The UK’s public spending watchdog has become an unofficial arbiter of fiscal policy

Days before the UK chancellor was due to deliver her spring statement, the Office for Budget Responsibility warned that her calculations for £5 billion in proposed savings from cuts to welfare would only deliver £3.4 billion.

So what? Rachel Reeves was left scrambling for other places for the axe to fall. Rather than being guided by her own grand vision, the chancellor has once again been pressured into action by officials. Last year, it was the winter fuel allowance; this time it’s deeper cuts to welfare. In both cases it is, at least in part, a case of the tail wagging the dog.

At a time when the public finances are historically tight because of Brexit, the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, the OBR’s forecast wields as much influence as the chancellor’s own plans.

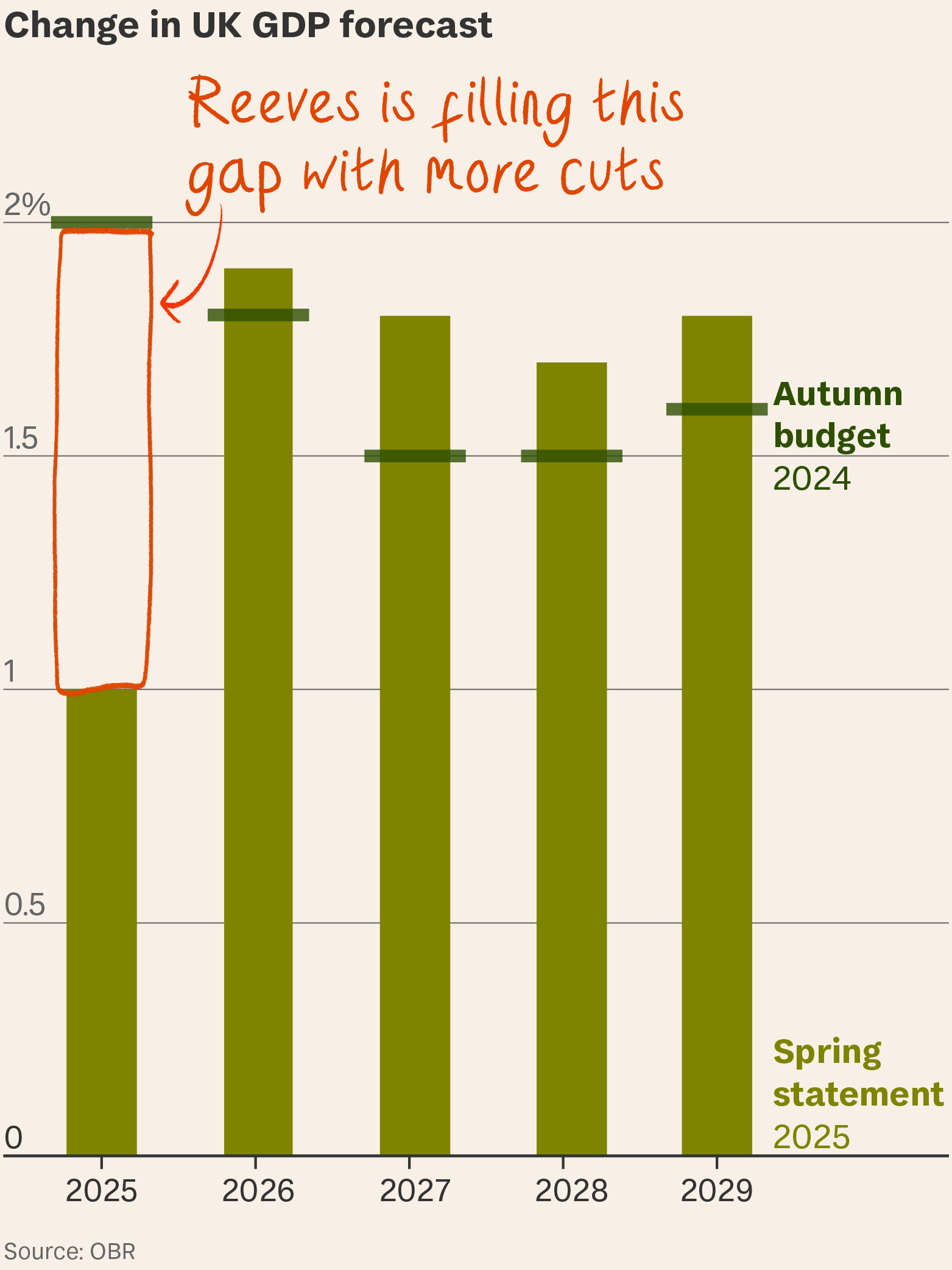

In particular the OBR has

- halved growth forecasts for 2025 to 1 per cent; and

- confirmed the £10 billion of headroom Reeves left herself last year had been wiped out, effectively breaking her fiscal rules by more than £4 billion; which in turn

- prompted Reeves to cut universal credit in order to restore the headroom and meet those self-imposed, iron-clad fiscal rules (but only just).

A word from our sponsor. Reeves opened with a word of thanks to the OBR chief Richard Hughes and team for their work. The chancellor has frequently painted herself as the polar opposite of Kwasi Kwarteng, one of her predecessors, in an effort to assure voters and the bond markets that Labour can be trusted with the economy.

But there is a risk that the OBR – no stranger to getting forecasts wrong – becomes a sacred cow. And on welfare at least, experts question the wisdom of letting this happen.

"Historically, cuts to disability benefits tend to make less savings than the OBR predicts in advance,” Alfie Stirling of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation says. “That’s because they often affect people that have really genuine health impairments. Therefore, these people are able to appeal or they’re able to find that they’re eligible for support elsewhere they weren't previously claiming.”

Words matter. Reeves mentioned the OBR 19 times in her statement compared with 13 mentions of “working people”. The 3.2 million families expected to lose out from welfare cuts didn’t get a look in.

The OBR did give Reeves the opportunity to talk up Labour’s planning reforms, estimated to boost GDP by 0.4 per cent within the next decade. “That is the biggest positive growth impact that the OBR have ever reflected in their forecast for a policy with no fiscal cost,” she said.

The OBR still wasn’t happy. It complained about receiving the benefits policy package late, which “hampered our ability to reflect these measures in our forecasts” – a technocratic but undeniable slap on the wrist.

Austere to nowhere. In the weeks before the statement, Reeves and her allies repeatedly insisted there would be no “return to austerity”. Labour backbenchers outraged by her cuts disagree.

But Reeves’s deference to the OBR is also giving flashbacks to 2010. An arm’s length body set up by George Osborne to poke Gordon Brown in the eye by casting retrospective shade on unreliable New Labour forecasts has become the arbiter of fiscal policy 15 years later. Reeves must be careful it doesn’t end up poking her back.

The alternatives for the chancellor to cutting spending are

- to raise taxes, which she has ruled out, or

- to break her own fiscal rules and borrow more.

Stirling says there’s “an asterisk” next to Liz Truss’s explosive decision to flout the rules (and defy the OBR) and that market responses to changing government debt tend to be driven by global factors anyway. Even so, for Reeves to break the “non-negotiable” rules would be an act of political harakiri.

What’s more… Her next fiscal event is the Autumn Budget. Before then, there’s a possibility the UK will be reckoning with Trump’s tariffs, which the OBR forecasts could slash growth by a further 1 per cent next year. All bets are off.