Liz Thomson looks at the cultural legacy of <em>The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan</em> – and how it intersects with the artist’s own contradictory image

Sixty years ago this May Bob Dylan released his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. That summer 250,000 people marched on Washington to demonstrate that in 1963 black lives mattered. Dylan himself sang from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial as Dr Martin Luther King spoke of his dream.

Dylan always insisted that he never wanted to be a spokesman for his generation but his silence during America’s recent agonies seems shameful. And he has been almost as silent on an issue last year that will stain his reputation – the use of an autopen on a high-price, limited “signed” edition of his book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, and on unspecified “signed” artwork.

Dylan claimed to have been ill-advised, to have made “an error of judgement” in the face of a looming deadline while suffering from vertigo. Both his publisher and his art gallery have declared that they were unaware of Dylan’s use of an automated signing device. Yet the question remains: who knew what and when? Money has had to be refunded to fans who bought items assuming Dylan had signed them himself. It’s the sort of scam the angry young Dylan might have turned into a song, one of his sardonic talking blues.

In recent years, Dylan has helped advertise banks, cars and even lingerie. That seemed merely crass and commercial. Now he appears greedy and duplicitous.

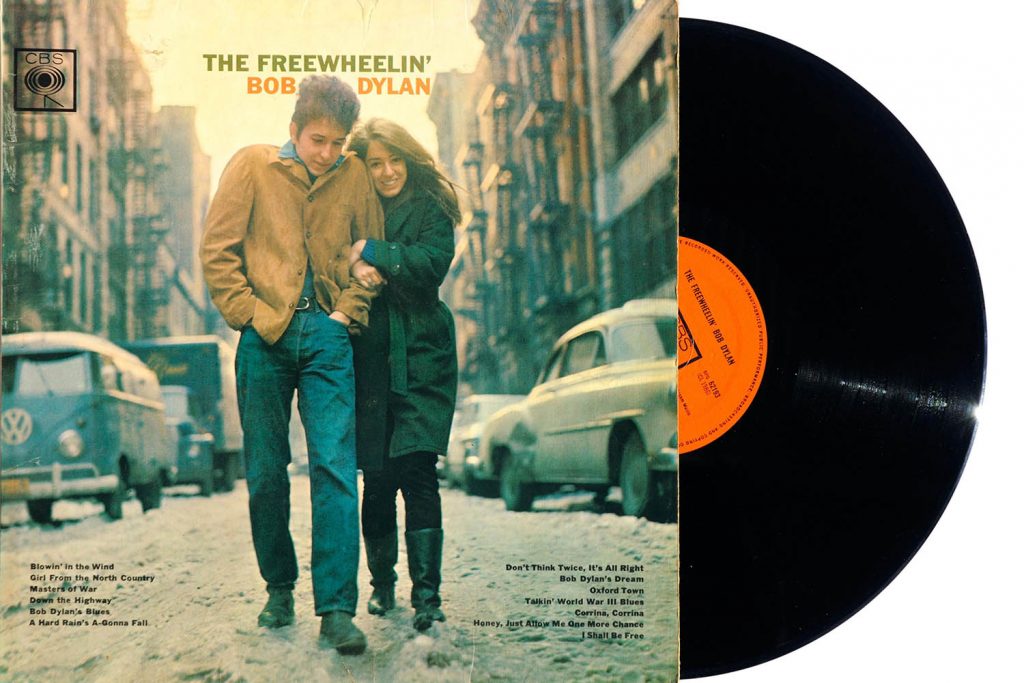

The cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, that first appeared in May 1963, is worthy of that often misused word “iconic”. It has come to “signify” so much more than was imagined (much less intended) when the Columbia Records photographer Don Hunstein arrived at a tiny walk-up apartment at 161 West 4th Street (above Bruno’s Spaghetti Shop) in Greenwich Village where Dylan and Suze Rotolo were paying $60 a month to live.

After taking a few frames of Dylan seated in a ratty old armchair that had been rescued from the sidewalk, it seemed a good idea to venture into the slush and frigid cold of Jones Street. The inadequately dressed young lovers huddled together for warmth as Hunstein clicked away.

Rotolo recalled that Dylan “chose his rumpled clothes carefully”, but the image was created on the fly, without recourse to make-up artists and stylists, and it broke the mould. “It is one of those cultural markers that influenced the look of album covers precisely because of its casual down-home spontaneity and sensibility,” wrote Rotolo in her affecting memoir A Freewheelin’ Time (2008).

That image has been widely imitated – Fred Neil at the crossroads of Bleecker and MacDougal; Simon and Garfunkel on the 5th Avenue–53rd Street subway, the Ramones on the Bowery, the Beatles on Abbey Road – but few musicians allowed their girlfriends to share centre-stage. Rotolo, who died in 2011, was the subject (or object) of two of the record’s songs and as someone steeped in social and political action there’s no doubt that she had helped shape his world view. Perhaps Hunstein intuited all that when he suggested she be in the picture.