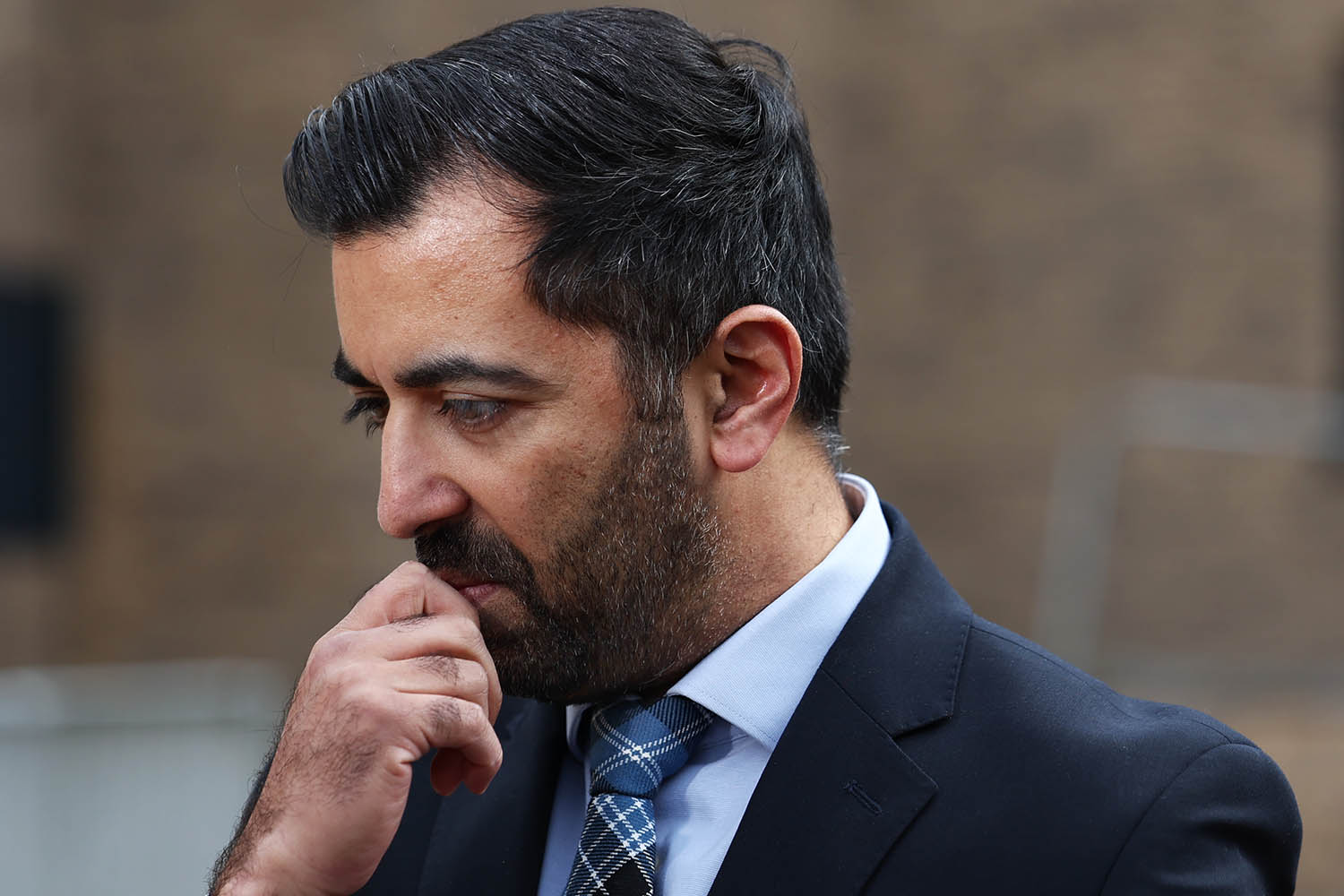

Scotland’s First Minister Humza Yousaf has resigned after just over a year, throwing the country and its minority SNP government into turmoil while pushing big questions about independence further into the future.

With less than a fortnight to go until the 25th anniversary of devolution, the focus is on whether that Blair-era settlement, which established a new Scottish parliament at Holyrood, is being shown up as a failure.

Yousaf, heralded by Time Magazine only a few months ago as the “New Face of Scotland”, fell on his sword rather than face a no confidence vote in which his fate was in the hands of his former leadership rival Ash Regan.

Regan now represents Alba – the party set up by Alex Salmond, the former first minister whose bitter falling out with the SNP and his successor Nicola Sturgeon continues to be acutely felt in Holyrood.

A day is a long time in politics. Inadvertently insightful as ever, Yousaf’s swansong speech included a fantasy that everyone in Scotland be “First Minister for just one day” – drawing attention to his brief time in power. John Swinney, the veteran minister who has previously opted out of running for leader, now looks likely to take on the role as a caretaker.

Yousaf also conceded that he “clearly underestimated the level of hurt and upset I caused Green colleagues”. It was Yousaf’s decision to scrap the Scottish government’s climate goals and torpedo the SNP’s coalition with the Greens that brought about his demise, reinforcing the view held by those who branded him ‘Hapless Humza’ that he was not up to the job.

This is the man who after the arrest of former party treasurer Colin Beattie as part of an investigation into the SNP’s finances, memorably told journalists: “I’m surprised when one of my colleagues is arrested”.

Faintheart. Yousaf left claiming that Scottish independence was “frustratingly close”, and that whoever succeeds him would “lead us over the finish line”. But support for Scotland’s exit from the United Kingdom has actually fallen since peaking at 53 per cent in 2020, when Nicola Sturgeon was winning praise for her deft Covid communications in contrast to the chaos in Westminster. Support for independence is now around 47 per cent – not far above the 44.7 per cent achieved by the pro-independence campaign in the 2014 referendum. In this self-inflicted turmoil, it may fall further. Even if it doesn’t, Yousaf’s chaotic exit is unlikely to win over more converts.

The high(land) road to Downing Street. SNP sources play down the extent to which Scotland will matter in the coming general election, but for Labour strategists the road to Number 10 leads north of the border. After support for their party collapsed under Ed Miliband, leaving just one Scottish Labour MP (rising to two after a recent by-election in Rutherglen), there is a low bar to cross, but Yousaf’s ineptitude will be helpful, particularly if Rishi Sunak starts to claw back support from disgruntled Tory voters.

Devolution evolves. Perhaps the most significant question posed by the SNP implosion is what it means for devolution. In many devolved matters, Scotland is now behind the other nations of the union. Education is in decline (equivalent to 16 months behind for maths, eight for reading and 18 for science), drug deaths are the highest in Europe, and health outcomes are relatively poor (life expectancy for men is 76.5 compared with the UK-wide figure of 78.8).

But views of devolution tend to depend on metrics. On the basis that it ceded centralised power in order to maintain the union, the last 18 months of Scottish politics should perhaps be chalked up as a win.