Today’s local elections in England are a fresh verdict on leaving the EU.

Starting at midnight yesterday, the UK introduced border checks on EU goods which some importers say could add 60 per cent to prices for British consumers.

So what? Millions of those consumers vote today in local elections. Many of their frustrations can be traced to Brexit. Some have been amplified by Covid, austerity and war, but Brexit has been the defining gamble of the Conservatives’ 13 years in power and it has not paid off.

Britain is an estimated £140 billion a year poorer than it would have been in the EU. Trade in goods is down 15 per cent. GDP growth lags the average for the EU, the G7 and the OECD. Investment stagnated for seven years after the referendum. Immigration is at record levels.

Eight years in, three more things are clear:

- The market crash and exodus of talent that some forecast as an immediate result of voting to leave the EU didn’t happen.

- That was because the vote was not the same thing as Brexit. Withdrawing became a multi-year ordeal in which this week’s new border checks (at the fifth attempt) are a mere chapter.

- Now that Brexit is real, it’s clear the consequences will be deeper, longer-lasting and more widely felt than even the pessimists expected.

Semantics. Brexit’s role in its own debate has been obscured by magical thinking on the right, by timidity at a public broadcaster watching its own back and by self-censorship in a Labour Party determined to win back power. None of them wants to talk about it. But voters deserve an honest attempt at Brexit battle damage assessment, and step one is to call it by its name.

