What just happened

- Nurses in the UK announced plans for their first ever strikes next month.

- Iran arrested a top footballer in a presumed warning to its World Cup team.

- Europe’s space agency selected a British Paralympian to join its next generation of astronauts.

Eurovision has changed its voting rules. For the first time, the whole world will get a vote.

So what? As Russia tries to crush Ukraine and Qatar denies the existence of gay rights, Eurovision’s makeover is a surprisingly big deal.

Eurovision is an annual music competition run by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), an alliance of national broadcasters pitting 37 countries – mostly – in Europe against each other in a week-long spectacle culminating in a three-and-a-half-hour long grand final.

To win: artists need to appeal to voters at home and juries of industry experts representing the participating countries. The catch: you can’t vote for your own country.

How? By performing an original and catchy song not previously released elsewhere, ideally with extravagant choreography and pyrotechnics.

The prize: glory in the grand final and the chance for your country to host the competition the following year.

This year, that glory went to Ukraine’s folk-rock Kalush Orchestra for its song “Stefania”. However, because of the war, the UK (which came in second with Sam Ryder’s “Space Man”) has stepped up to host next year’s competition in Liverpool.

The change. This week the EBU announced some of the most significant rule changes to the Eurovision voting system in its 67-year history:

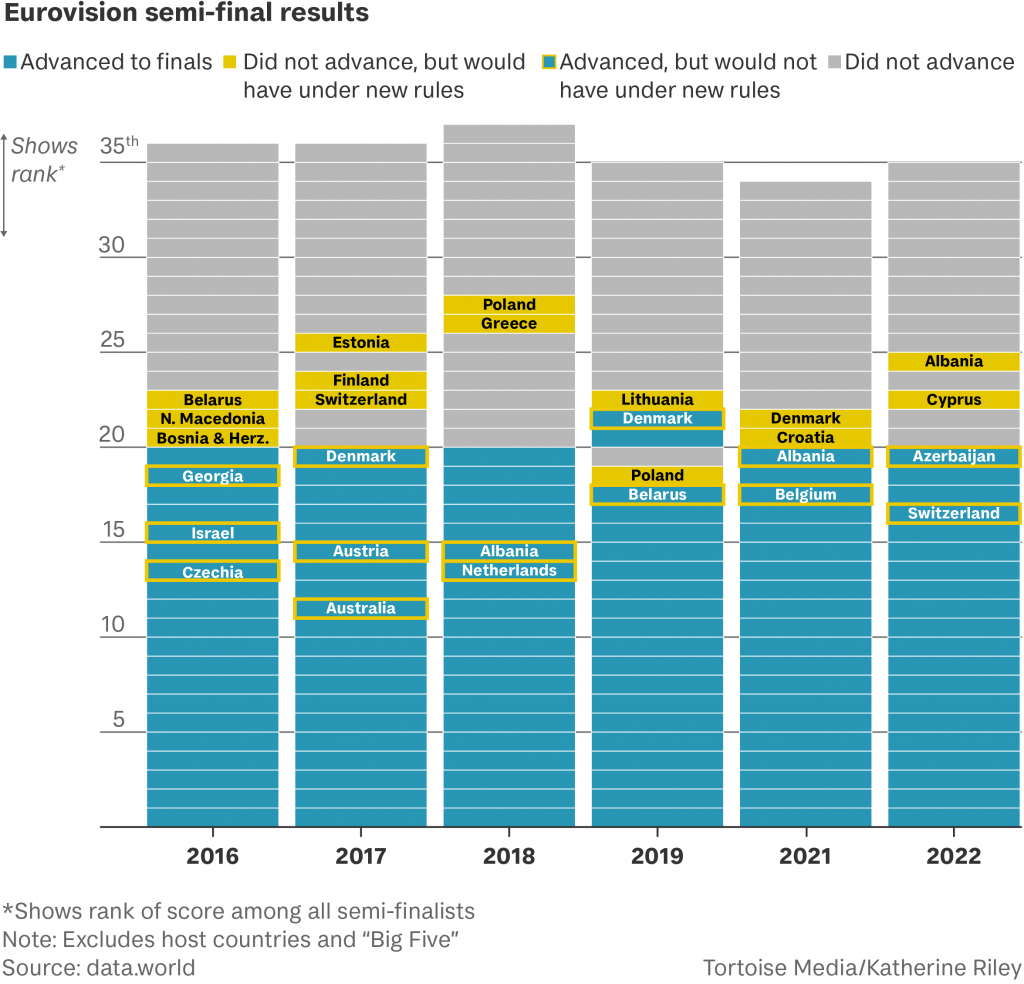

- Jury votes won’t count in the two semi-finals held earlier in the week. Instead, the public will decide via televote who should qualify for the final.

- The “rest of the world” – voters outside the EBU member countries – will be given the chance to vote for the first time in both the semis and the final.

To note: Eurovision is distinctly European, but that’s not technically a condition for entry. The EBU is a commercial organisation with full discretion over who can be a member, which is how Israel (since 1973) and Australia (since 2019) have been allowed to compete, and why technically it’s the BBC hosting next year, not the UK government.

Why it matters

Democracy. The decision to remove jury votes from the semi-finals follows six countries’ juries (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania and San Marino) being accused of “irregular voting patterns” this year – i.e. voting for each other. Dr Paul Jordan, also known as Dr Eurovision, says the jury vote “is a lot of power to put in the hands of five people” and it was “right and proper” that the EBU took action.

The music. Critics may sneer but for a significant chunk of Europe, Eurovision is one of the few chances artists have to put their music in front of an international audience. Examples of success include Abba (1974), Celine Dion (1988), Loreen (2012) and more recently Måneskin (2021) and Sam Ryder.

The money. The EBU is a non-profit organisation, but Eurovision doesn’t come cheap. It can cost between €10 million and €25 million to put on the competition. There is a contributory pot of around €6 million a year provided by the 40 or so competing nations but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its subsequent removal from the competition – which the EBU initially resisted – left a black hole in the financing. Giving the “rest of the world” a vote creates the potential for more income from digital platform rights, sponsorship and televoting.

No joke. “For some countries, [Eurovision] isn’t a joke”, Dr Jordan insists. Like Ukraine:

- In 2016 Ukraine’s act Jamala performed a song about her great-grandma’s experience as a Crimean Tatar being deported by the Soviet Union in the 1940’s.

- This year’s winners auctioned their trophy to raise money for the Ukrainian army.

- The final for Ukraine’s 2023 entry selection competition will be broadcast from a Kyiv bomb shelter.

Eurovision is the world’s longest-running annual TV music competition; a survivor of European wars, the pandemic and unprecedented changes to the broadcast landscape, with a dedicated fan base that includes a thriving LGBT+ community. It must be getting something right – something Qatar is getting badly wrong.