When Trump claimed in Tuesday’s presidential debate that “In Springfield, they’re eating the dogs”, it wasn’t a reference to the Simpsons episode in which Homer drinks beer brewed with dogs. It was a piece of disinformation that originated in a local Facebook group based in Springfield, Ohio.

The post claimed that Haitians living in the city were abducting and eating family pets. It was false, attention-grabbing and made its way to X, where it was amplified by X’s owner, Elon Musk. Then came Tuesday. “THEY’RE EATING THE DOGS” quickly went viral on the platform, thanks mainly to gleeful Trump opponents. Perhaps they should temper their joy.

Millions have spent the past two days discussing a little-known city which Trump supporters present as a symbol of failed Democratic immigration policies, to an audience now paying attention. Undecided voters may not believe the canine claim, but they could be thinking about Springfield.

Back in July, Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, described Springfield as “nearly a carbon copy” of the place where he grew up. He said Springfield’s population had increased by 20,000 in recent years and that this was due primarily to an influx of Haitian immigrants. (The official Springfield website puts the total immigrant population in the county at 12-15,000.)

Vance neglected to mention that this influx has arrested a sharp fall in the population of Springfield since the 1970s and is designed to revive its struggling economy. Most of the immigrants have temporary protected status and work permits, having left a country brought low by gang violence, natural disasters and a series of political crises.

Springfield’s population increase has created problems. Data from the property site Zillow shows that since 2022 rents have accelerated much faster there than in the rest of the US.

What it hasn’t caused, according to Springfield city officials, are any “credible reports or specific claims of pets being harmed, injured or abused by individuals within the immigrant community”.

The origins of Trump’s baseless claim seem to be an 8,000-strong private Facebook group called Springfield Ohio Crime & Information, in which a woman cited a neighbour who claimed her daughter’s friend’s cat had been abducted and hung from a tree by Haitian residents, in order to be eaten. “I’ve been told they are doing this to dogs,” the woman added.

Other claims about Haitian immigrants were also made at a Springfield City Commission Meeting on 27 August. Speakers included a man who identified himself by a racist pseudonym and said he was from a neo-nazi group, Blood Tribe, which had recently marched on the city waving swastika flags. Four days before the debate, Blood Tribe posted on Gab, a social media platform popular with the far-right: “Sorry Springfield, you’re just going to have to get used to the idea that your neighbors might eat your pets.”

It was when the disinformation hit X that it exploded. The first widely-seen post was by an account called End Wokeness on 6 September. It shared a screenshot of the original Facebook post alongside a picture of a person of colour holding what appeared to be a dead goose.

The post has had just under 5 million views on X and hasn’t been flagged as misinformation, despite the fact that the accompanying photo was taken in Columbus, a different city in Ohio. There’s no evidence that the man pictured is from Haiti or was planning to eat the bird he was carrying. Other posts sharing disinformation about Springfield conflated it with an arrest video of an Ohio woman accused of killing and eating a cat. The woman was arrested in Canton and is believed to be a US citizen with no known connection to Haiti.