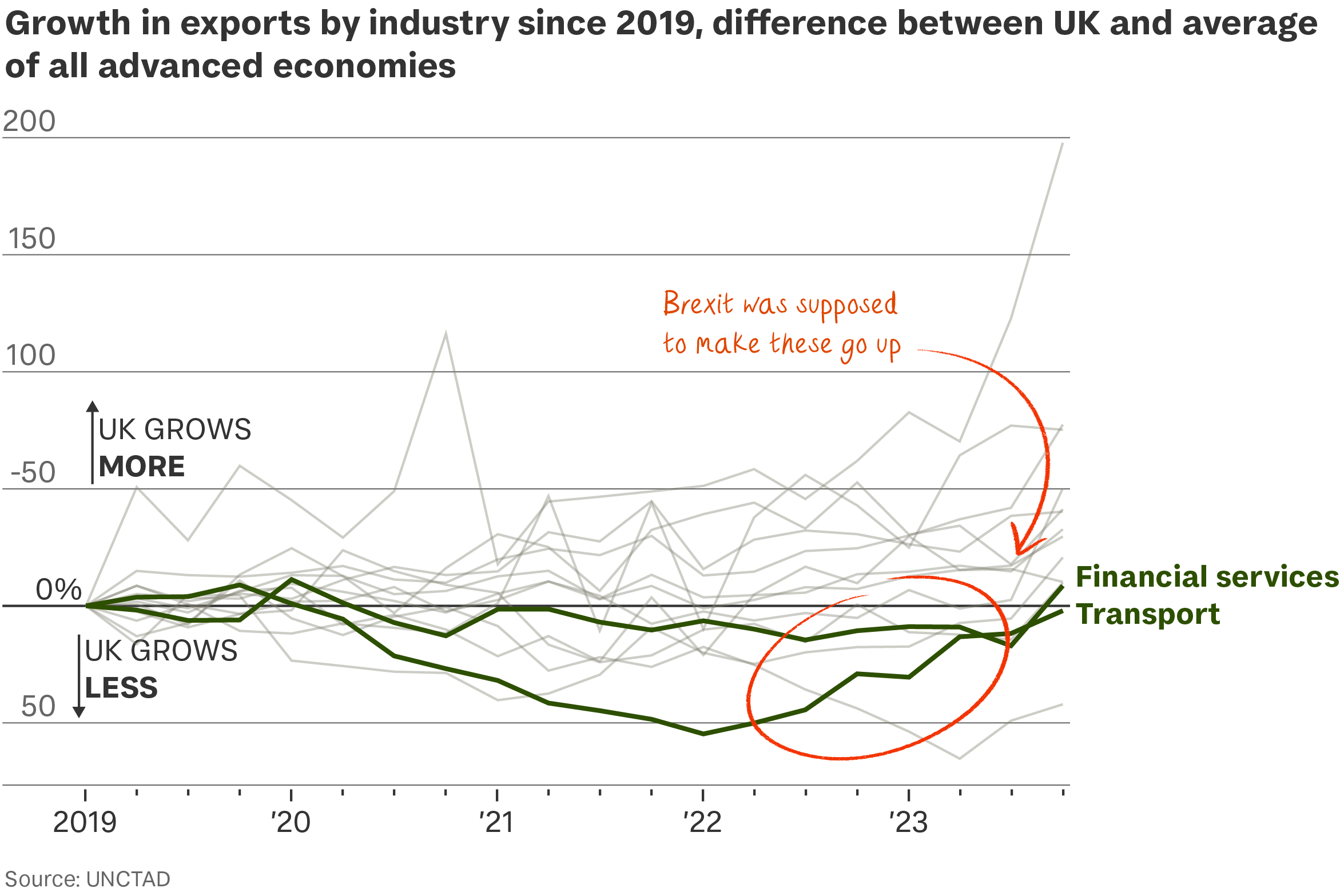

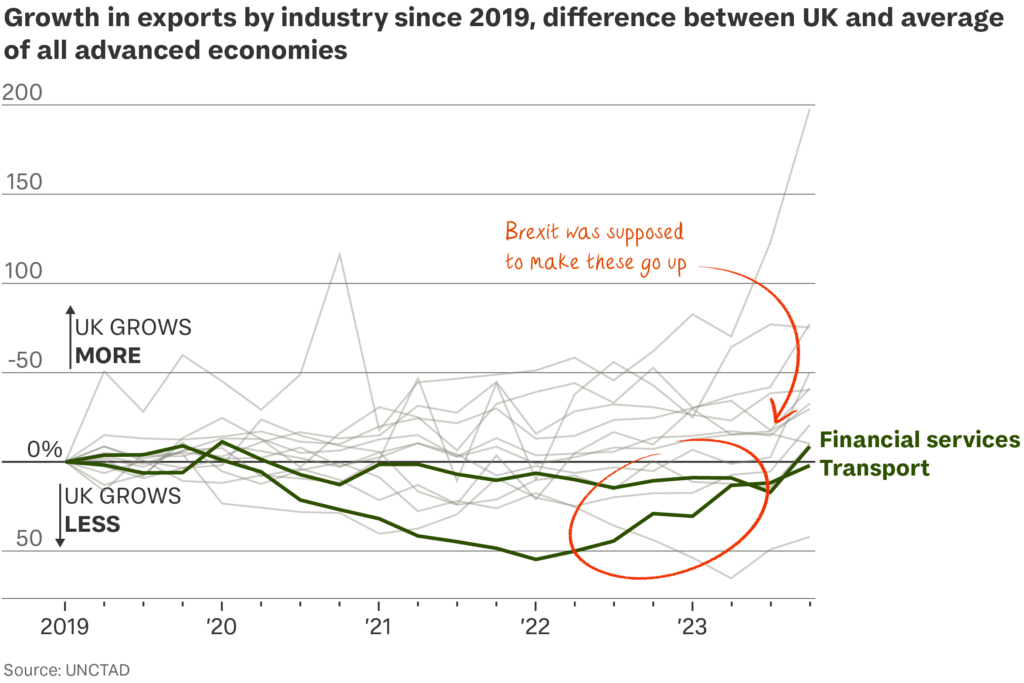

People. The City survived. As few as a tenth as many financial services workers have left for Europe and New York as in the worst forecasts. Last month Goldman Sachs moved its top banker for European financial firms to Paris, leaving only a skeleton staff in London, but the sector accounted for 8 per cent of UK GDP before 2016 and it still does.

The broader picture is bleaker. By ending free movement Brexit worsened labour shortages, fuelled inflation and cost 2 million jobs relative to an in-EU counterfactual, according to a study by Cambridge Econometrics. Immigration by EU workers has been largely replaced by less economically-active non-EU migrants.

Trade. There is a bright spot in the data: last year UK services exports grew 7 per cent to a record £470 billion, boosted by

- low EU barriers to professional services in which Britain excels (including legal, consulting, audit and pensions);

- the weak pound, which devalued by 20 per cent after the referendum, making UK exports cheaper; and

- low wages compared with the US, encouraging American firms to outsource work to the UK.

Otherwise, the post-Brexit trade growth that was supposed to sustain Global Britain is invisible.

- Goods exports to the EU are 23 per cent lower than if they’d grown in line with intra-EU exports, says John Springford of the Centre for European Reform.

- Services exports are 11 per cent lower by the same measure, and financial services exports to the EU fell nearly 30 per cent in value in the first three years of Brexit compared with the sector average for advanced economies.

