Jacob Zuma, the disgraced former president of South Africa, has turned on his former comrades in the African National Congress (ANC) to lead his own political party in elections at the end of this month.

So what? At a stroke, the divisive 82-year-old whose political career seemed finished has become a central figure in South Africa’s most important elections in 30 years.

- Africa’s most industrialised economy goes to the polls on 29 May.

- The ANC, party of Nelson Mandela and Africa’s oldest liberation movement, has had a three-decade hegemony.

- But it now faces widespread disillusionment – the ANC’s tally is predicted to dip for the first time below the 50 per cent vote share needed to hold absolute power.

A new and uncertain era of coalition government beckons.

The escape artist. Zuma has had so many scrapes that his nickname is the escape artist. Before he became president, he had been acquitted for rape and charged with corruption over a government arms deal.

Yet for South Africans, his real sins were during his 2009 to 2018 administration.

- He was accused of presiding over corruption so grasping and damaging, its name entered South Africa’s lexicon: state capture.

- His friends and allies took control of ministries and state enterprises so they could wholesale loot budgets and assets. The ANC covered for him, then eventually booted him out.

- He was jailed for not testifying at a national inquiry, but served only three months due to ill health.

Zuma denies any wrongdoing and feels betrayed by his former party. He’s even stolen the name of his new one – calling it uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), after the ANC’s old armed wing.

A game of two halves. The first half of the ANC’s 30-year tenure saw record-breaking economic growth and increased access to free housing, clean water and electricity.

The second half has been more than disappointing. The global financial crisis slowed growth, then came state capture and covid. Progress has slowed, or reversed.

By the numbers

£21 billion – was pilfered during state capture

32 per cent – overall unemployment (for Black Africans it is 36 per cent; for Whites it is nine per cent)

60 per cent – youth unemployment

1 – South Africa is the most economically unequal country in the world, according to the World Bank

12 – electricity rationing saw up to 12 hours of rolling blackouts each day for much of 2022 and 2023

The ANC is now presiding over crumbling public services; its municipalities are often debt-ridden and failing. The all-powerful party structure prevents accountability and does not seem to have raised new leaders to compare with Mandela’s generation.

Mandela’s legacy isn’t safe. Disenfranchised young Blacks say they have not benefited from the end of apartheid and blame Mandela for not gaining enough concessions from Whites to make them better off. They are turning to more radical political parties.

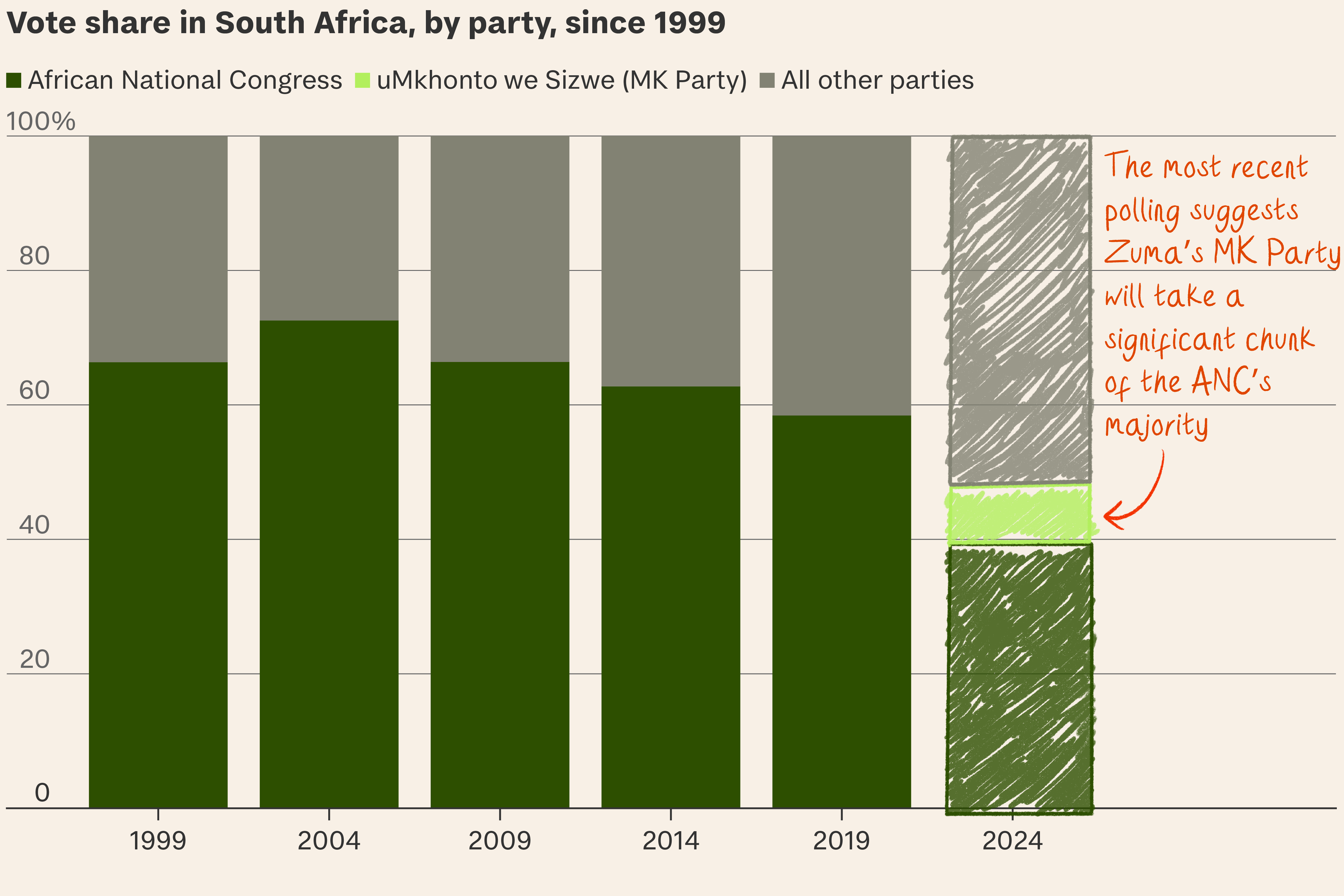

Poll dancing. South Africans’ patience with the ANC is running out. Its vote share was 70 per cent in 2004; 66 per cent in 2009; 62 per cent in 2014 and 58 per cent in 2019. There is a lack of independent polling, but surveys suggest it will be lower still this time, at around 40 per cent.

The emergence of Zuma’s MK has weakened the hard-left Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), but also seems calculated to hurt the ANC – particularly in the key KwaZulu-Natal battleground, which is Zuma’s homeland (and where his followers remain devoted).

What’s more. After 29 May, the ANC will still be by far the biggest party and in pole position to form a coalition. What that looks like depends on how many votes they need: a little below 50 per cent and they can get over the line with small parties; any further means a bigger partner and bigger concessions. Zuma could yet play kingmaker.