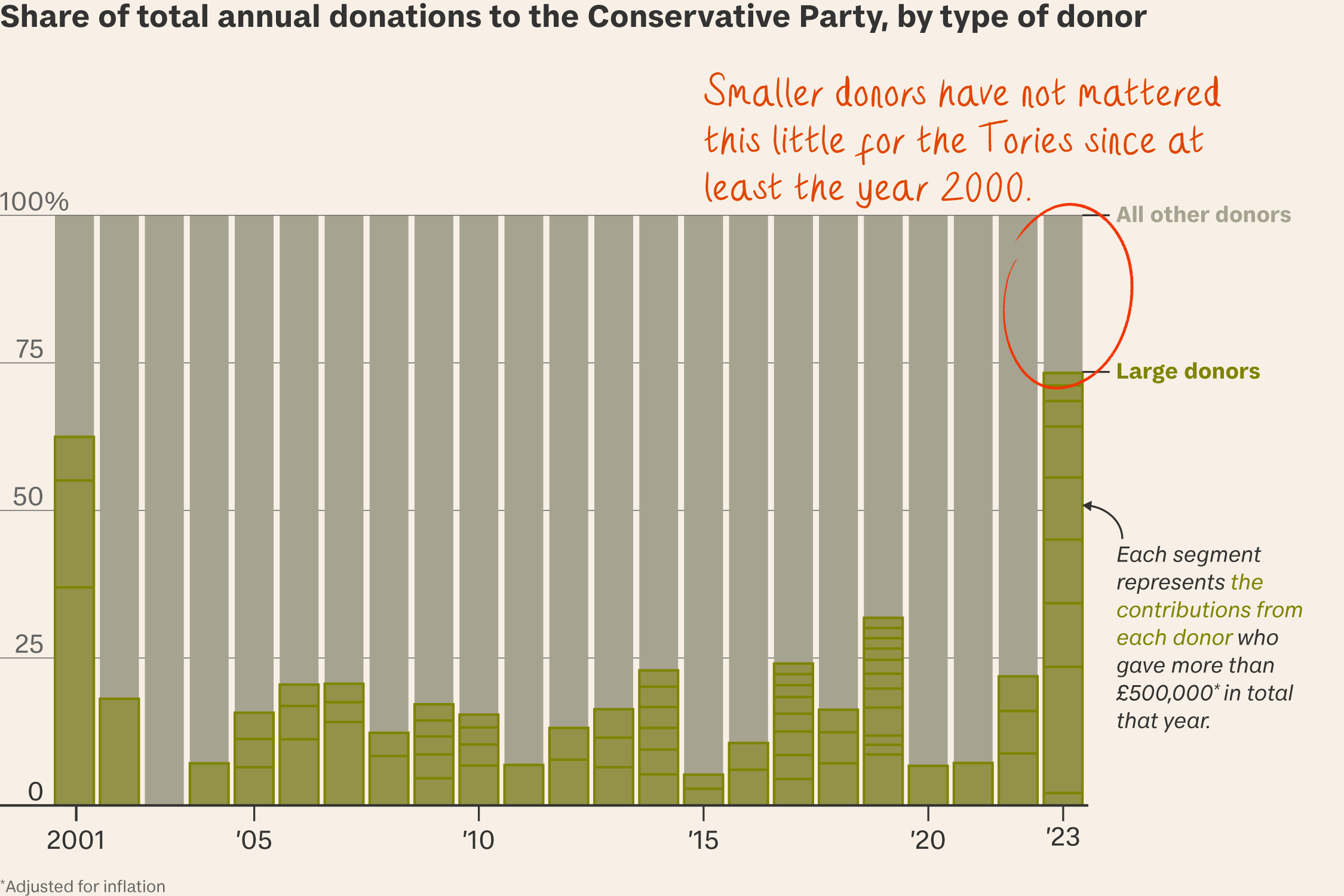

Losing hundreds of MPs is fixable but hard. Losing the ability to raise money makes it harder.

The Conservatives are not just facing electoral oblivion. As they head out of power after years of dwindling public trust in politics, there are signs their once-vaunted fundraising machine is misfiring.

So what? Losing hundreds of MPs is fixable but hard. Losing the ability to raise money makes it harder. Slightly more than half-way through the campaign, the party that for nearly two centuries has considered itself Britain’s natural party of power is

- heavily reliant on a handful of mega-donors;

- raising funds half as fast as Labour; and

- raising funds a tenth as fast as at the equivalent point in its last national campaign, under Boris Johnson.

