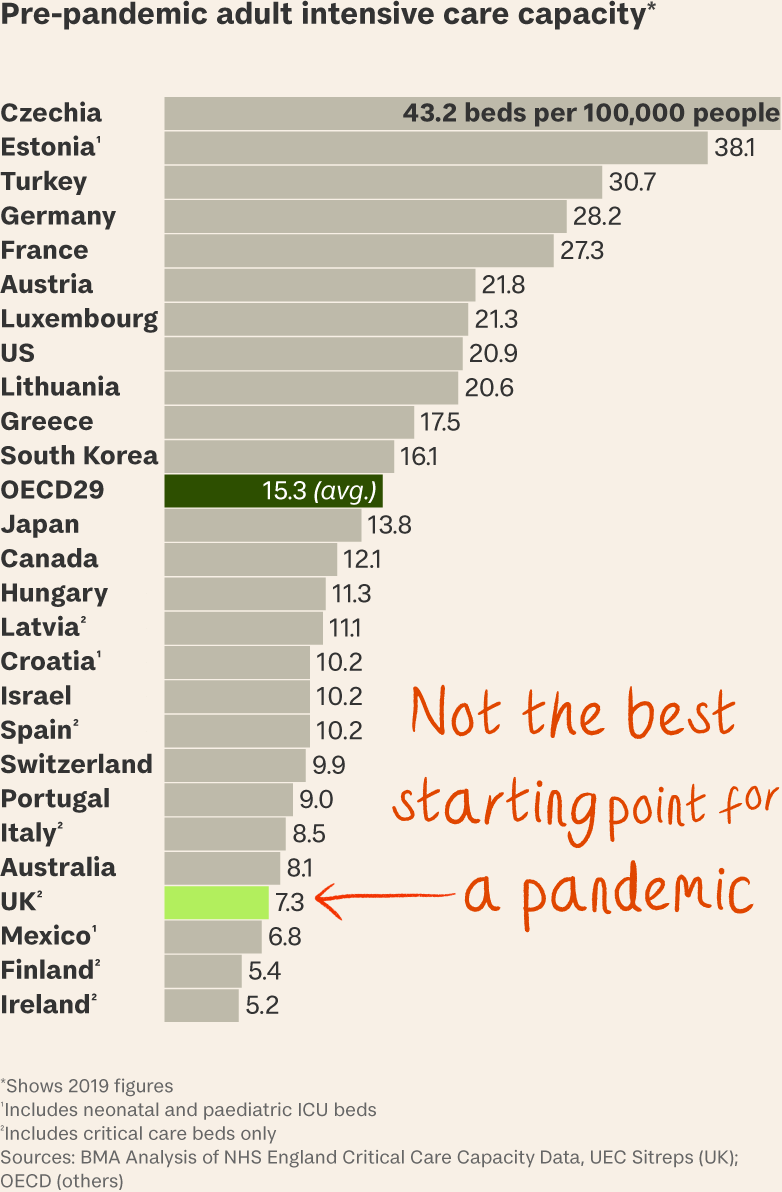

Transferring a critically ill patient from one intensive care unit to another can free up beds where they’re needed. But it involves so many resources and so much risk that in a typical winter even a big UK teaching hospital might not try it even once. So what? During Covid, one hospital transferred out 28 ICU patients in ten days. Another moved 70 critically ill patients in the first wave of the pandemic and 110 in the second. A third transferred out 17 patients in one night. The numbers are striking, but they barely begin to tell the story of Covid’s human cost for the NHS – a story unfolding in exquisite detail at the official Covid Inquiry in London, and until last week falling largely on deaf ears. Then, on Thursday, Kevin Fong took the stand. As noted here, in 90 minutes of searing testimony he related his findings as a consultant anaesthetist tasked with liaising between frontline ICUs at the peak of the pandemic and NHS headquarters in London. They were sobering.

Fong told the inquiry that

- NHS management knew least about the most hard-pressed hospitals because the hospitals had no time to collect information and report back on what they needed;

- data alone didn’t capture the reality anyway – of small hospitals whose most stable ICU patients were transferred out, leaving most of the rest to die; of nurses so frightened of going to work that they would vomit on the way in; of the ICU that had to admit six of its own staff, four of whom died; and

- by January 2021 NHS staff were presenting with symptoms of PTSD at a rate similar to combat veterans after service in Afghanistan.

His 35-page written statement to the inquiry offers anecdotal evidence of a health service close to collapse even though preventing collapse was the main aim of government policy.

On planning. In December 2020, as wave 2 built, the ICU matron of a large district general hospital said it had overstated its potential capacity with “surge numbers [that] were cloud cuckoo, based on nothing, and super-surge numbers that were completely unrealistic”. The ICU clinical lead at another hospital called the idea of a super surge (temporarily improvising an increase in ICU capacity) “a work of fiction” created by a regional management team without consulting frontline units.

On personnel. Staff said they felt a sense of mission shared with the public in wave 1 but felt exhausted, frightened and alone in wave 2. One ICU matron said “people were absolutely terrified” and spoke of watching a colleague crying in her car as she prepared for a shift. Others spoke of

- feeling “isolated, vulnerable and afraid without the support they needed” when forced to treat critically ill patients in ad-hoc overflow areas;

- being “haunted by the cries of… loved ones” after having to hold up phones or iPads for family members barred from being with dying patients in their final moments; and

- ‘watching bodies being wheeled out one day in a line of trolleys, “like trains”.’

The statement says illness and exhaustion (as well as maternity leave) led to dangerously high staff attrition rates – from 1:1 to 1:4 or 6 in ICU nurse-to-patient ratios and from seven to two “whole time equivalent” ICU consultants at one hospital over the course of the pandemic. More than 34,000 nurses quit the NHS in the year to October 2022. “If we do not care for our carers they will not be able to care for our patients,” Fong writes.

On the definition of collapse. One district general hospital he visited in December 2020 had no spare staff, wards and overflow areas all full, not enough oxygen, a lead clinician wheezing from long Covid and ICU nurses in adult diapers because they had no time for toilet breaks. “It is the closest I have ever seen a hospital to being in a state of operational collapse,” writes Fong, who was on duty at University College Hospital in London on the day of the 7/7 bombings in 2005.

“This is [expletive] important,” he said at the weekend. “Lots of people died. Our only opportunity to learn is here and now.”

What’s more… “The attention span of the public really can’t be the determining factor in how seriously we take this.”