The former Conservative leader William Hague and the Labour peer Peter Mandelson have both warned this week that student tuition fees in the UK will have to rise.

So what? They’re probably right. British universities are in the middle of a slow-motion fiscal car crash as the new term starts:

- 40 per cent of UK universities are running unsustainable deficits, according to the Office for Students.

- 70 of the country’s nearly 290 higher education providers have announced restructures or redundancies, according to the University and College Union.

- One of six potential disasters drawn up by Sue Gray, Keir Starmer’s chief of staff, involves at least one university going bust.

- Huddersfield, York, Coventry and Kent currently report severe deficits.

Students. Who cares? With staffing and funding crises in primary education, prisons and the NHS, higher education is not a government priority. But the sector provides around 315,000 jobs including 150,000 in academia. It contributed £265 billion to the economy in the 2021–22 academic year – around 8.6 per cent of GDP, which is more than mining, agriculture, forestry, fishing and defence combined.

Moreover, the UK’s Russell Group universities continue to outperform rivals in every other rich country apart from the US despite the squeeze.

Not like this. In 1998, the Labour government introduced tuition fees of £1,000 per year to fund an increase in the number of university places. A series of tinkering interventions since then has served mainly to make things worse.

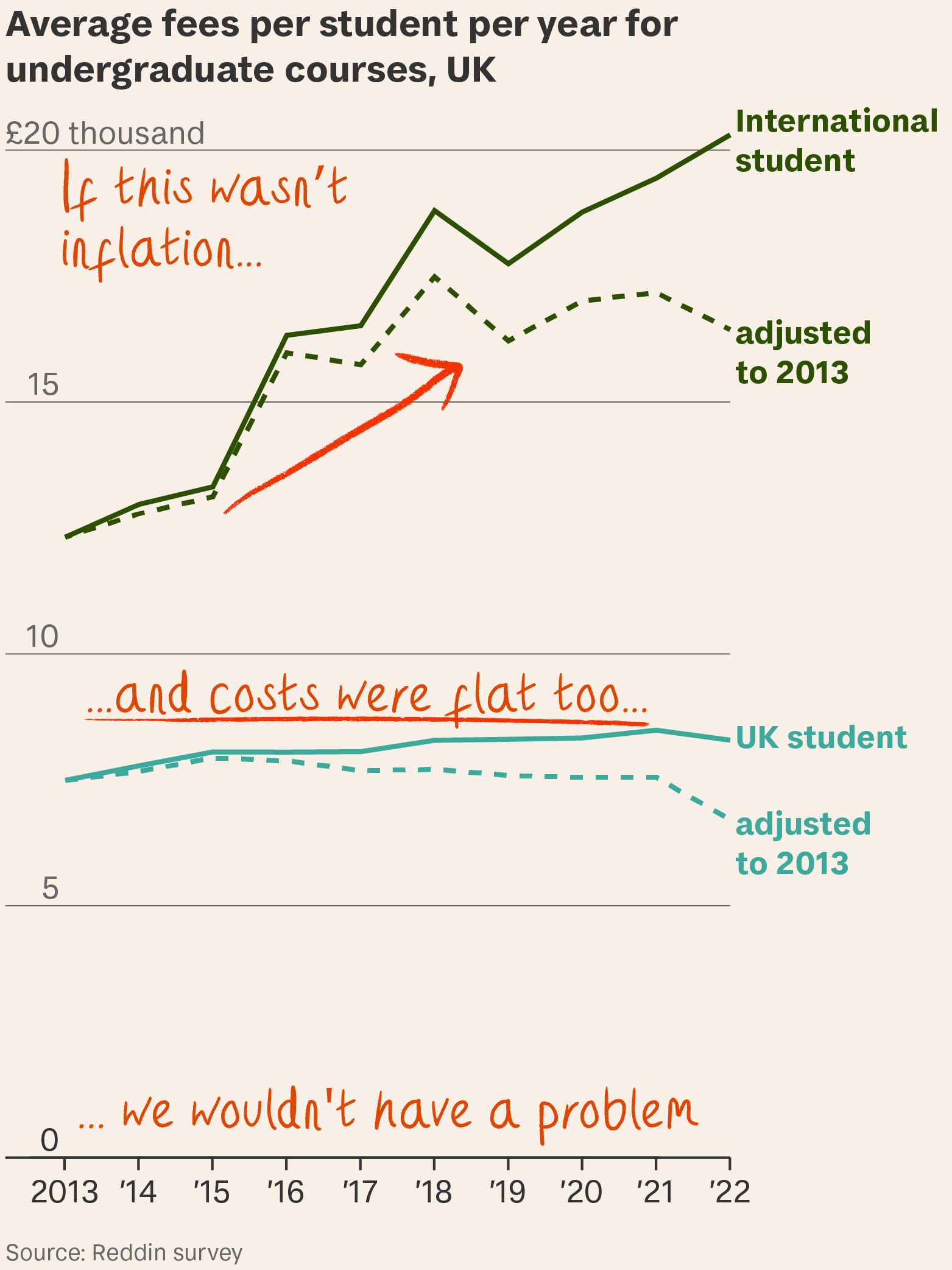

- 2012: as the number of school-leavers going to university peaked, the government raised the fees cap from £3,000 to £9,000 a year, then left it untouched until 2017 when it rose to £9,250. Inflation hit 11 per cent in 2022. The fees are currently worth £6,500 in 2012 prices.

- 2014: a cap on student numbers was removed. Top institutions boomed. Smaller ones suffered.

- 2016: Brexit meant fewer EU students and more reliance on uncapped overseas students’ fees, which can reach £67,000 a year for specialist courses like medicine.

- From 2023: students starting university will make loan repayments for 40 rather than 30 years, start repaying when their salary reaches £25,000 rather than nearly £30,000 under the previous system, and pay a higher rate of interest.

- 2024: restrictions on overseas students bringing dependents with them hit older postgrad students. The number of visas granted to Indian students fell by 23 per cent and to Nigerian students by almost half.

If you close it, they will leave: the former US senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan once said: “If you want to build a great city, create a university and wait 200 years.” The process also works in reverse.

First-year chemistry student numbers at the University of Hull fell from 160 in 2012 to fewer than 20 last year. The department will close this year. If the university closes too it could cost one of the most deprived parts of the UK 9,000 jobs and £694 million a year.

Sue Gray’s dilemma: What will the government do if a university runs out of money? How to put the sector on a firmer footing? The signs are the answer to the first will be – not much. Jacqui Smith, the minister for skills, has said “if it were necessary” the government would let a university go bust. As for the second, there are three main proposals offered by interested parties:

- Taxpayer funding. The government could increase the £1 billion annually it gives in grants to cover fees.

- A graduate tax. Good for the taxpayer; bad for guaranteed university income.

- Index linking fees. Currently the favourite of most commentators including Hague and Mandelson; vehemently opposed by the National Union of Students.

You’ll pay for this: Jo Johnson, former universities minister and now chairman of the education startup FutureLearn, urges Starmer to announce index linking of tuition fees, and do it soon. He calculates that in the first-year fees would rise to £9,500; in the second to £9,900. Alex Stanley, vice president of higher education at the National Union of Students says the government currently provides just 16 per cent of funding per student.

What’s more. Currently no-one except the body representing students thinks that anyone except students should get universities out of the mess that governments have got them into.