UK workers are on average £14,000 worse off per year in real terms now than if earnings had continued to rise at pre-2008 rates after the crash.

So what? The past 14 years have been the worst for British wage growth since the Napoleonic wars.

The Conservatives came to power in the aftermath of the global financial crisis with a pledge to rebuild an economy in which “everyone’s quality of life rises steadily and sustainably”. But if Laura Trott leaves a note to her successor at the Treasury it might read like this:

“Dear Chief Secretary,

I’m afraid there is no money… P.S. we’ve been having trouble with

- weak growth and poor productivity;

- chronically low levels of private and foreign investment;

- falling living standards; and

- a tax burden on track to reach its highest in 80 years.

Kind regards, and good luck! Laura”

Blame game. The financial crisis, Covid and energy price spikes were all factors largely outside government control. Brexit was not; nor were Liz Truss’s disastrous budget and David Cameron’s decision to engage in one the biggest deficit reduction programmes seen in an advanced economy since World War Two. Between 2010 and 2019, UK public spending fell from 41 to 35 per cent of GDP. During the same period the central bank interest rate didn’t go above 0.75. Some argue Britain would have been better off borrowing to invest.

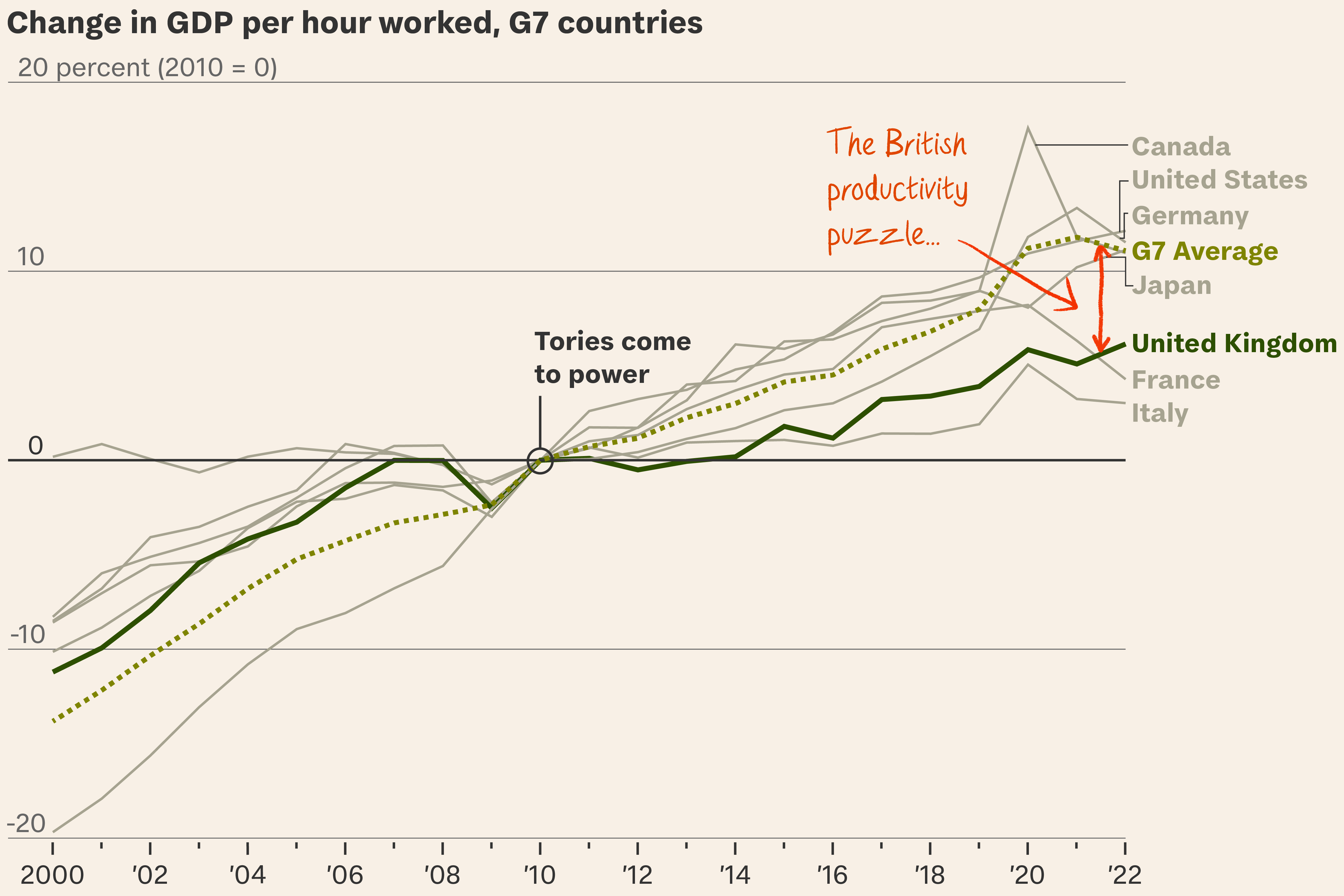

Puzzling productivity. “It isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything,” as the economist Paul Krugman has said. Output per hour worked has grown more slowly in the UK since 2008 than in every G7 country besides Italy. Overall output has been helped by one of the Tories’ few economic wins: an increase in the employment rate from around 70 to 74 per cent of the working age population.

“The only reason we’ve seen the economy grow overall since the last election is because we have more people, not because we are producing more per person,” says Carl Emmerson, deputy director of the IFS. That sets up a challenge for any government that claims it wants to curb immigration.

