The Democrats and Republicans have chosen their presidential candidates but Biden and Trump will not be the only names on the ballot. That could mean trouble for both.

Robert F Kennedy Jr’s presidential campaign announced last week that it had collected the 10,095 signatures required for appearing on the presidential ballot in Nevada.

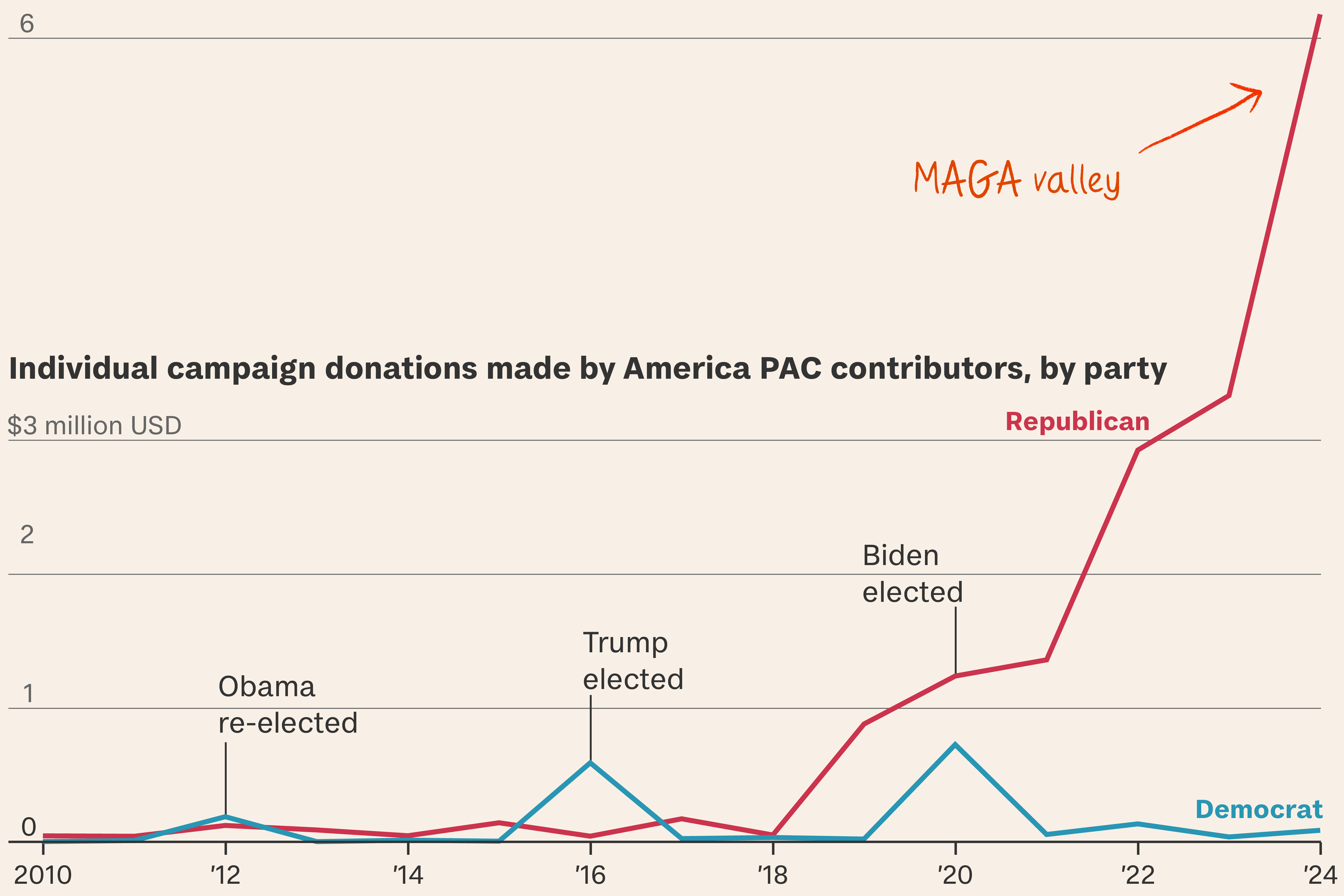

So what? Kennedy is polling at around 15 per cent in a three-way race with Biden and Trump, and Nevada is the first swing state in which he’s passed the signature threshold. The reality that President Biden will be facing multiple, high-profile independent and third-party candidates as well as Trump is starting to rattle the Democratic political class.

