When it comes to murder mysteries, Lynne Truss knows not only who did it, but how to do it

How do crime writers do it? How do they make the plots come out perfectly, with all loose ends tied up, and a satisfying denouement? Do they cunningly work backwards from the solution? Do they consult helpful how-to books by Patricia Highsmith or Elizabeth George? Or is there perhaps a simple secret formula, known only to the celebrated members of (say) the select and august Detection Club?

Having spent the past few years writing mysteries, I have concluded that the best analogy for writing a decent plot appears in Stephen King’s fabulous book On Writing. I recommend it to anyone considering authorship. King demonstrates with honesty that story-telling is a craft that can be learned. But what he says about plots is perfect. He says that writing a good plot feels like excavating an archaeological find.

No doubt I have adopted and adapted this insight, because in my own experience the excavation analogy holds true. What happens regularly to me is that I notice a small fragment sticking up out of the sand and I think, “That’s intriguing”. I look at it for quite a long time, wondering what it is and what’s beneath. Then I start writing, and brushing away the sand, carefully, to reveal a bit more. And if what I continue to find is not only intriguing but surprising (and apparently intact), I keep brushing and trowelling, to unearth more and establish an outline, and in no time I am completely absorbed in trying to get the whole thing out to the light of day.

I suspect this isn’t helpful to everyone, because it can’t be taught, and it sounds airy-fairy. And of course it can only work if the underlying mechanics of story-telling are understood. I believe that so-called “story structure” is instinctive to all of us, but it can certainly be broken down and explained. In the 1990s, it was prescriptively taught by the self-appointed guru Robert McKee: for a while, every clued-up writer in the English-speaking world constructed their plots in three acts and a coda just because McKee had told them to. Rather more worryingly, all editors of films and books rejected stories that weren’t told in three acts and a coda for related slavish reasons. But it’s true that stories do unfold according to certain rules, which are all in the service of keeping the reader (or cinema-goer) intrigued and engaged moment to moment, while dangling the promise of enlightenment and satisfaction at the end.

In the past few years I’ve been writing crime novels – comic crime novels, just to make things harder; moreover, comic crime novels set in the past. There is an element of writerly grandstanding to this sort of endeavour, and you would naturally suppose that for my own peace of mind there would be a plot firmly in place before the first word was set down. But as my enthusiasm for Stephen King’s excavation analogy will already have indicated, I am not one of those novelists who work out their plots in detail in advance, because for better or worse I regard writing and inventing as the same activity. I can’t do all the inventing first, and then get down to the writing. I would honestly rather kill myself.

As for those underlying mechanics, I did attend a Robert McKee course, years ago. It took place over a long weekend in London, and ended with an all-day, shot-by-shot analysis of Casablanca. It gave me the worst headache I’ve ever had, and I found McKee insufferably self-important, but I suspect a lot of what he said sank in. However, a career in journalism and radio has helped me just as much, I suspect. As I write a story, I am always asking myself, “At this point, what do we readers know?” and “At this point, what must we readers know next?” If new background information is required, then I must come up with it. And come up with it I do, with pleasure, because new background stuff nearly always throws up suggestive narrative points to be revisited later. I often think of the opening of Dickens’s David Copperfield: the business of David being born with a caul. Right at the outset, Dickens (as David) stops to tell us the price paid for the caul and who bought it, and the admiring reader thinks, “How rich is Dickens’s imagination!” But it’s cleverer than that. Dickens is setting out David’s stall as an author himself – an author, moreover, with supreme writerly instincts. Even when writing about himself as a babe in arms, this man won’t waste a single opportunity to lay down detail that might be a) entertaining, b) arresting, or c) come in handy later on.

