Seoul is arming Europe in the face of Russian aggression, and deterring China from trying something similar.

Last week, brightly coloured umbrellas lined Seoul’s rainy streets as people waited for South Korea’s first military parade in a decade.

So what? A lot has changed since the last parade in 2013. A war in Europe is changing the shape of an economy halfway around the world: South Korea has quietly become a military-industrial juggernaut, matching or eclipsing many of the old arms-dealing nations with hardware that has become a central part of the US strategy to support Ukraine against Russia.

- South Korea’s arms exports more than doubled to $17 billion in 2022, making it the ninth-biggest weapons seller in the world.

- Former President Moon Jae-in has called the defence sector an “economic lifeline”; promoting it abroad has also become a central plank of South Korean diplomacy.

- Moon’s successor plans to make South Korea the world’s fourth-largest arms exporter by 2027.

K-Pop or K-boom? If one deal exemplifies the surge, it’s a $13.7 billion contract Seoul signed with Warsaw last year which will recast EU security, making Poland the most capable army in Europe, at least on paper. The deal includes:

- 1,000 K2 tanks, giving Poland more tanks than the UK, Italy, Germany and France combined.

- Nearly 700 K9 self-propelled howitzers, which can shoot Nato-standard shells about 30 kilometres (the UK has 110 similar artillery pieces).

- 48 Fa-50 fourth-generation jets modelled on the US F-16, which Zelensky has been seeking since Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Chinese incentive. As the Indo-Pacific rearms in the face of runaway Chinese military spending (estimated by the US government to be around $700 billion a year), the rest of the region is also looking to South Korea as a weapons designer and supplier.

- Indonesia has built South Korean-designed amphibious vessels.

- Vietnam and the Philippines are interested in modernising their arsenals.

- South Korea is licensing designs for its best-selling K-9 howitzers to India, Egypt and Australia among others.

Further afield, the United Arab Emirates is paying more than $3.5 billion for the Cheongung air defence system, which protects Seoul’s skies against the ever-present threat of missiles from the North.

American dream. The roots of South Korea’s success can be traced back to the 1980s when Washington licensed Seoul to build US weapon systems like the F-16.

“Essentially, they’ve gone through a process of importing foreign designs, building those designs, modernising those designs, and now producing entirely indigenous designs,” says Tom Waldwyn of the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

While America’s defence industry has focused on often dizzyingly complex new weapons systems, South Korea has specialised in mid-level weapons like artillery and tanks, which suddenly became much more desirable when Russian tanks rolled towards Kyiv.

“They have to prepare for conventional war,” says Waldwyn. “Unlike Europe, they have hot production lines, which means they can build orders very quickly and deliver them at speed and a high level of quality.”

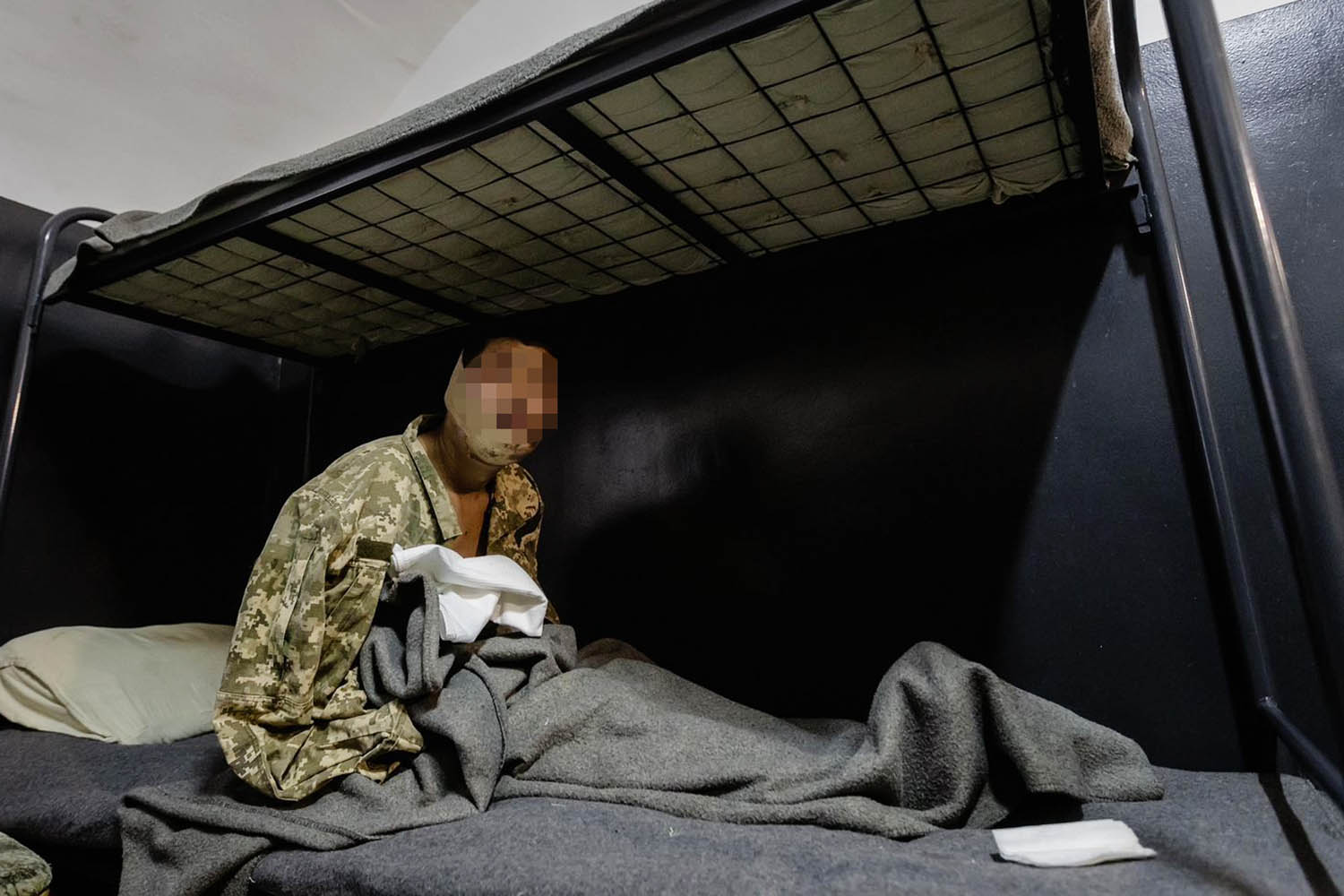

Ukrainian tightrope. South Korea has so far refused to send armaments directly to Kyiv. This is partly out of reluctance to openly antagonise Moscow, which it hopes might cooperate against an increasingly cantankerous northern neighbour.

Instead, South Korea has walked a fine line, shipping half a million Nato-standard shells to the US to free up American arsenals for use in Eastern Europe.

UK pop too. Next month, South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol will head to the UK for a state visit. His foreign minister is already flattering the Conservatives, describing Britain as a “global power” and welcoming their decision to send a new aircraft carrier on a tour of the Far East.

South Korea is building its first carrier with British help; deals going the other way are likely as the UK tries to modernise its army on a budget. Where the KIA Sportage led, expect the K-9 howitzer to follow.