- Democrats are right to be worried.

- Republicans should be, too.

- But not for the obvious reasons.

Who? The independent and third-party candidates most likely to appear on ballot papers in November are:

- RFK Jr – the 70-year-old nephew of John F Kennedy Jr who’s running as an independent and is known for his opposition to vaccines and for right-wing conspiracy theories.

- Cornell West – an influential 70-year-old author, public intellectual and self-identifying socialist.

- Jill Stein – this will be the third election in which the 73-year-old has served as the Green Party’s presidential nominee.

- No Labels – a centrist, “third-way” party that says it will run a “unity” ticket (one Democrat and one Republican) in all 50 states. The problem seems to be getting anyone to join that ticket.

- Libertarian Party – will choose its nominees in May.

State of play. Today, eight months out from Election Day, the Real Clear Politics polling averages show…

- Trump leading Biden by less than two points in a two-way race;

- Trump leading Biden by four points and Kennedy with 15 per cent in a three-way race; and

- Trump leading Biden by almost three points, followed by Kennedy at 12 per cent, West at 2.5 per cent and Stein at just under 2 per cent in a five-way race.

These numbers are the reason for Democrats’ growing panic: Biden’s losing.

But it’s complicated. Accurately polling third-party support is notoriously difficult, and pollsters have overestimated third-party and independent support in almost every election since 2000.

Candidates who don’t run under either major party banner also tend to lose support as an election nears. In other words: even if the polling was on the nose, for someone like RFK Jr, 15 per cent in March almost never means 15 per cent in November.

Even so, third party candidates who stay the course tend to go down in history.

Ross Perot, 1992. Perot – a wealthy businessman from Texas running as a centrist independent – captured 18.9 per cent of the vote. While arguably the most successful independent of the modern presidential era, Perot failed to win a single state. Today’s best estimates also suggest he had a negligible effect on the overall outcome of the election, pulling votes equally from President George H W Bush and then-Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton.

