Columbia’s tent camp may not last, but it gave a glimpse of the future.

Columbia University’s president said on Monday that talks with pro-Palestinian protesters had failed and urged students camping on college grounds to “voluntarily disperse” or face suspension.

So what? If it was that simple, they would have left already – and Minouche Shafik’s job would be safe. But they haven’t, and it isn’t.

Columbia’s students set up tents two weeks ago in a show of support for Palestinians, as the death toll from Israel’s months-long offensive in Gaza reaches 34,000 people. But the sit-in protests – now a feature of college campuses nationwide – also touch on:

Academic freedom. Supporters say the student protesters represent a long tradition of college activism – from Berkeley and Columbia in the 1960s to Kent State in 1970. One member of Columbia’s faculty said Shafik’s decision to call in New York police on 18 April “degraded the mission of a great university, which is a place for learning and debate”.

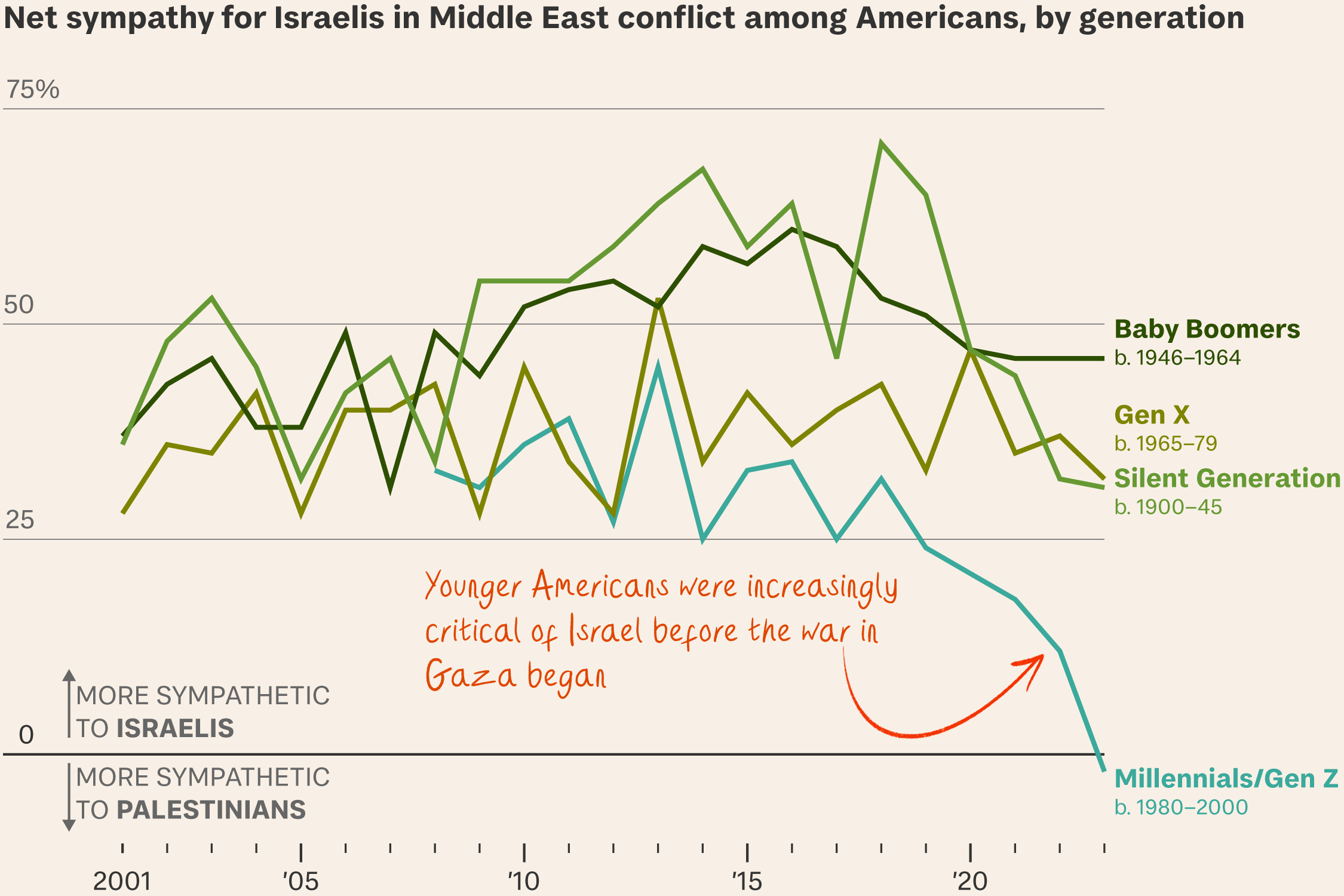

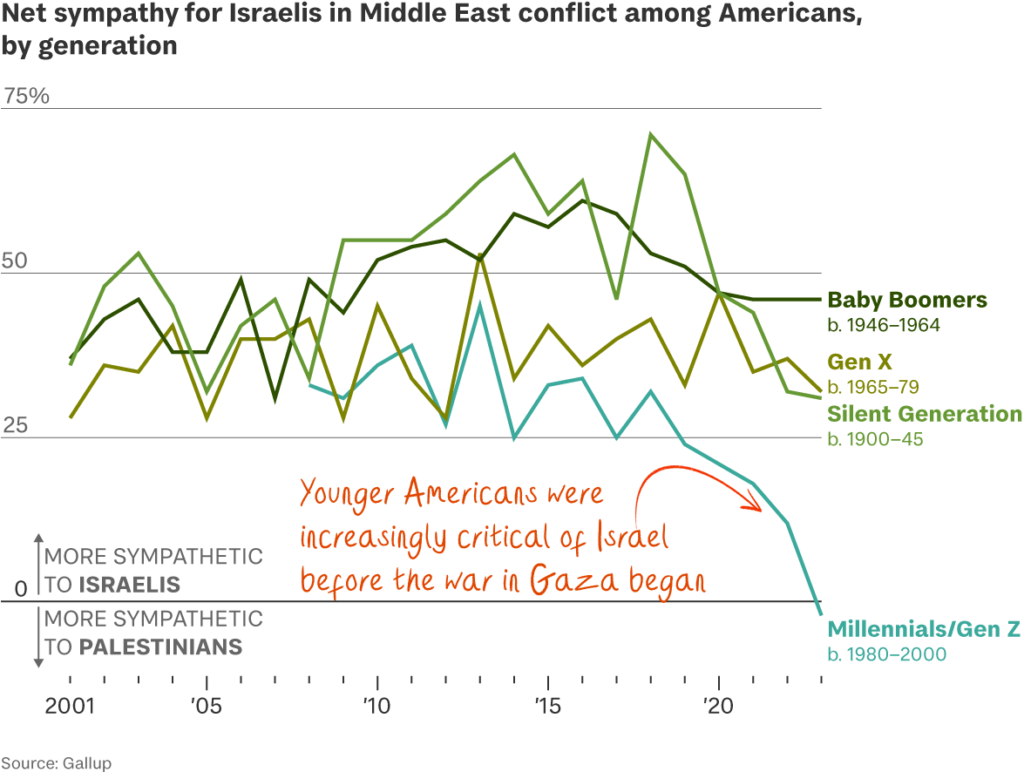

Generational shifts. The campus protests have revealed shifts in US opinion on Israel that have been developing for years. A 2023 Gallup poll found net sympathy towards Israel at +46 points among those born between 1946 and 1964; that drops to -2 among those born after 1980. In a 2021 survey of Jewish voters, respondents under 40 were twice as likely to agree that Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinians as those over 64.

Anti-semitism. The line between legitimate criticism of Israel and antisemitism is “exactly what there is argument about right now and it is not impossible it has been crossed,” writes Mark Mazower, a Columbia history professor. Some Jewish students have joined the protest camps; others feel unsafe on campus.

An election. Democrats are more divided on Gaza than Republicans, which hands the GOP an opportunity. Mike Johnson, the US House Speaker, visited Columbia last week and called on Shafik to resign if she can’t bring the protests under control; some called on Biden to mobilise the National Guard to “break up these mobs” (the NYPD described students as “peaceful.”)

