One of Britain’s leading public intellectuals reflects on how racism – and his experience of it – has changed over the last 50 years

Five or six minutes in, the ball was played out to Viv Anderson, the talented Forest and England right back. Immediately, every single person around me – my friend and his parents included – was on their feet making monkey noises. I sat there, idly wondering whether it was rude of me not to join in. By the time I’d mulled this over, everyone had sat back down amidst great good humour. Leeds lost. Plus ça change.

But things do change, even if the fate of football clubs doesn’t. The scene I witnessed at Elland Road would be unthinkable now (at least in the higher echelons of English football). And, in my own limited experience at least, such overt racism is largely a thing of the past. So much so that I hadn’t really thought about racism, or my experiences of it, for a very long time.

But then the riots happened over the summer. We saw violence, including an attempt to burn down a hotel housing asylum seekers, racist abuse, and even the UN urging the UK to curb racist hate speech. All of which conspired to make me revisit things I’d happily confined to the past.

The seriousness of the recent outbreak of racist violence should not be underplayed. Nor should the attempts by some politicians and associated cheerleaders to stoke anti-immigrant sentiment. If recent events have taught us anything, it is the fragility of the norms that have emerged over the last few decades and that, it seemed, made overt racism socially unacceptable.

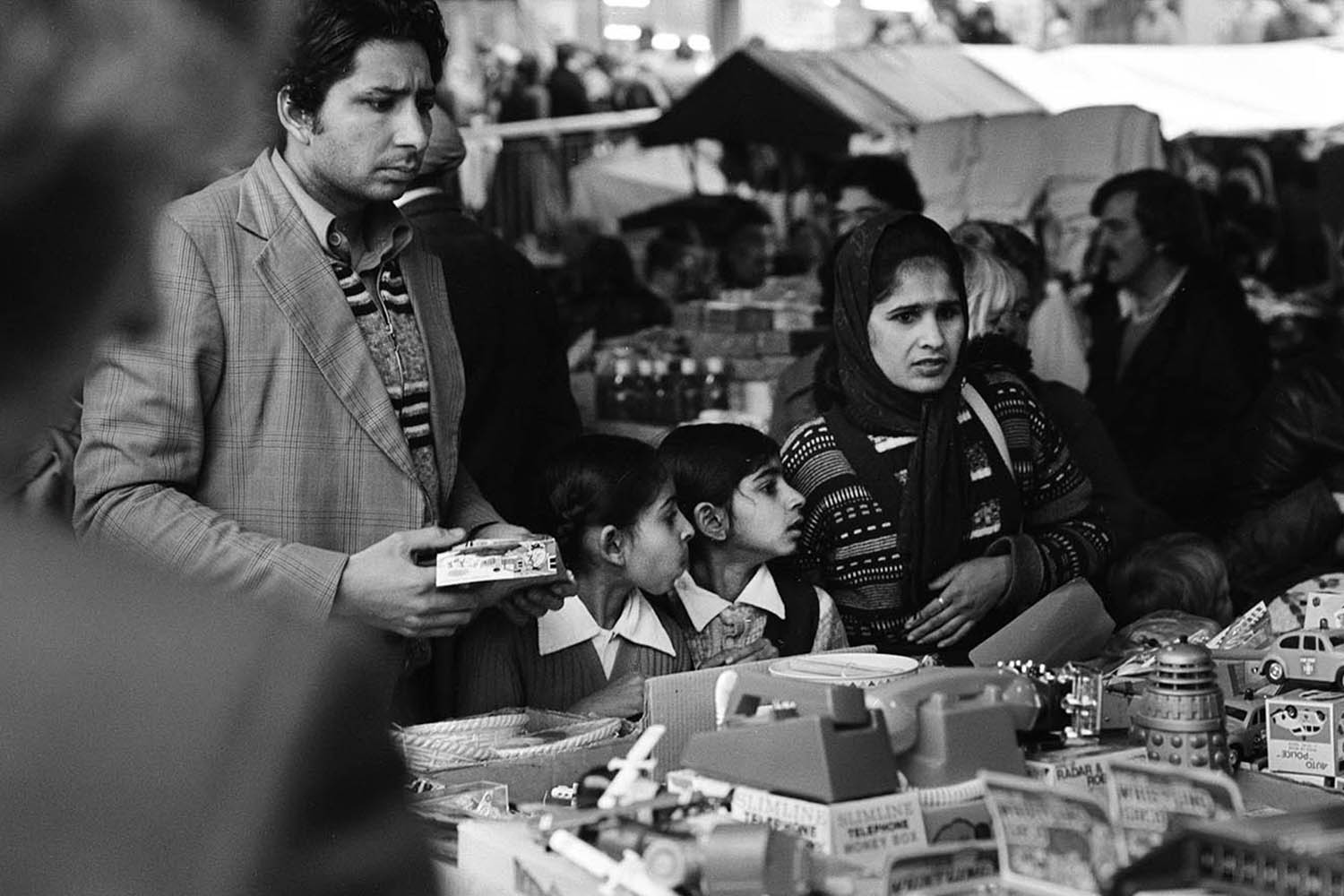

Yet the fact is things have changed beyond recognition since the years of my youth. The kinds of open, explicit racism that were a constant feature of my younger years have not troubled me for many decades. Fear is no longer a constant companion when I’m out and about.