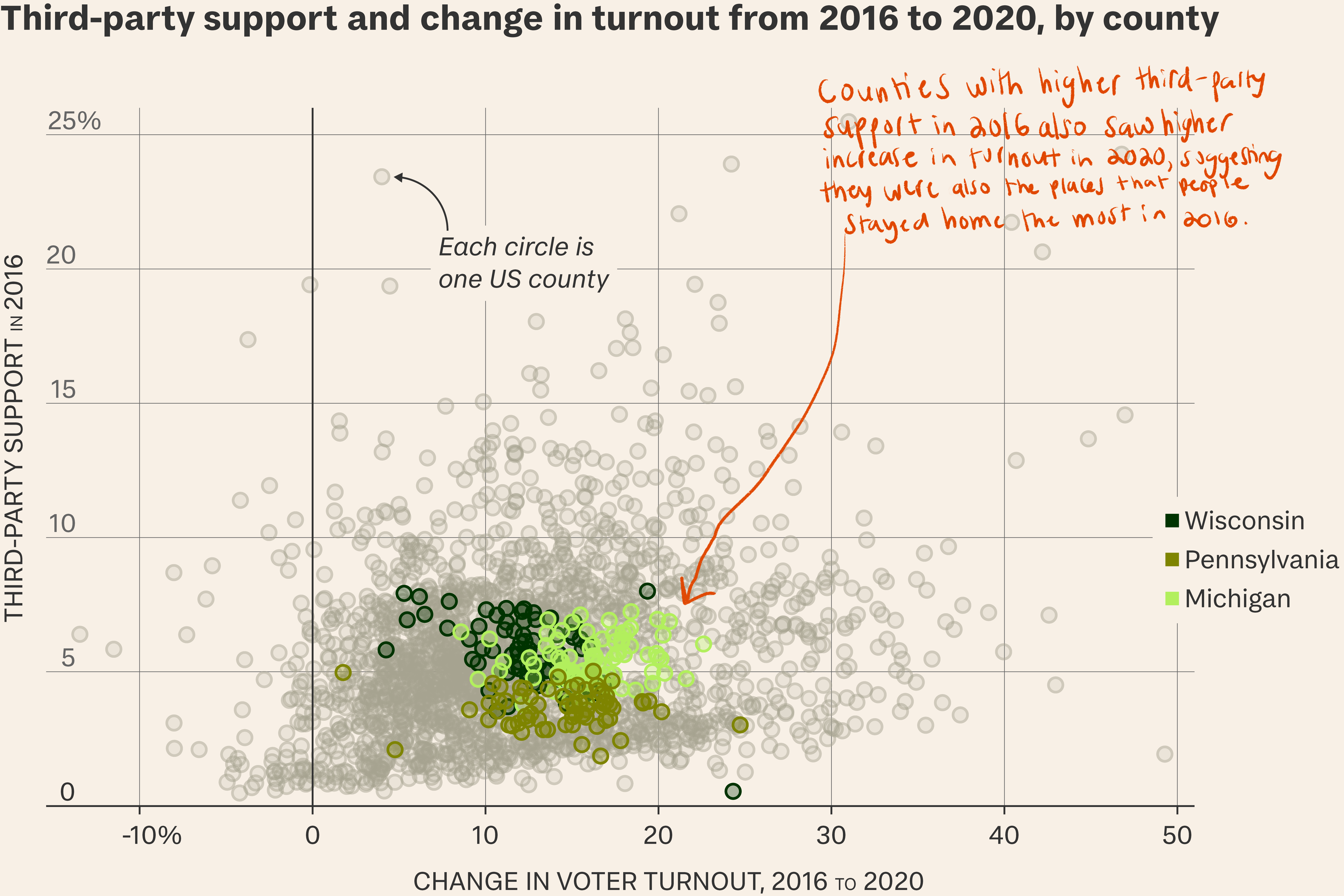

The lesson here is that you have to look past national support: just because RFK Jr or Cornell West are polling high nationally doesn’t mean they post a threat to Biden in places that matter.

Ralph Nader, 2000. In 2000, George W Bush won Florida (and thus that year’s presidential election) by 537 votes. Despite winning less than 3 per cent of the vote nationally, Nader – the left-wing Green Party’s nominee – won almost 100,000 votes in Florida.

The lesson here is that all it takes is one state – or even one county – to turn an election.

