William Gibson, the master of cyberpunk and high-tech speculative fiction, at last gets a screen adaptation worthy of his work, in a spectacular new series starring Chloë Grace Moretz.

Four decades have passed since William Gibson coined the term “cyberspace” in the short story Burning Chrome (1982) – a full seven years, please note, before Sir Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, and more than twenty before high-speed broadband became widely available.

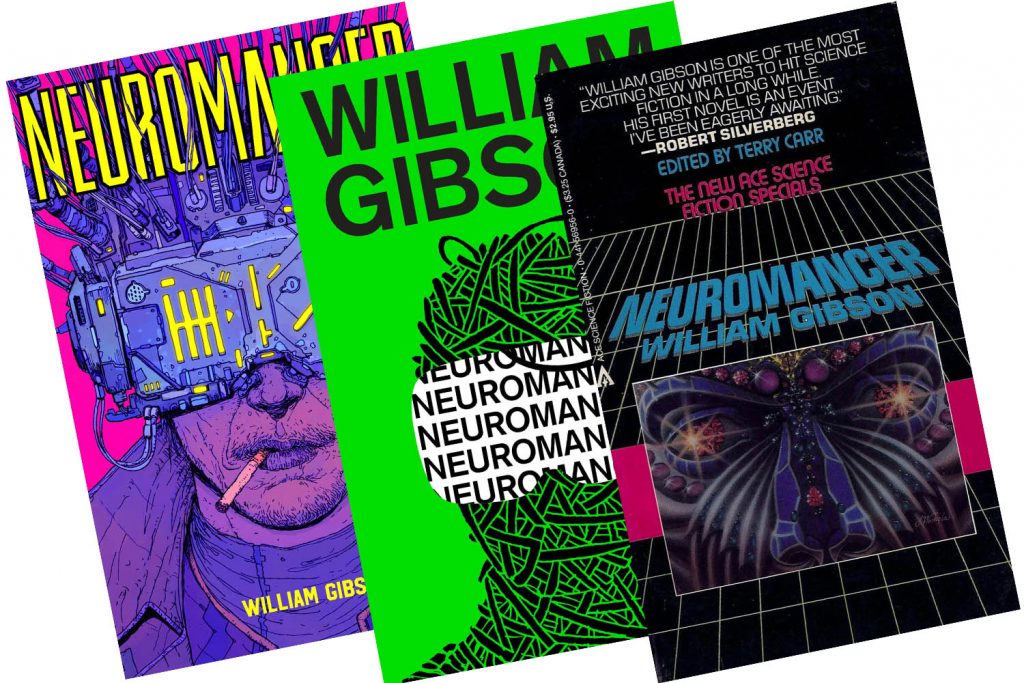

The word went on to be popularised globally by the founding text of the “cyberpunk” genre, Gibson’s debut novel Neuromancer (1984), which has sold seven million copies and is the only book to have won the Nebula, Philip K. Dick and Hugo Awards.

In this classic of high-tech adventure, full of hackers, hustlers, ninjas, AI entities, mercenaries, and corporate warriors – much of it set in the Japanese underworld – the author defined cyberspace as “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts… A graphical representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the non-space of the mind, clusters and constellations of data”.

But here’s the thing. Having come up with a word that so well described the way in which information technology was about to transform the world, Gibson has long since relegated it to the category of “heritage” terminology.

As he put it in 2002, the partition between what we call “real life” and what he had previously called “cyberspace” is now so blurred as to be meaningless. In practice, we had already become cyborgs, flesh-and-blood beings completely integrated with an automated network of unfathomable potential: “We tend not to see it because we are it, and because we still employ Newtonian paradigms that tell us that “physical” has only to do with what we can see, or touch. Which of course is not the case. The electrons streaming into a child’s eye from the screen … are as physical as anything else. As physical as the neurons subsequently moving along that child’s optic nerves. As physical as the structures and chemicals those neurons will encounter in the human brain. We are implicit, here, all of us, in a vast physical construct of artificially linked nervous systems. Invisible. We cannot touch it. We are it.”

This is one of the principal philosophical premises underpinning his 2014 novel The Peripheral (and its 2020 sequel Agency) which has now been compellingly dramatised in an eight-part series streaming on Prime Video from 21 October. Based in two locations and two time-frames – the Blue Ridge Mountains in 2032 and London in 2099 – the story follows Flynne Fisher (Chloë Grace Moretz), a gamer who plays for money, as she travels, using an advanced prototype headset, into a virtual world that starts to feel all too naturalistic.

Looking after her sick mother, Ella (Melinda Page Hamilton), and fretful about her Marine veteran brother Burton (Jack Reynor) – still troubled by the “haptic” implants installed by his military masters – she works by day in a 3-D printing shop. Encouraged by her friend Billy Ann (Adelind Horan) to make more of her gaming talents, Flynne shrugs off the notion: “It ain’t real. And, like it or not, this is the only world I got.”

But what if this particular game is real (depending upon your definition of that hotly contested world), and her 2032 life and the supposedly imaginary London of 2099 – a gleaming city full of towering statuary, where corporate parties are held at Buckingham Palace – start to become entangled and intimately interconnected?

To say much more would be to spoil a twisty, gripping tale that is firmly rooted in Gibson’s original novel but not hidebound by its precise form or content. The dual aesthetic – Appalachian grit versus future techno-London – is superbly managed by show-runner Scott B Smith, especially as the tendrils of the two worlds start to intertwine.

Worth noting: this is emphatically not just another variant on The Matrix series: the questions posed by The Peripheral – which takes its name from a particular class of avatar – are only intellectual cousins to those explored by the Wachowski sisters. Also worth noting: the series, like the novel, immerses itself in the mutating architecture, history and spirit of London (the first episode ends with London Calling by The Clash, a band that Gibson has always loved).

The series certainly brings to a triumphant end the jinx that has always seemed to afflict adaptations of his work. Johnny Mnemonic (1995), based on a 1981 short story, has Keanu Reeves going for it – and just about nothing else. Abel Ferrara’s New Rose Hotel (1998), inspired by a Gibson story first published in 1984, has a stellar cast (Christopher Walken, Willem Dafoe, Asia Argento, Annabella Sciorra), but still manages to be truly terrible.

A clue to the failure of these sci-fi cinematic projects and of their respective directors to understand the true spirit of the author’s work is provided by the only Gibson movie that has succeeded to date: Mark Neale’s No Maps for These Territories (2000), a documentary road trip film, featuring the author sitting in the back of a car, discussing his work and ideas (for a more recent primer on his thinking, try Conversations with William Gibson, edited by Patrick A. Smith).

Looking back on his migration to Canada from Virginia in 1967 (mainly to avoid the draft), his experience of the counterculture in Toronto and then his move to Vancouver where he lives to this day, Gibson explains that he sees himself neither as prophet nor, in the traditional sense, as a science-fiction writer. “It’s just happening.” he says. “We’re in something here. And it’s out of control.”

He worries less about the future than most people, he continues, because he understands that it is both unknowable and beyond human management. Technology, as he sees it, does not submit to “legislative change”, and so triggers in all of us “these moments which are vertiginous and terribly exciting and frightening… and I think it induces fear and ecstasy.” As a consequence, we are, Gibson reckons, always at least ten years behind any informed sense of the rapid-fire changes that are coursing through human existence and of what they mean.