Of course, my experience – past and present – is just that. Mine. I can’t and don’t claim to speak for anyone else, and my experience cannot be taken as generally representative. But it does seem to me that that experience is important and may be informative for thinking about racism and how those on the receiving end of it now view their country.

I grew up in Wakefield in West Yorkshire, not far from what was fondly referred to by some as the “Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire”. My family tended to refer (out of earshot of other people) to the “National Socialist Republic of Yorkshire”.

Racism was ubiquitous. Casual doesn’t really cover it. One teacher used to refer to me as “Mowgli”. By secondary school, my established nickname – amongst staff and students – was “choc”. Figure it out. The “p” word, “n” word and “w” word were an integral part of the vocabulary used in both “friendly” and threatening ways. “I hate Pakis, but you’re alright, you’re English” was something said to me more times than I can remember. It was intended as a compliment.

Racism was part of the fabric of life. The serialisation of Roots caused general hilarity and an opportunity to have some fun. Whiplash noises greeted me round the school. A bunch of sixth formers sat around in the changing rooms as I was rushing to leave, discussing whether it would be possible to hang someone with a school tie. One evening, getting on the bus home, I paid the driver but forgot to grab my ticket. Halfway up the stairs, with the bus still stationary, the booming voice rang out: “Oi, Kunta Kinte. Your ticket.” I froze. Every single eye was on me as I went back to get it.

We should keep this in perspective. Wakefield was not the American deep south. The threat of physical violence that ultimately lay behind the name-calling was (relatively) mild rather than fatal. And these were not threats of sexual violence that are so disproportionately aimed at women.

As importantly, I grew up in relative privilege. My parents were doctors. More important still, they were loving and generous and extremely liberal: they wanted me to fit into UK society (and actively discouraged me from learning my maternal language for fear it would impact negatively on my English).

I wasn’t raised – as some were – in the kind of neighbourhood where racist graffiti proliferated and white thugs routinely smashed windows. Little wonder those communities tended to batten down the hatches and eschew social contact with others. Racism fostered precisely the kind of segregation and lack of integration that racists claim to hate.

Yet there was physical violence. I was beaten up three times in the city centre, once badly enough to merit a quick trip to A&E (my swollen lip earned me a far better grade in my German A Level Oral than I deserved). My (white) girlfriend was once threatened by a bunch of blokes as we walked through town together. We very occasionally had dog excrement put through our letter box and my dad once had to stamp out a burning piece of paper that some idiot posted through our front door.

And there was a constant threat. When I reached the age of evenings out in pubs, I would never wander round town alone on a Friday or Saturday night. I’d cross the road to avoid groups of young men.

Even as a small child, I found excuses to avoid going to the shops with my mum on a Saturday morning, anxious to avoid that burning sense of humiliation that came with people shouting “go home Pakis”.

I was a Leeds United fan, but I went to very few games thanks to the ever-present threat of violence and abuse – from home fans. In the 1970s, it seemed easier to get hold of a copy of National Front News than the matchday programme at Elland Road.

And then there was the perpetual, draining watchfulness. Avoiding eye contact in pubs, avoiding groups of young men, being alert for abuse. John Howard Griffin put it better than I ever could in his harrowing, wonderful book Black Like Me: “In a jumble of unintelligible talk, the word ‘nigger’ leaps out with electric clarity. You always hear it and it always stings.” You do indeed. Even whispered from several rows back on the bus. It was hard ever to really relax when out and about.

Being brought up in a house where the English were “they” shapes how you view your country. So, too does a sense that there are people who simply don’t want you there. I remember in 1979 my parents discussing whether to move back “home” to India as the National Front prospered and racism seemed more commonplace. Home, of course, was a problematic concept for me. Whatever my problems in Yorkshire, I spoke the language and had friends there. India was a place we visited where people stared at me for being so obviously westernised. As a child, I did not feel particularly comfortable whichever country I was in. Less a “Somewhere” or “Anywhere” than a “Nowhere”.

My reaction was to try desperately to fit in. I strove to be more English than the English. Hence the strong Yorkshire accent my parents hated, and which people could barely understand when I arrived at university. Hence, too, my stubborn attachment to a football team whose fans were known for their racism. And, of course, my determination in my younger days to support England at all sports – particularly against India.

It amazes to this day me how profoundly and abruptly all this changed when I left home to go to university. I still live in Oxford and have only encountered racist abuse once – literally once – in the forty years I’ve lived here.

I’m not for a moment suggesting that discrimination no longer existed in English society. But, for me, after I’d left home, it manifested itself in more subtle, more “civilised” ways than it continued to do in Wakefield. When my dad retired in the late 1980s, he walked up to try and join the local golf club and was told to his face that “we don’t want people like you here”. The first time I was invited to give a talk at Chatham House – sometime in the mid-90s – the receptionist was scrupulously polite, but it soon transpired he thought I was a taxi driver.

