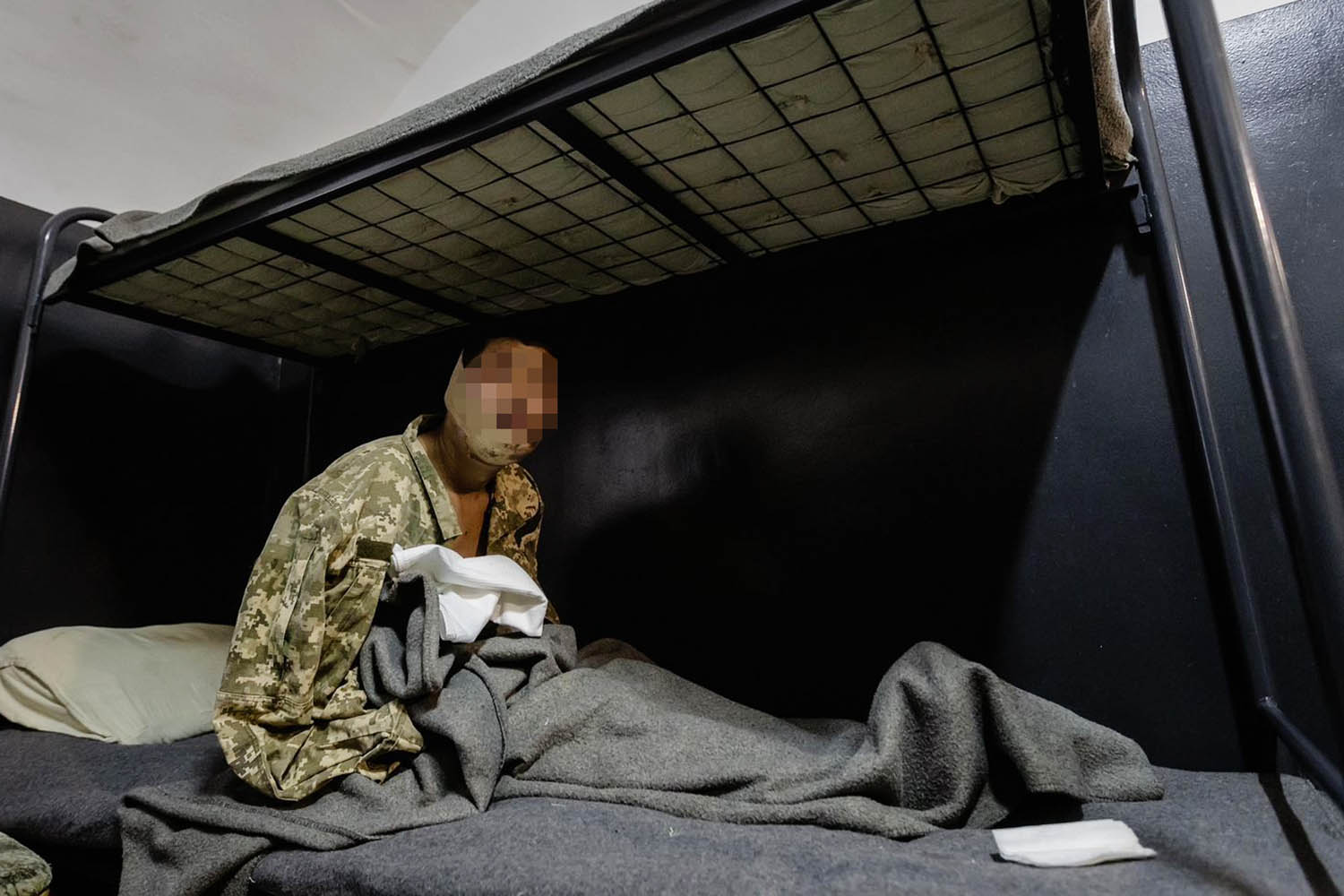

A recent UN investigation found that the bloc’s support for Libyan security forces since 2017 (incluing a €57 million payment) has made the EU complicit in abuses towards migrants and refugees – including torture, rape and arbitrary detentions – that “may amount to crimes against humanity”. Similar concerns exist for Tunisia and Egypt.

Decision time. EU parliamentary elections are due in June. Irregular migration is likely to pick up in the interim as warmer temperatures encourage more crossing attempts, driven by ongoing conflicts outside the EU and labour shortages inside the EU.

“Our concern,” says Meghan Benton of the Migration Policy Institute, “is that with the rise of the far right we’ll end up with a lot of governments that only focus on border enforcement.”

A healthier debate, according to Eve Geddie of Amnesty International’s EU office, should be based on the evidence – most people arrive in the EU with a regular visa – and the political courage to face the mismatch between the investment and attention given to migration as a policy domain in the past 20 years and the unsuccessful outcomes.

The EU claims to be committed to “protecting asylum, protecting the borders and fighting or combating irregular migration”. In reality its migration strategy is based on fighting asylum seekers. It’s the wrong strategy, and not just because it isn’t working.

More than 70 countries are holding elections this year, but much of the voting will be neither free nor fair. To track Tortoise’s election coverage, go to the Democracy 2024 page on the Tortoise website.