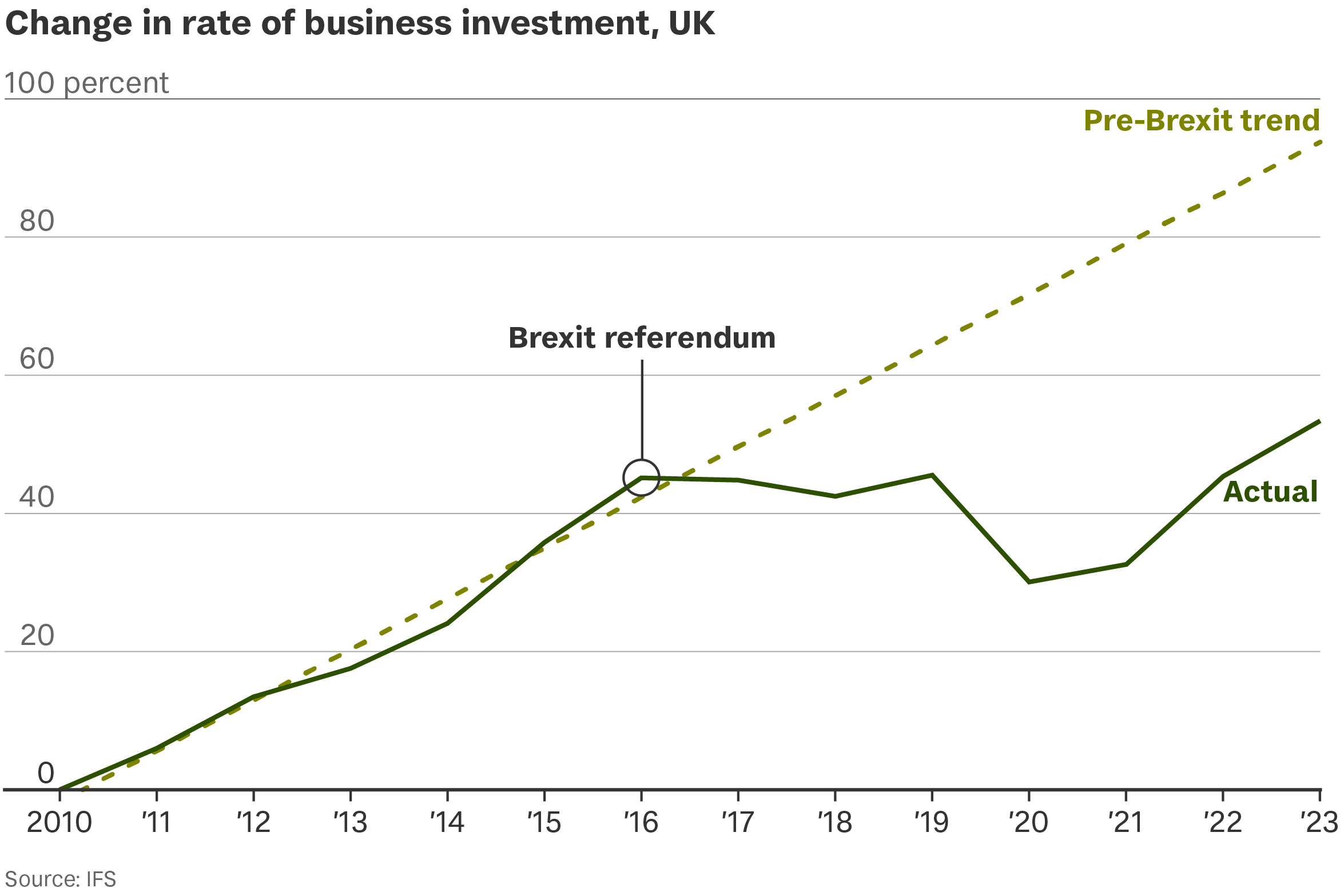

Brexit and trade. Investment needs stability, and Brexit was a wild ride. Total business investment fell sharply after June 2016 compared with the pre-referendum trend.

Trade in goods took a hit after Brexit – exports have contracted 13.2 per cent since 2019, far more than in any other G7 country. Foreign direct investment project numbers have fallen by nearly a third.

Trade in services trade, however, is booming, growing 14 per cent in the same period, which is faster than in France, the US and Japan.

Tax. During the 2010s tax revenue was stable. That has changed since 2019 with

- a hike in corporation tax effective from April 2023, and

- a six-year freeze on personal tax allowance thresholds, coupled with

- inflation, leading to extra tax revenues of around £40 billion a year.

Tax as a fraction of national income is now at its highest level ever – a case of pain delayed from the 2010s rather than avoided, Emmerson suggests.

Geography. The Levelling-Up white paper released by the Tories in February 2022 was regarded as a serious attempt to grow neglected regions of the UK. Some headway has been made in devolution and broadband coverage but progress otherwise is glacial or reversing: the gap in average employment rate between the top and bottom 10 per cent of local authorities is at its widest since 2005.

Inequality. By international standards, Britain has been an unequal country for the last 30 to 40 years. Its Gini coefficient is higher than all but six of the 38 OECD countries’. What marks out the last 14 years has been the combination of inequality and lack of growth.

Small mercies. Last year’s recession was short-lived and shallow. Pay is now rising faster than prices. Consumer confidence is climbing and might get a post-election bounce. But after 14 years, the UK economy is gasping for a break from poor choices and external shocks. The next chancellor has her work cut out.

Read the four-part series on the Tory record on the Tortoise website.

Chart of the week