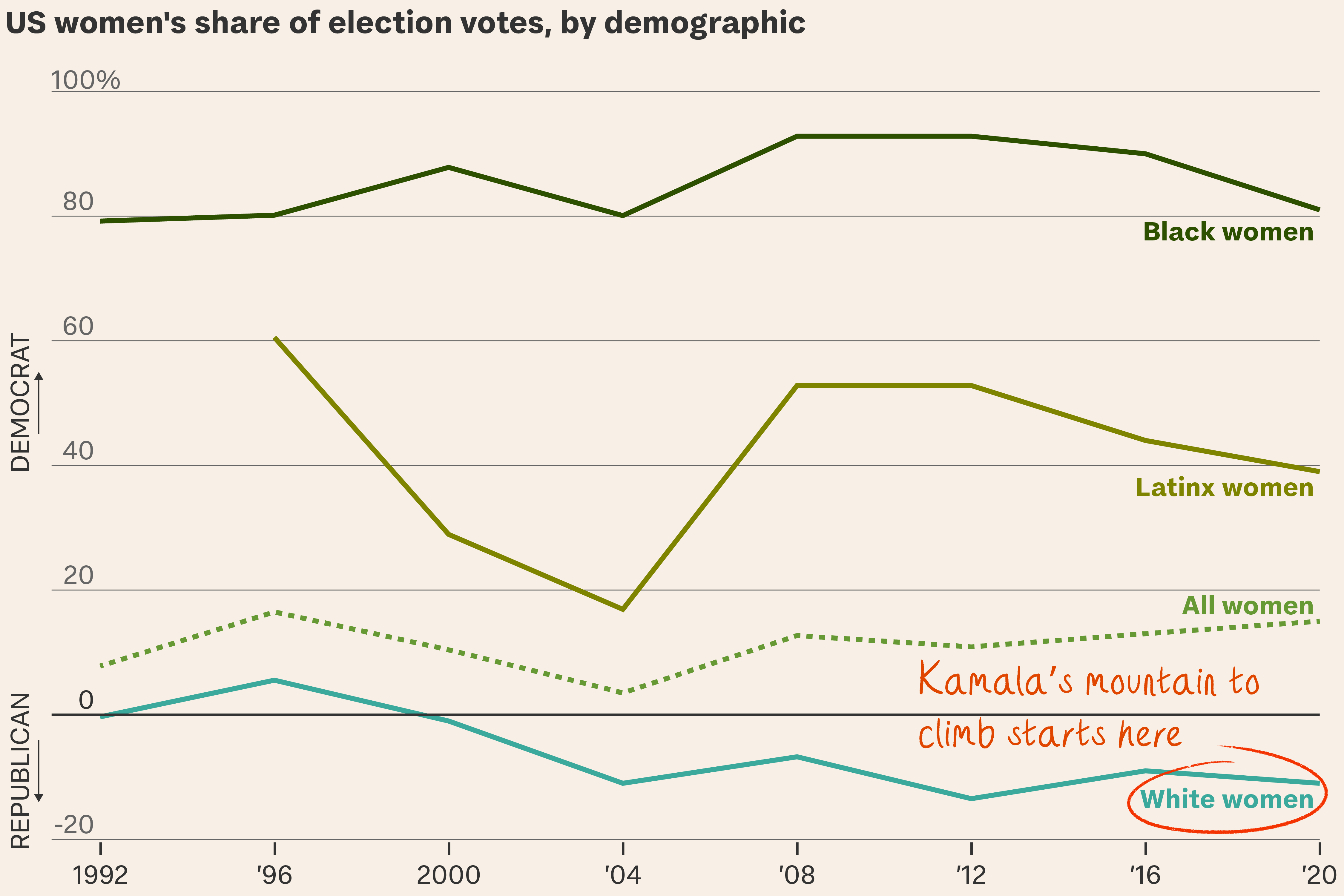

Jill Stein, 2016. If Hillary Clinton had won Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania in 2016, she would have become the country’s first woman president. In all three states, Green Party nominee Jill Stein captured more votes than Trump’s margin over Clinton.

But that’s not how elections work. The lesson the Biden campaign should take from Clinton in 2016 is that her loss had very little to do with third parties. Third-party and independent support in polls is often partially a proxy for people who won’t end up voting, because there’s no good bureaucratic way to identify them, and nor do people like telling pollsters they’re not going to vote. In 2016, the number of people who decided to stay home probably hurt Clinton more than the number who voted for Jill Stein. And the signs – both in the polling numbers and primary results – are that this could be a problem for Democrats again.

For both main parties, turnout counts.

What’s more… Biden also has a young people problem: in Michigan especially, his refusal to back an unconditional ceasefire in Gaza has hurt his ratings with first-time voters. To win, he needs them.

More than 70 countries are holding elections this year, but much of the voting will be neither free nor fair. To track Tortoise’s election coverage, go to the Democracy 2024 page on the Tortoise website.