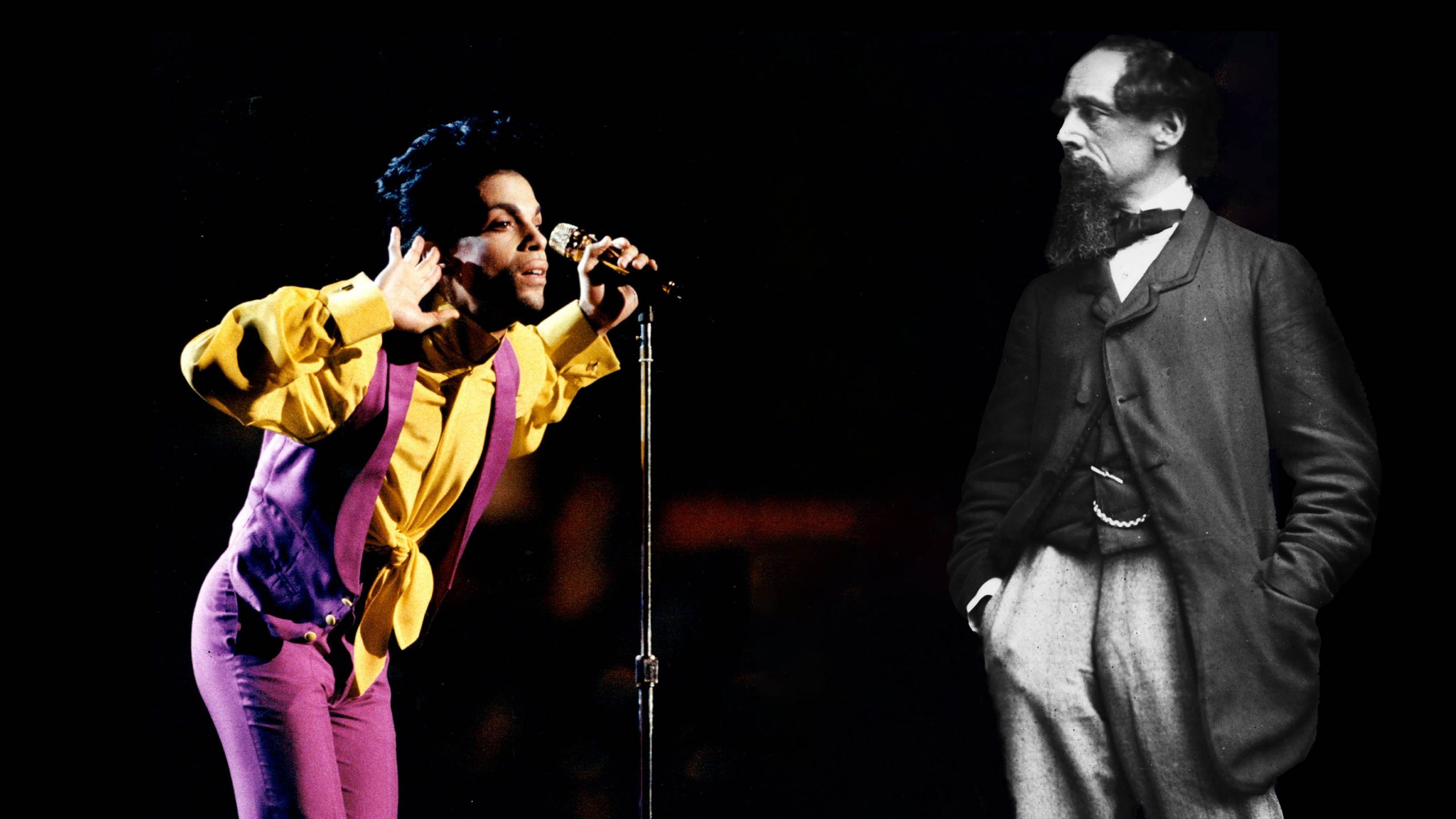

Nick Hornby’s dual study of his cultural heroes, Charles Dickens and Prince, is a fine parallel portrait of creative genius – and its mysterious origins

Gideon (Peter Capaldi), a cadaverous prisoner, sits opposite social worker Lucy Chambers (Jessica Raine). There are hints of Hannibal Lecter’s early encounters with Clarice Starling in The Silence of Lambs (1991): intimations that Lucy, no less than Jodie Foster’s Clarice, is seeking some kind of urgent insight from a man who knows all about the dark side.

