The Budget isn’t until 30 October but Rachel Reeves already has her mind made up. Today the UK’s chancellor must submit her plan for tax and spending to the OBR, so it can build a forecast. Speculation is mounting that it will include a technical change to the UK debt rules to increase national borrowing.

So what? It’s not just technical. This is a government-defining decision on

- the role of the state;

- how to grow the economy;

- how much of that depends on capital investment; and

- how much of that should be funded with debt.

It’s the culmination of a long campaign to reposition “borrowing for investment” – the sell of Reeves’ party conference speech – as the only plausible solution to the UK’s crisis of productivity. It has a number of big name supporters, including:

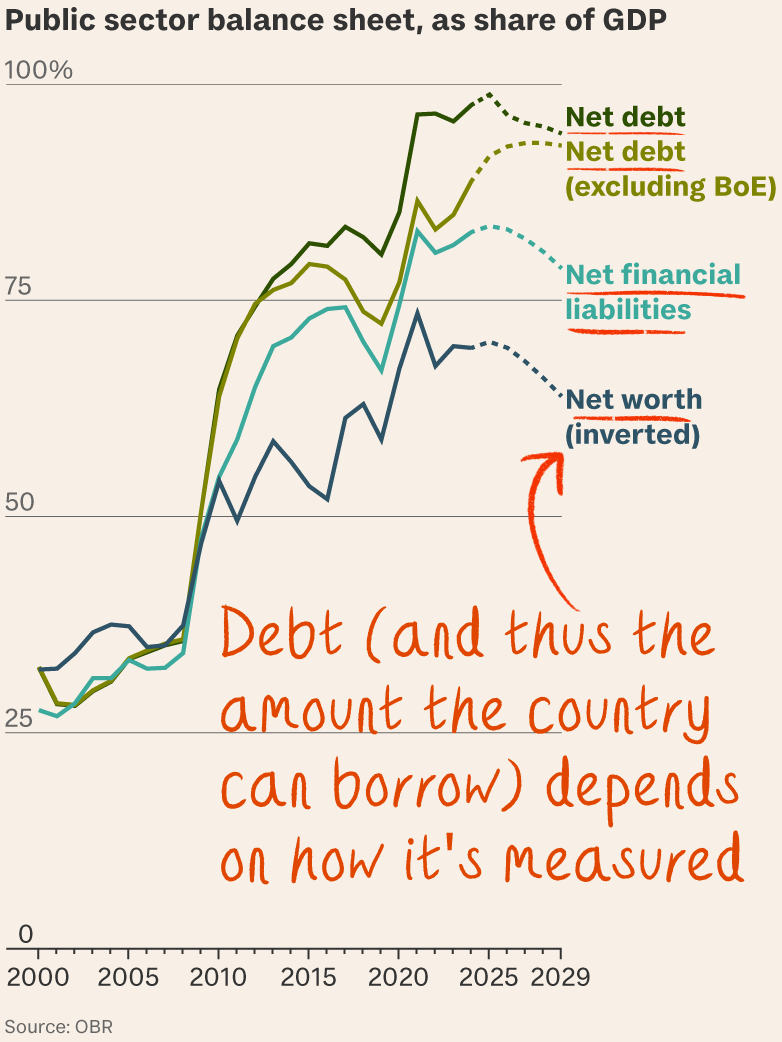

- The IMF, which says traditional anchors of fiscal policy such as “gross debt” aren’t conducive to investment, and should be replaced by metrics like “net worth” (see below).

- The IPPR, a think tank which advocates tinkering within the UK’s rules to unlock £57 billion of additional investment, with some held back as a buffer.

- Pension funds managing £1.7 trillion of assets whose bosses say the current framework discourages investment in infrastructure projects.

- Gus O’Donnell, the former cabinet secretary, who has urged Labour to ditch the last government’s “absurd” rule which requires debt to be falling within four to five years but says nothing about before or after that point.

Pros and cons. Debt service costs – already at 7.3 per cent of public spending – would go up, but so, in principle, would growth.

What’s on the table? In her quest for more fiscal headroom Reeves has three major options (and acronyms) to play with:

- PSND. Public sector net debt is how the government currently measures its fiscal position. But PSND counts losses incurred by the Bank of England due to higher rates. Changing it to a headline measure would ease pressure on the falling 5-year debt target and probably wouldn’t spook investors. Extra cash: £16 billion.

- PSNFL. Public sector net financial liabilities is a measure that counts the financial benefits (and debts) of future investments. For example, it would include the revenue accrued by the government from students repaying their loans. Extra cash: £53 billion.

PSNW. Public sector net worth is similar to the above but includes counting the value of government-owned non-financial assets, such as prisons (not an easy item to price), against its debt. Extra cash £57 billion.

What’s the risk? Investors could baulk as they did under Truss in September 2022. UK gilt yields, which go up when investors offload government debt, have climbed from 3.75 per cent to around 4.2 per cent in the last three weeks. Sterling’s rally has gone into reverse and UK consumer confidence fell sharply in September. Reeves is delivering the red box in a fragile economic environment.

Markets don’t like sleights of hand, but they do like long-term investments that deliver returns. Much will depend on how a potential rule change is packaged and communicated. If the government chooses to adopt a “net worth” measure, it would be advised to hold some of the extra spending power for a rainy day (or the next government). Financial returns tests could also reassure investors.

What could it pay for? While national debt has climbed over the last 25 years, public assets have barely grown, with the result the UK is more “in the red” than any other rich country except Portugal. A study by the OBR found that a public investment of 1 per cent of GDP breaks even after about ten years, and in fifty would deliver a return of 2.5 per cent of GDP. A version of the national accounts that looks beyond five years and recognises that many investments pay for themselves might be the right kind of growth incentive. The biggest bang per buck is to be found in sectors like energy, transport and other revenue-linked infrastructure.

What’s more… The UK has pioneered the development of fiscal rules and was one of only 19 countries to adopt them when Gordon Brown first introduced his in 1997. Targeting “net worth” rather than “net debt” would be another first.