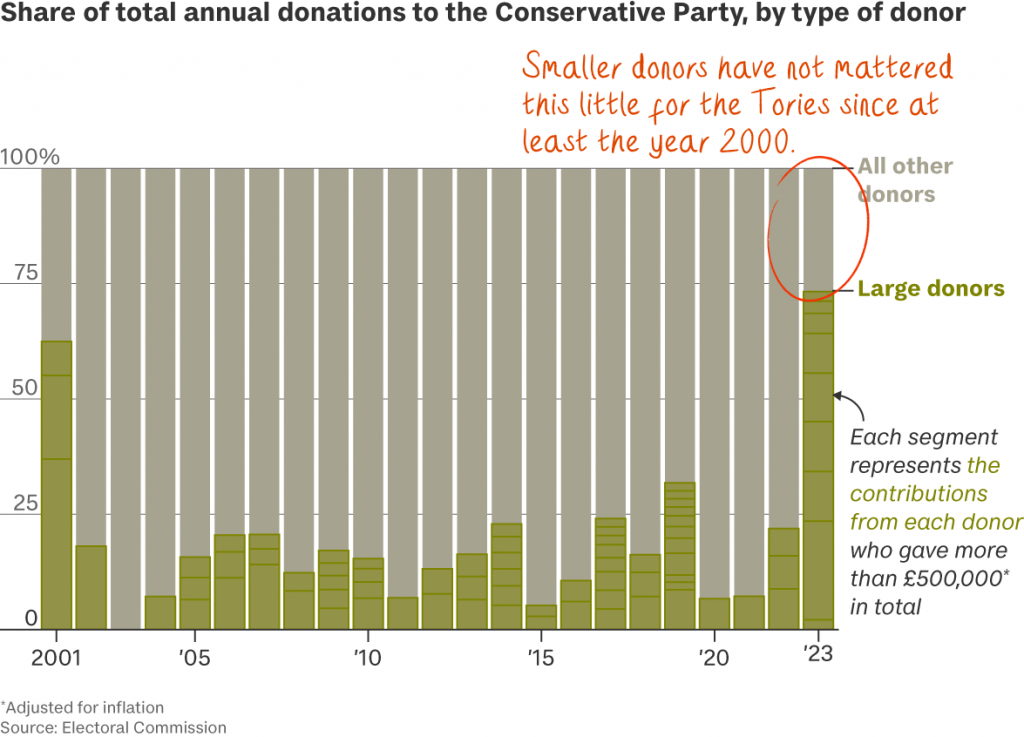

The few. By the end of the Conservatives’ last period in opposition, their top 10 donors accounted for nearly three-quarters of their donations. Those figures flipped to around a fifth under David Cameron and his fundraiser-in-chief, Andrew Feldman.

By 2023, the last full year for which data is available, the party’s top 10 donors were once again giving three quarters of the total.

Political fundraising experts say this is bad practice for two reasons:

- It leads to dependence on big donors continuing to back the party (and many won’t).

- It can mean tapping up donors for loans, as the Tories were forced to do the last time they were in opposition.

One individual has had a particularly distorting effect on the total: Frank Hester.

The self-made Northern businessman has broken records with his £15 million in contributions to the Conservatives. His last declared donation, £5 million given in January this year, amounted to 57 per cent of all donations to the Conservatives in that quarter.

Hester’s arrival on the Tory fundraising scene is part strategy, part accident.

The strategy. The one flaw in Feldman’s broad-based strategy was its London focus. As a result, a new strategy evolved in which the party, led by Northern Treasurer Stuart Marks, was dispatched to look for untapped “diamonds”.

The accident. Hester emerged as the Tories’ donor pool was shrinking after years of intra-party turmoil, leadership changes and the odd referendum. Before last year, he had never given to a political party. He’s told journalists he either voted Green or spoiled his ballot. Then, something changed. The timeline of his donations to the Conservatives is worth considering:

- February 2023: £11,300

- March 2023: £145,000

- May 2023: £5 million

- November 2023: £5 million

- December 2023: £16,000 (use of helicopter)

- January 2024: £5 million

Hester’s largesse grew as the Tories’ poll ratings slumped. He explained his thinking to the Telegraph: “I wouldn’t be giving [Rishi Sunak] any money if he was 20 points ahead in the polls. What’s the point?”

Right mess. Not everyone has followed his logic. Many donors have fled. Hester himself, whose privately held firm has reportedly thrived on public sector data contracts, did not appear in the list of donors who contributed in the first week of the campaign, which may be why Labour out-raised the Tories nearly two-to-one.

Left field. Meanwhile Labour, historically reliant on unions, has attracted its own mega-donors including the Autoglass millionaire Gary Lubner and the Dale Vince-owned green energy group Ecotricity.

Cap fits. Last November the Conservatives raised the election campaign spending cap by 80 per cent to £34 million. British politics is now in the process of finding a new form, and it will be defined by those who can best afford it.