That’s only the first of many allusions in the latest collaboration between producers Steven Moffat and Sue Vertue, working in this case with writer Tom Moran. Lucy has an eight-year old son Isaac (Benjamin Chivers) whose chilly emotional detachment unnerves pretty much everyone, and is being explored by Dr Ruby Bennett (Meera Syal).

Is Isaac merely distracted by paranormal forces – like Danny in The Shining (1980) or Cole in The Sixth Sense (1999)? Or is he truly possessed? And why does Lucy, beset by insomnia, keep waking up at 3:33am – the so-called “Devil’s Hour”?

In parallel to this eerie plot. Di Ravi Dhillon (Nikesh Patel) and DS Nick Holness (Alex Ferns) pursue a serial killer. In this strand of the story, the series makers have fun referring to David Fincher’s Se7en (1995) – though, as with Isaac, we wonder whether this is all misdirection, and the nature of the murders is not all it seems.

The Devil’s Hour is simultaneously mischievous and unnerving, and reveals its secrets at its own pace, across six episodes. The time jumps and entangled stories compound the viewer’s anxiety and quicken the pulse. All in all, Halloween television of a high order.

“I just don’t like you no more”: thus does Colm (Brendan Gleeson) tell Pádraic (Colin Farrell) that their friendship is over; and that he will no longer be accompanying him to the pub at 2pm, as has evidently been their longstanding daily practice.

It is 1923, on the fictional island of Inisherin off the coast of Ireland. All seems set for a whimsical melodrama of gossip and low-stakes intrigue in a tiny rural community. Pádraic, a gentle dairy farmer, who loves his donkey and interprets life straightforwardly, is puzzled by this sudden rift and Colm’s irritation with his “aimless clatterin’”. His brighter sister Siobhan (Kerry Condon) does her best to console him, whilst trying to explain to him that, in life, such things happen.

Then we recall that this is a Martin McDonagh film, reuniting him with Gleeson and Farrell for the first time since the wonderfully dark In Bruges (2008). Something deep and existential lurks within Colm’s irritation: a sense that he is wasting time, and that he will reach the end of his life having nothing to show for it, as a musician (he plays the fiddle) or a human being. He longs, as Yeats would have it, to produce “monuments of unageing excellence”, but has achieved nothing of the sort. And he is prepared to go to truly gruesome lengths to prove to Pádraic how serious is his decision.

The sound of gunfire from the mainland – the civil war between the IRA and the Free State – has been interpreted by some as a banal metaphor for the conflict between the former friends. But that is not how McDonagh writes. In his mythic imagination, the noise of violence across the water is better understood as the demons of dissatisfaction threatening the human idyll of the island. As the story progresses, Sheila Flitton’s Mrs McCormick graduates from an unpleasant elderly neighbour and nuisance to one of the Weird Sisters in Macbeth, watching and warning of imminent doom.

Gleeson and Farrell are both superb (Farrell as good as he was in The Killing of a Sacred Deer). The Banshees of Inisherin is a rare and extraordinary film that lingers in the imagination and will be remembered long after the Oscar nominations it deserves are forgotten.

In this sharp movie based on a notorious real-life case, Amy Loughren (Jessica Chastain) is an intensive care nurse at a New Jersey hospital, trying to raise her two daughters while concealing a serious heart condition from her employers (she hasn’t worked for them long enough to qualify for medical cover).

