There’s a marketplace for international acceptance, and the desert kingdom can afford it.

This week Saudi Arabia secured the rights to host the 2034 men’s World Cup, confirmed a $52 million donation to help restore the Pompidou Centre in Paris and signed an extension to the UK’s deal to help build the Saudi tourism industry.

Last week Agence France-Presse reported that Saudi Arabia has executed 303 people so far in 2024 – the nation’s highest ever total, and the second highest worldwide for this year.

So what? Saudi Arabia is trying to modernise its society and economy – an essential project that other countries can and should be involved in. But while football does its best to play the ‘sport not politics’ card, the art world deals explicitly in politics.

Until 2020, the arts were effectively outlawed in Saudi Arabia. Music, cinemas and theatres were banned. Before 2023, onstage kissing was banned. As 2024 draws to a close and Riyadh pays billions for an accelerated cultural mash-up with the world, the line between cooperation and complicity is, to put it delicately, blurred.

That was then, this is now: this year alone, the kingdom has

- agreed a deal with the UK for Historic England to help restore cultural landmarks.

- hosted a fundraising visit from the National Theatre, Edinburgh International Festival, Royal Ballet and Opera, South Bank Centre and Cameron Mackintosh Theatres.

- issued licences to Sotheby’s and Christie’s to open auction houses in Riyadh.

- signed a two-year collaboration agreement with the King’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts, starting with Saudi Arabia’s Year of Handicrafts 2025.

- agreed a deal with the Science Museum to create a museum hub in Riyadh.

If you book them, they will come. In 2024 the kingdom hosted its first Chinese contemporary art exhibition, a touring immersive Monet exhibition, and Alicia Keys and Pharrell Williams at an International Women’s Day event. It has welcomed Olivia Wilde, Michael Mann, Dev Patel, Jeremy Renner, Marisa Tomei and Andrew Garfield, and in December it booked Spike Lee to head the jury at next year’s Red Sea Film Festival.

Why is Saudi Arabia doing this? To diversify its economy away from oil. Giga-projects at the heart of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 scheme include

- Neom, a futuristic megacity in the northwest;

- a Red Sea luxury tourism destination; and

- a metro system in Riyadh.

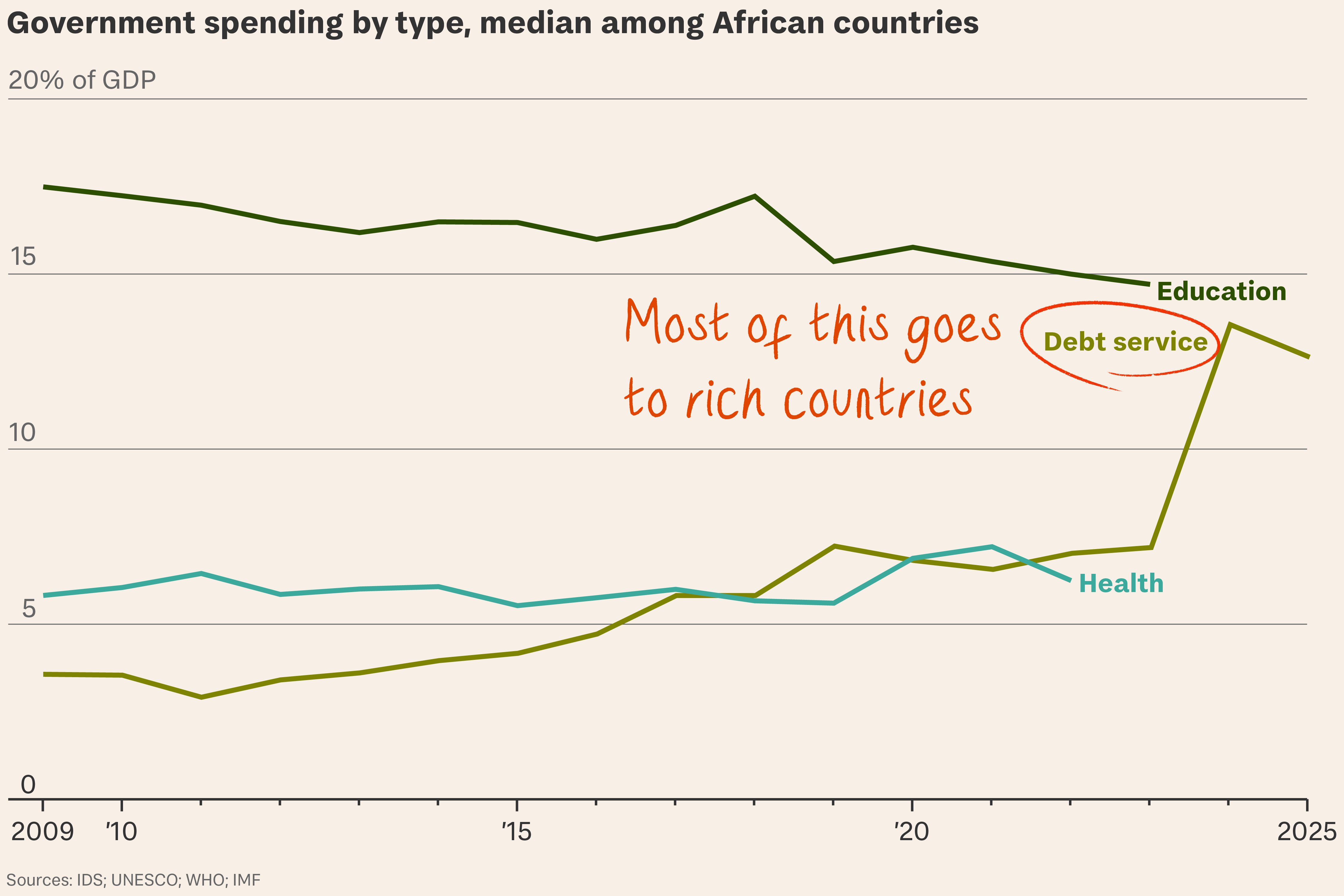

Why is the British arts world doing this? Funding for the arts is plummeting in the UK. Between 2009 and 2023, local government support has fallen by 48 per cent. The Department for Culture, Media and Sport has cut core funding of cultural organisations by 18 per cent and Arts Council England has seen its funding reduced by 18 per cent, according to research from the University of Warwick. In 2023, commercial sponsorship fell for the fourth year in a row. Martin Prendergast of the European Sponsorship AssociationProtests says protests this year over arts sponsorship by Baillie Gifford and Barclays are alienating commercial funders further.

On the upside. In a short period, Saudi Arabia has abolished its religious police, allowed women to drive, ditched segregated restaurants and abolished male guardianship laws that required male consent for women to work or travel abroad.

And yet. In 2023, 50 members of the Howeitat tribe, who currently live on the proposed site for Neom, were arrested for resisting eviction. In May 2024, a dissident Saudi intelligence officer, Colonel Rabih Alenezi, told the BBC police had been authorised to kill protesters.

Will this art ne’er be clean? The history of arts funding is steeped in politics, cruelty, violence and reputational laundering. When Shell’s publicity director, Jack Beddington, proposed arts sponsorship in 1934, he was following in a tradition that can be traced back through the robber barons of America’s Gilded Age (and New York’s Museum of Modern Art), the Medici family (funding the Renaissance while bribing and murdering their way to power in Florence) and the crowned heads of Europe, patronising artists while plundering their colonies.

Not incidentally... exports to Saudi Arabia were worth £13.1 billion to Britain in 2023.