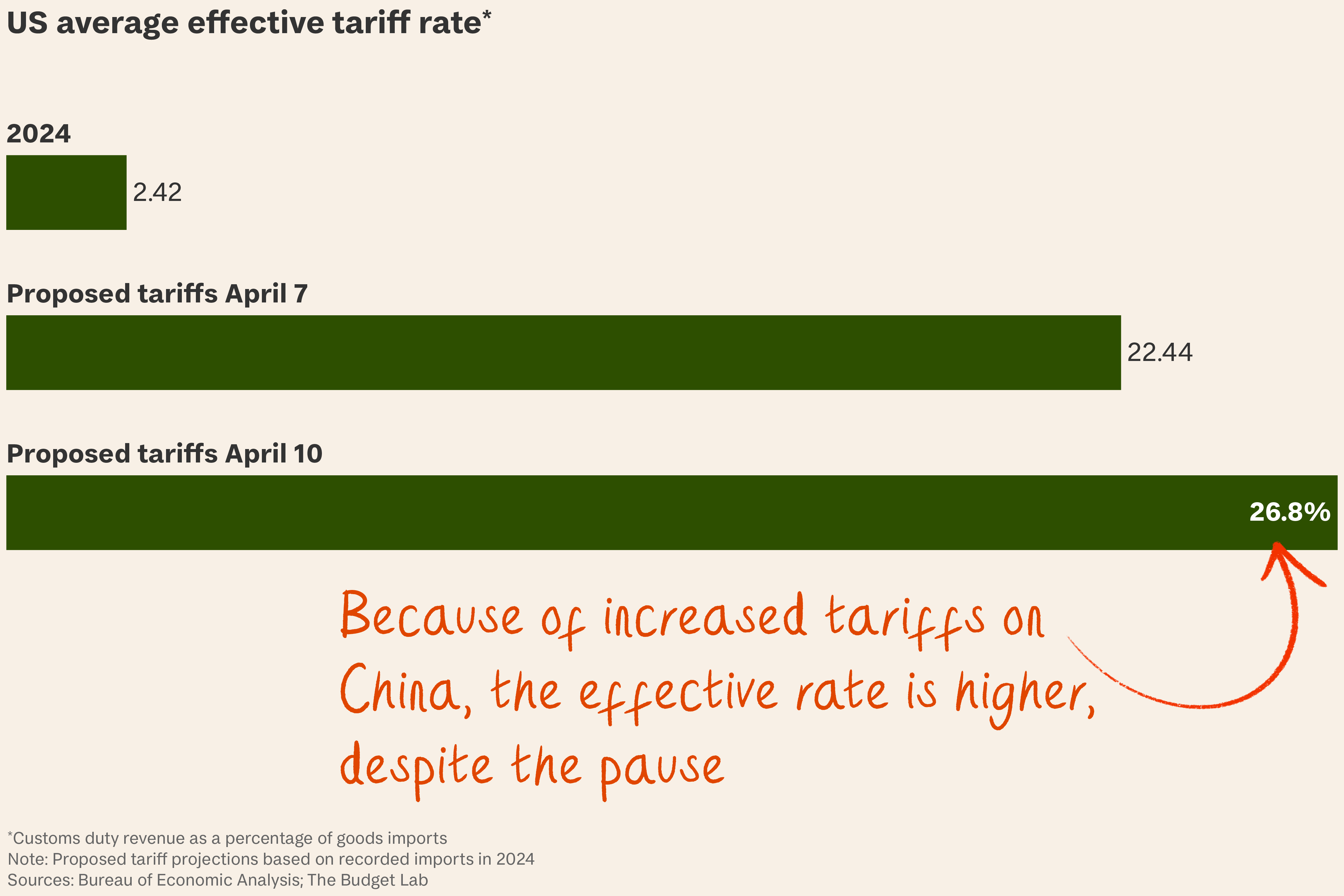

- This week’s border checks add up to £145 per consignment in fees for importers, or up to £3,000 per lorry for those carrying several consignments.

Non-EU trade was supposed to compensate, but hasn’t. It’s stuck at pre-referendum levels. Trade in general was supposed to be frictionless. It isn’t. Free trade agreements with the US and India were promised but have not materialised. An FTA with Australia should boost UK GDP by 0.08 per cent.

Investment. Essential for productivity growth, public and business investment flatlined after the Brexit vote, collapsed with Covid and has failed to keep pace with the rest of Europe since. Cambridge Econometrics says on present evidence it will be 32 per cent lower by 2035 than if the UK had stayed in the EU.

Listings. The value of funds raised by new companies on the London Stock Exchange last year collapsed by nearly 97 per cent compared with the year before (more on this in tomorrow’s Boardroom Sensemaker).

What might have been. Measuring reality against counterfactuals feels unfair to Brexiters but is the only way to gauge the real cost of their project. Comparing the present only with the past ignores hundreds of billions of pounds in growth, jobs and opportunities foregone, not to mention the benefits of free movement to UK citizens and of UK membership to an EU in need of the kind of reform it would have promoted.

What’s more… Most voters see this now. 56 per cent think Brexit was wrong, to 33 per cent who still think it was right – a 36 per cent slide in voter share in eight pointlessly hard years.