Help arrives in the form of a new and friendly colleague, Charlie Cullen (Eddie Redmayne), who quickly becomes indispensable to her professional and family life. Amy takes the risk of telling Charlie about her potentially lethal predicament.

But wait: suddenly what looks like a hospital drama becomes a police procedural, as detectives Tim Braun (Noah Emmerich) and Danny Baldwin (Nnamdi Asomugha) are called in to investigate the unexplained death of an ICU patient. To compound the mystery, the body has already been cremated. The cops are initially baffled, then increasingly suspicious that they are dealing with an institutional cover-up – and perhaps more than one.

Amy, too, begins to fret that Charlie is not all he seems. Redmayne’s descent from smooth generosity to sinuous menace is brilliantly rendered. Adapted from Charles Graeber’s book of the same name, Tobias Lindholm’s movie is rich in subtlety and all the more effective because of the understatement with which it delivers the chilling truth.

As Volodymyr Zelensky’s press secretary from June 2019 to July 2021, the journalist Iuliia Mendel was deeply embroiled in the Ukrainian president’s political life before Putin’s invasion in February. Naturally, her portrait of her former boss is generous – some have already called it partisan – though it is scarcely surprising that this is so. Nor is this memoir a hagiography: she readily admits that he has “not always been a perfect leader”, though – quite rightly – proceeds to acknowledge that “in the chaos of war he knew exactly what to do. He became our national protector.”

Much of the most interesting material in the book concerns (for instance) Zelensky’s dealings with Donald Trump and his government’s contact with the Russian autocrat: “[T]here is only one way to describe Putin: ‘old age.’ No matter how much I looked at him and his delegation, no matter how much I listened, everything about them conveyed old age: old ideology, old principles, old behavior, old thoughts.”

A native of the port city of Kherson – presently the scene of brutal fighting – Mendel is especially strong on the extent to which the conflict has cemented the resolve of Ukraine’s people to establish once and for all a sovereign independence. “We are determined,” she writes, “to restore our lost Ukrainian heritage while we also construct a vibrant contemporary identity. We have plenty of ideas about where we are headed, what we value from the past, and who we will be in decades to come.”

There will be many more books about this war, but Mendel’s should bolster the determination of the West to stick with Ukraine at all costs, for as long as it takes. How embarrassingly petty seem recent political upheavals at Westminster when one reads her description of a war that “has burned away all that was artificial and superficial in our lives.”

Did you know that James Bond’s middle name is Herbert? Craig Brown does. He knows almost everything else, it seems; fuelling the great engine of his humour that magnificently powers through this wonderful collection of his writings in Private Eye, the Daily Mail, the New York Review of Books and other publications.

So he is able to explain just why the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup (1933) is as funny today as it was nine decades ago: “Everything has been transformed into something else. The world has become a pun.”

With no less panache, he can imagine the diary of Jacob Rees-Mogg: “The breaking of one’s fast, or to employ the dreadful modern jargon, ‘breakfasting’ (!) with one’s family is surely one of the of the great pleasures of existence on earth.” Or describe how Kim Jong-Un would explain his appearance on Piers Morgan’s Life Stories: “You know what, Piers? I feel I owe it to my fans. They’ve been with me through the good times and the bad.”

His memories of Peter Cook are riveting: “the High Priest of Boredom, the Town Crier for Laziness… If only his jokes had been less funny, Peter Cook might have been rated the equal of Pinter and Beckett, perhaps even their superior.” But he is no less interesting on David Bowie, or Bruce Springsteen, or Keith Richards (who, he writes, performs for a certain generation the same role that the late Queen Mother did for its forebears: “a symbol of stability, the embodiment of easy living, a reminder, in these uncertain times, that some things never change”). A must-read anthology by a writer of almost preternatural versatility.

“Pascal’s Wager is often described as the calculation that we should believe in God as, on the off chance that hell is real, doing so will save us from eternal damnation. That isn’t false; it also isn’t the full story. There is a third part: if you pretend to believe in God long enough, over time you will actually have a true belief in God. What was once a story you went along with will eventually become your reality.