In fact, it took a period abroad for me to appreciate the degree to which I’d come to take this sort of thing for granted. In 1999, I spent some time living in New York City. People there were no less prejudiced. But there, it worked in my favour. A New Yorker who saw a South Asian assumed they were dealing with a successful entrepreneur or a brain surgeon. Total strangers treated me fantastically. God, I loved it. Though, as a salutary footnote, following 9/11 it was a fair bet that any yellow cab festooned with the Stars and Stripes was driven by a South Asian. It was their equivalent of my broad Yorkshire accent.

Even in this country, attitudes and assumptions have shifted remarkably since the 70s and 80s. “I’m not racist, but” is hardly the most encouraging start to a sentence. Those who deploy it on social media do tend to contradict the assertion quite quickly. The phrase does, however, speak to the fact that open racism is now socially unacceptable.

At the same time, and equally importantly to my experience, I think, the image of India and of Indians began to change. Indian culture – and of course Indian food – have become fashionable. India itself has grown in power, wealth and assertiveness (look at the Indian Premier League). Indians began appearing in sitcoms that weren’t about the Raj. England and Scotland have both had Asian leaders.

Slowly, and initially almost imperceptibly, being Indian became kind of cool.

Going to watch Leeds United is no longer a determined act of tribal loyalty or, as my mother used to put it, stupidity. I haven’t faced racial abuse at Elland Road since the 1980s, and the monkey chants have also gradually disappeared. England games in the 1990s were another matter, reinforcing in me an identity that was more regional than it was national.

Perhaps the last flicker of my old fears came in the late 1990s. When my son was born in 1998, my only reservation about my favourite name – Samuel – was that he’d get called “Sambo” at school. I remember the giggles and furtive glances in my direction as we read Little Black Sambo at primary school. Yet, when I asked him recently (he’s in his twenties now) whether this had happened, he looked at me with blank incomprehension (his default expression when dealing with me, but still).

The most obvious conclusion to draw from all of this is that the racism prevalent in this country in the 1970s and 1980s has no equivalent today. This country has been transformed, and for the better, in terms of social attitudes towards race.

This has had a curious impact on me. Greater confidence in my Englishness has made me able, belatedly, to openly support an England football team I had hitherto associated with right-wing thugs sporting the cross of St George and revelling in their racist chants.

Paradoxically, that same confidence allows me wholeheartedly to support India at cricket – even – indeed especially – when they’re playing England. This is why the so-called Tebbit test was so ridiculous. For me at least, it was security in my Englishness that allowed me openly to support India.

Though I’m perhaps also guilty of a degree of naivety. I’m so pleased not to feel scared that I’m less worried than I should be by persistent, but less visible forms of discrimination. I’m not for a moment saying racism no longer exists. But I am profoundly grateful it is no longer in my face as it once was. This has perhaps obscured the continuing problems that minorities face in today’s England. Perhaps it makes me complacent. We know that there are still people in some parts of the UK who suffer direct forms of racism, and the act of writing this article has made me realise, I should probably take more interest in that.

The improvements we have seen are to be welcomed, but they should not be taken for granted. When the recent riots happened, I was surprised by my own reactions.

For the first time in decades, I recently crossed a road to get out of the way of a group of drunk white men.

While we’re clearly not back in the dog days of the 1970s, I’d underestimated just how fragile the new consensus was.

Writing this, I’ve come to realise how appallingly selfish I’ve become. How my relative security made me blind to the insecurity of others. In my anxiety not to appear hypervigilant, I’d not called out as clearly as I should have the careless and provocative rhetoric, the talk of immigrants as vermin, the scaremongering about an “invasion”, the lazy elisions of “British” and “British-born”.

One of the big changes between then and now is the presence of social media and the ease with which fake news can spread (like claims the Southport murderer was an Islamicist who had arrived in a small boat). This has resulted in the paradox pointed out by Sunder Katwala that, in a society with ever-fewer racists, there might be wider experience of racist abuse and threat than was the case 20 years ago.

I’m still sensitive. So, too, I imagine, are all those who were on the receiving end of the casual, cruel, continuous racism of the 1970s. I hope my recollections about my childhood help explain why.

Looking back, it seems to me that my social class and the relative affluence of my parents have been far more determining factors in terms of what I have achieved and what I have become than my race. Financial status and education have a much greater impact on your life chances than being born non-white. I passed the 11 plus and went to a grammar school where racism was a fact of life, but physical violence was not. My sister was stabbed at the local secondary modern.

Racism was an unpleasant, constant feature of my early life, but it didn’t get in the way of my progress. This is simply not the case for others. Racism is insidious. We have made progress, and we should remind ourselves of that – even though that progress remains fragile and insufficient.

Anand Menon is Professor of European Politics and Foreign Affairs at King’s College London. He is also director of UK in a Changing Europe, whose latest publication, Minorities Report, on the attitudes of Britain’s ethnic minorities, is published on 8 October.