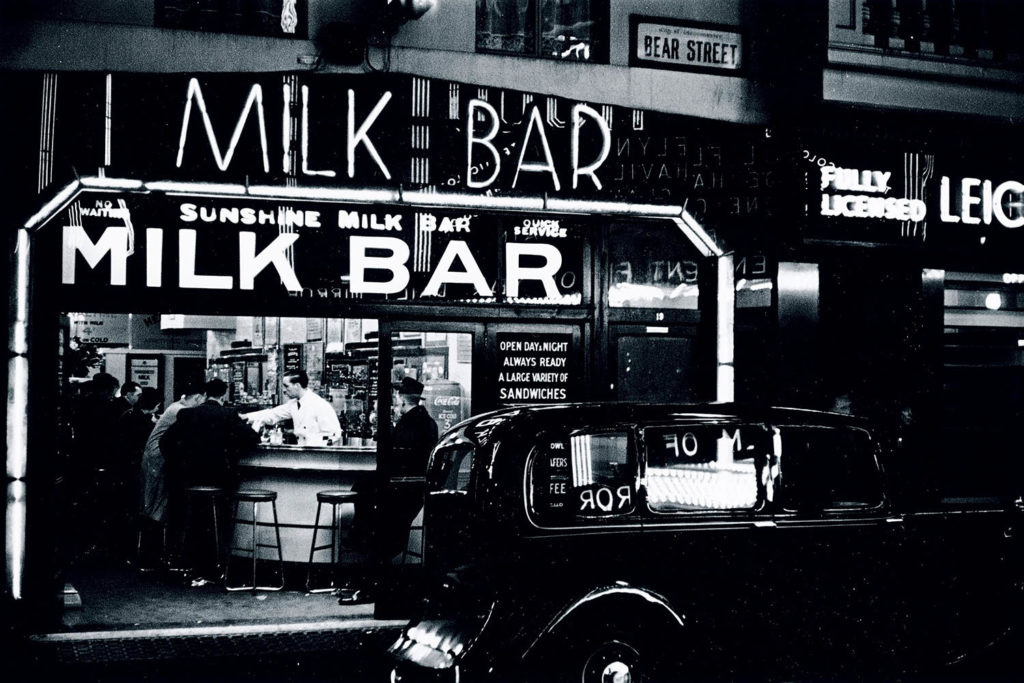

An example is required. All this theory needs to be illustrated. So I will take my third “Constable Twitten” novel, Murder by Milk Bottle. Did I have the title, at least, when I began this book? The answer is no, not immediately, but I had researched Brighton in 1957, which is the backdrop to all my crime novels, and had been struck by the enormous and strange amount of milk marketing going on. According to the local press, Brighton was awash with dairy queens and milk-float parades; a small herd of cows was kept for a while in the Pavilion Gardens; a person known just as the “Milk Girl” featured on huge posters; milk bars were proliferating; milkman jokes were in their heyday; meanwhile, the famous slogan drinka pinta milka day was being actively dreamt up by the seemingly all-conquering Milk Marketing Board. Reasonably enough, I decided on a milk theme, which would serve two purposes: it would be authentic to the period and also a bit disgusting to modern sensibilities. Along the way I unfortunately discovered the catchy 1930s song “Let’s Have a Tiddley at the Milk Bar”, which became a total ear-worm, but that’s another story.

So I started the book. It is the Friday before the Bank Holiday weekend of August 1957 and the three policemen of the series – young, keen Constable Twitten; jaded Sergeant Brunswick; famous and self-satisfied Inspector Steine – are engaged in a variety of early-evening activities. Twitten visits an AA control man in an office on the seafront, because he wants a break from investigating the ghastly multiple murders of the previous two books. Brunswick waits for a date with a beauty queen contestant outside the SS Brighton – a huge (now long gone) venue for ice shows in West Street. Steine finds himself roped in to a radio quiz broadcast live from the Dome Theatre, which he typically hasn’t prepared for. And that evening, what happens crime-wise? Well, quite a lot. An AA patrol man is found dead, killed with a milk bottle. The beauty queen fails to show up, having been killed at a children’s playground, also with a milk bottle. And the vilest of Steine’s fellow contestants in the quiz is – you guessed it – killed with a milk bottle in an alley behind the theatre.

Now, I know your first question. What did these three people have in common, and who disliked them all enough to kill them? This was my first question, too. Why a milk bottle? was also a pressing concern. I knew that the ice show must be part of the plot; likewise the playground; likewise the cows in the Pavilion Gardens and the Milk Girl. So I pressed on, quickly bringing in the Milk Girl in the form of the 19-year-old Pandora Holden, who had a history involving Twitten. And on top of all this, my fourth regular character, the criminal mastermind charlady Mrs Groynes, needed to have her own equally important plot concerning an August Bank Holiday gathering of top villains at the Metropole Hotel. All these elements had to weave together, so that eventually we would discover who killed three people with milk bottles, and the song “Let’s Have a Tiddley at the Milk Bar” would incidentally get its spotlight moment along the way.

Is this revelation helpful? Or is it just disappointing? At least it’s honest. In my defence, if I didn’t have the whole plot in my head to begin with, I did know the structure of the book, and I stuck to it. Once I had decided to make the Milk Girl a character, I knew I must devote a whole chapter to her back-story – including her history with Twitten and her school days at a famous cliff-top girls’ school (which proved significant). I hugely enjoyed creating the solipsistic Pandora, by the way, not just because she provided a kind of nagging love interest for my main character, but because her adamantine self-regard was a means to set down certain unkind thoughts about a real person in my life who was, at the time, rather a bugbear. You will say that this was pathetically passive-aggressive, and also an abuse of the writer’s privilege. To which I reply: you bet.

Crime writing is a broad church. There are umpteen ways to write a satisfying crime story. Personally, I want the reader to engage with my characters to such an extent that the plot seems to take care of itself, and I’m always dismayed by novice reviewers who go into exhaustive plot detail (honestly, who cares?) when they could instead be saying how enjoyable the book is. But heigh-ho. Rewriting is of course important: each book goes through about six drafts before I’m sure that everything adds up. The plots always work, and it’s important to me that the denouements are surprising but also inevitable – which of course should be the case in all stories, not just crime ones.

The plot-excavation method might not suit everyone, but it has three significant comforts. For one thing, since I am choosing to assume that my plot already exists below the surface, I can dig with confidence. Second, if inventing and writing go hand in hand, there is bound to be a creative energy in the writing that can’t be faked. And lastly, I never have to worry that the reader will guess the ending in advance. If I, as the writer, don’t yet know who did it, then the reader can’t possibly get there ahead of me, can they?

Lynne Truss is a journalist and writer. Her most recent novel, Psycho by the Sea, is the fourth instalment in the Constable Twitten series about a case-cracking policeman in Brighton. She also wrote Eats, Shoots & Leaves, the iconic book about punctuation.

This piece appeared in the latest edition of the Tortoise Quarterly, our short book of long stories. If you were lucky enough to grab a Founding Membership back in the early days of Tortoise, you’ll receive your copy in glorious, old-fashioned print. If not, you can pick up a physical copy in our shop at a special member price.

Illustrations Cristóbal Schmal

Photograph Getty Images