Strangers to Ourselves, the debut book by New Yorker staff writer Rachel Aviv, is about how that last stage – the power of the stories we tell ourselves – interacts with the field of modern-day psychiatry. A mental health diagnosis is taken by many to be a neutral thing, a description of ailments. But Aviv claims this isn’t the case – a diagnosis is just a narrative about someone’s identity, and often not a fully accurate one at that. As a narrative, it has the power to shape future identity; Western medicine often overlooks this power, to its own detriment.

That our identity is shaped by stories isn’t a particularly new idea. But that’s fine. Read this book not for its originality, but because Aviv shows precisely how stories intertwine with identity better than anyone else. How narratives work in conjunction with self-identity is tricky; it’s neither a fully internal or external process. How we view ourselves is shaped by the outside world, but how we view the outside world is undeniably linked to how we view ourselves.

Aviv uses six case studies as her framework for elucidating this complex interaction, allowing the narratives to speak for themselves. To explain how stories function she prioritises the story itself, allowing her to show – and not abstractly tell – precisely how the complex interaction between narratives and self-identity functions.

The end result is a book not so much about the failure of Western psychiatry as the inaptness of universals. We tell ourselves stories about ourselves, but no story is the story. Failure to comprehend that, Aviv shows, is just about as destructive to the mind as anything in the DSM-V.”

Sixteen years have passed since Alex Turner and his fellow band members barged their brilliant way into the mainstream with Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not – an album that drew its title from Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958). Remember Gordon Brown getting himself tied in knots by suggesting that he knew who the Arctic Monkeys were?

Like, say, Elvis Costello or Paul Weller, they have refused (admirably) to be trapped by their first contact with success and have continued to evolve and explore musical styles; most notably with their 2013 masterpiece AM.

In The Car, the band audaciously embraces the spirit of Burt Bacharach, the Rat Pack and lounge music, across ten tracks that positively relish lush orchestration and an 18-piece string section. The overall effect is noir-ish – ‘Hello you’ includes an explicit reference to Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye (1953) – the smoothness and apparent confidence of the sound undermined by the paranoia and unease of Turner’s lyrics.

Never far from his thoughts is the response of some critics and fans to the way in which the Monkeys have changed over the years; “puncturing your bubble of relatability with your horrible new sound”, as he puts it on ‘Sculptures Of Anything Goes’. On the same track he asks archly: “How am I supposed to manage my infallible beliefs?”

On “Jet Skis on the Moat”, he juxtaposes the perks of the big time with the flatness of reality. “Are you just happy to sit there and watch while the paint job dries?” Which is not to say for a second that the band has lost its sense of fun and raucous wit. And how could anyone possibly dislike an album that included the line “Lego Napoleon movie written in noble gas-filled glass tubes underlined in sparks”?

When it comes to classical duet albums, it makes all the difference when the performers are good friends. Witness, for instance, the great tenor-baritone double act of Plácido Domingo and Sherrill Milnes.

Conducted by Sir Antonio Pappano and accompanied by the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Ludovic Tézier and Jonas Kaufrmann have produced a superb recording that showcases not only their respective virtuoso talents but also the creative power of camaraderie in such collaborations. Kaufmann says that “with this guy if you don’t go full throttle, you’re lost”; the baritone Tézier returns the compliment, observing that they strive, in their musical partnership, “to try and create a third voice”.

Last year, Kaufmann played Parsifal opposite Tézier’s Amfortas at the Wiener Staatsoper – both daunting parts – and the ease they have have developed together as performers is triumphantly evident in this collection of duets from Puccini’s La Bohème, Ponchielli’s La Gioconda, and (natural terrain for Pappano) the operas of Verdi. The Don Carlos and Otello duets are especially successful, full of drama and tension. The two father-son duets from Les vêpres siciliennes are beautifully realised, too.