The bigger question is whether Democrats can still portray themselves as the “steady hand at the helm”, says Dan Sena, a Democratic strategist. “Things that create national chaos like this make that harder to do.”

By the numbers

- 108 – Columbia protesters arrested on 18 April

- 900 – people arrested since then at campus protests across America, approximately

- 9 – length of Shafik’s tenure as Columbia’s president, in months

- 28 per cent – Biden’s overall approval rating among 18-29 year-olds

How it started. The “Gaza Solidarity Encampment” was set up on 17 April, as Shafik testified to a committee of the US House investigating campus antisemitism. She denounced antisemitic behaviour by students – in much stronger terms than the heads of Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania last year, who later resigned – and said there would be consequences. The NYPD was called in the following day.

The ensuing explosion of protest camps shows “you can’t arrest your way out of this,” says Simone Zimmerman, a Jewish American activist. “Arresting students, censoring critical voices, shutting down protests, none of this makes young Jews or anyone safer.” Other approaches include Harvard closing off areas to the public and Cornell suspending students, without arrests.

Where it’s going. Students want universities to divest from Israel and weapons manufacturers. Columbia protests want the school to sell holdings in Google, which provides cloud services for the Israeli government (Google has sacked 50 workers over protests against the contract). They point to the 1980s, when Columbia sold $39 million of stock it held in US companies doing business in apartheid South Africa.

Shafik said on Monday that Columbia would not divest, but offered to make the school’s holdings more transparent and invest in health and education in Gaza.

What’s more. Behind Columbia’s tents, stadium seating is going up for the university’s graduation on 15 May – for a student cohort whose high school graduations turned into pandemic drive-through ceremonies. The University of Southern California cancelled its main graduation ceremony last week.

What’s much more. Hopes are rising of a Gaza truce and hostage release deal.