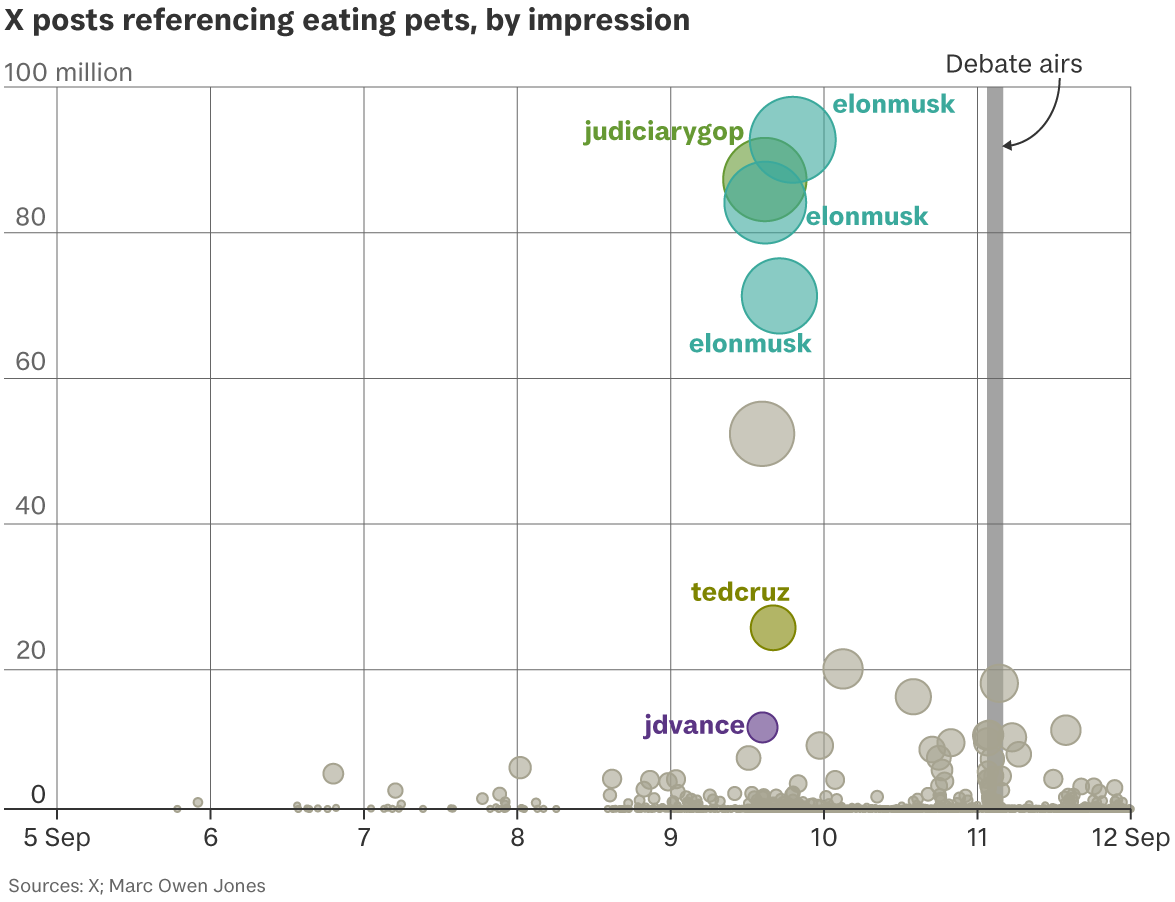

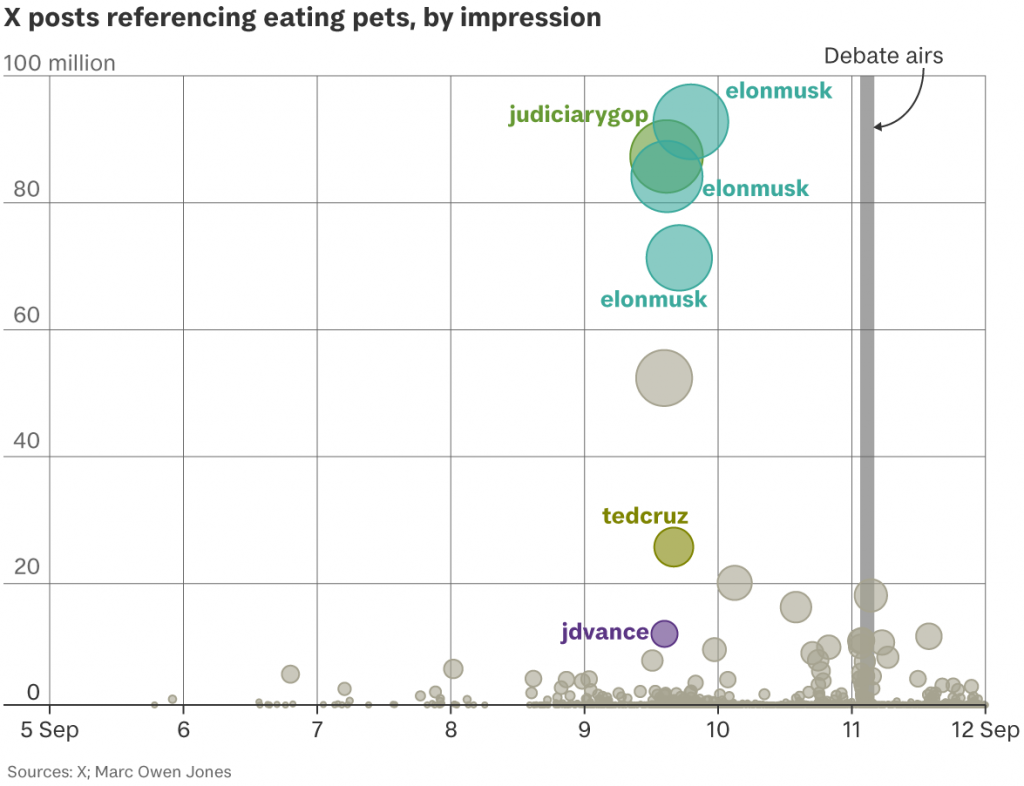

Data shared with Tortoise by the researcher Marc Owen Jones shows that the most-viewed tweets amplifying the Springfield disinformation came in the hours before the presidential debate. They include three Elon Musk posts, and tweets from Vance and the Republican House Judiciary account. “Musk put it on the agenda,” Jones says.

But it was when Trump himself referenced the claim that the floodgates opened in terms of posts on Springfield and coverage of the city in the media.

No matter that many of the posts and pieces were written to debunk the disinformation. “It’s like when you put a question in the headline of a newspaper article,” Jones says. “The important thing is not the answer but the headline.

“Most people will remember Haitians, immigrants, and pets, and not necessarily think about whether that was true or not. Creating associations is half of what disinformation is.”

On Wednesday an AP headline, without any mention of Trump’s comments a day earlier, read: “Ohio is sending troopers and $2.5 million to Springfield – a city that has seen an influx of Haitian migrants.”

If JD Vance cited Springfield back in July to increase the salience of immigration as an election issue, this week he belatedly succeeded.