“Hi my name is Phoebe and I am a Swiftie – it’s taken a while for me to be out and proud about being a devotee of Taylor Swift. It’s a silly thing really; there is an army behind me. Swift’s new record, Midnights, became the first album for five years to clock up a million units in a week. The last album to achieve this? Her 2017 record reputation.

I had, with regret now, stuck up my anti-mainstream nose at records like reputation. But the stars aligned when she released her pandemic albums folkore and evermore in rapid succession in 2020, featuring production from Aaron Dessner of the National, the Haim sisters and Bon Iver – artists I have huge respect for. Those albums distinctly broached the folk-rock genre I was comfortable with, while remaining true to familiar Swift topics: i.e. breakups and love. I was hooked. Her re-release of Red in 2021 – timed, as Swift would have intended, with my own breakup – sealed the deal.

It’s with all of this that in mind I plunged into the heady, hazy fog of Midnights – her tenth studio album. The 13 tracks, a well-documented number in Swiftian lore, are a delight that crowns her already solid place in pop royalty. It is more produced than her previous releases – she worked heavily with Jack Antonoff, a marmitey sticking point for some fans. But its steady drumbeat of sparkling synths and yearning vocals bring us closer to her pre-pandemic, pre-Scooter Braun, pre-Kanye drama work. Stand out songs are ‘Labyrinth’ and ‘Midnight Rain’.

There are some tracks that feel a little heavy in production, including ‘Snow on the Beach’ with Lana Del Rey. It’s also clear that this is a record designed for stage performance: something that was not true of folklore and evermore (not to their detriment). Still, her surprise appearances on Haim and Bon Iver’s respective tours show she isn’t quite ready to drop that style yet.

But the real joy of Midnights lies in the absolute mayhem of her 3am tracks, seven bonus songs that didn’t feature in the epic social media run up to the album. Bringing back Dessner to produce, they are, in the opinion of this Swiftie, some of the best tracks of her career. ‘Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve’ is the reason I will shell out money and time to fight off other fans for her upcoming tour tickets.”

“Having debuted with a sold-out run at The Turbine Theatre in 2021, My Son’s a Queer (but What Can You Do?) is an unabashedly queer and over-the-top portrayal of writer and solo performer Rob Madge’s theatrical childhood. When Madge was 12, they roped their parents and grandma into staging their own full-blown Disney parade, right in their Coventry living room.

Packed full of childhood nostalgia and tapes from their parade, My Son’s a Queer tells the story of Madge growing up different, coming to terms with their identity, and of course recreates that parade, albeit with a bigger budget. It is no wonder that the show was crowned Best Off-West End Production 2022 at this year’s WhatsOnStage awards – it is a show for everyone, regardless of background, who has ever been made to feel ashamed for simply existing and being themselves.

The stripped-back set and costume design, courtesy of Ryan Dawson Laight, creates a perfect backdrop of Madge’s living room, allowing their stellar performance to shine through. It isn’t an easy task to carry a one-person show by yourself, let alone one complete with half a dozen fully choreographed musical numbers – which makes Madge’s performance all the more special. Not only do they capture the joy and excitement of putting on their own Disney parade, they manage to weave in their heart wrenching journey of self-discovery and coming to terms with their identity as a non-binary person.

With lyrics that will move you to tears and have you burst into fits of laughter in the same line, My Son’s a Queer so accurately captures the experience of anyone who felt different growing up, without apologising or toning down Madge’s exuberant personality.

My Son’s a Queer (but What Can You Do?) runs at the Garrick until Sunday 6 November. Tickets are available here.”

Don’t forget to send in your own recommendations for Creative Sensemaker to editor@tortoisemedia.com.

That’s all for now. Enjoy the weekend and take care of yourselves.

Best wishes

Matt d’Ancona

Editor and Partner

@MatthewdAncona

Photographs Getty Images (digital composite Tortoise Media), LGI Stock/Corbis/VCG, Kevin Fleming/Corbis, Netflix, Amazon Prime, Mark Senior

Sponsored by