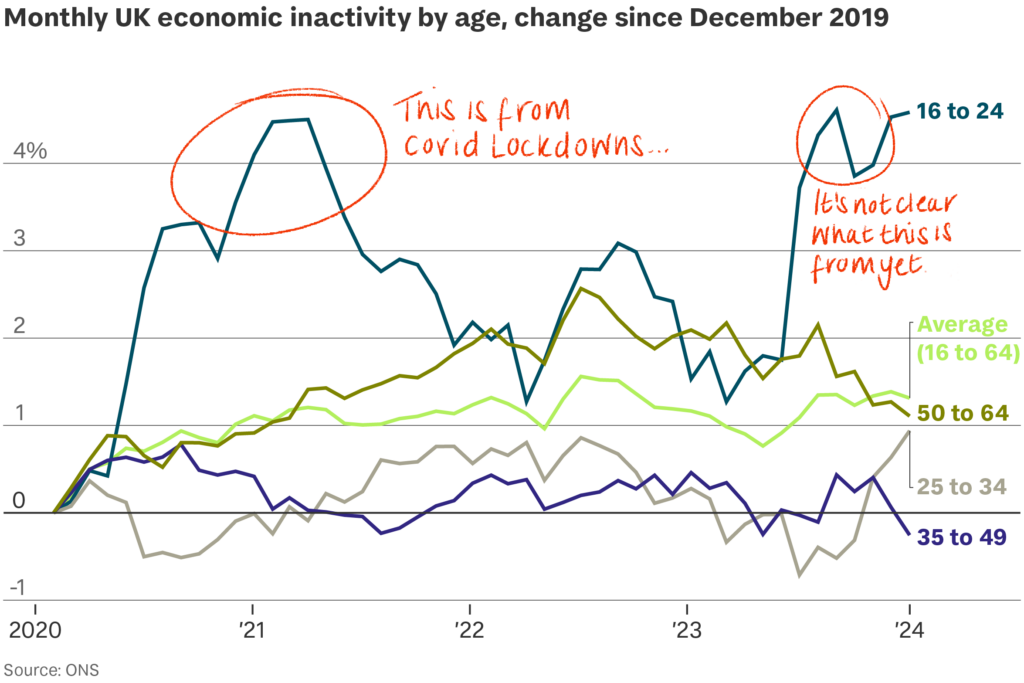

The number of working-age adults in the UK who are unemployed or not actively seeking work has risen above a fifth of the population, the ONS said this week. A surge in economic inactivity among 16 to 34-year olds is the main driver.

So what? The causes aren’t cut and dried but the consequences for business and the economy could be dire.

- A tight labour market is one of the biggest obstacles to cutting interest rates and taming inflation.

- Young workers are vital to certain sectors and a force that spurs innovation.

- If they can’t be hired domestically, the assumption is they’ll come from abroad: uncomfortable territory for a government that wants to bring down net migration.

While the number of people in work has gone up overall in the past year, this isn’t true for the 16-24 age group. Out of 9 million people classed as economically inactive, nearly a third are under 25. This is due partly to

- Students – 2.6 million people who say their studies are the reason they’re not seeking a job – a record high; and

- Sickness – since the pandemic the largest relative increase in inactivity due to long-term sickness has been in the 16 to 34 age group. Mental health was the biggest driver for sickness in this cohort, rising by roughly a quarter. Two thirds of all incapacity benefit claims are for mental health, recent data reveals.

“Hospitality businesses have been forced to open for only a few days a week or not open at lunchtime because they haven’t been able to find the staff,” says Danni Hewson, head of financial analysis at AJ Bell, an investment company. “For employers wanting to recruit and keep hold of staff in a really tight jobs market, it means that they’ve had to resort to paying higher wages.”

Andrew Bailey, governor of the BofE, signalled this week that he’s now less concerned about a wage spiral but Hewson says wage growth is still “uncomfortably high”. As long as skills shortages persist, it will be hard to predict where wages are headed.

Hunt’s secret weapon. The chancellor claims last week’s budget will get Britain working again. The IFS estimates his £7 billion-a-year workforce plan – including tax breaks on pensions and expanded free childcare – will bring 110,000 back into employment. That works out at nearly £70,000 per job.

Paul Johnson, director of the IFS, said that while Hunt “might have some success” it would be modest given the large number of people lost from the workforce in the past two years. The far bigger (and cheaper) boost to employment will come, almost inevitably, from immigration.

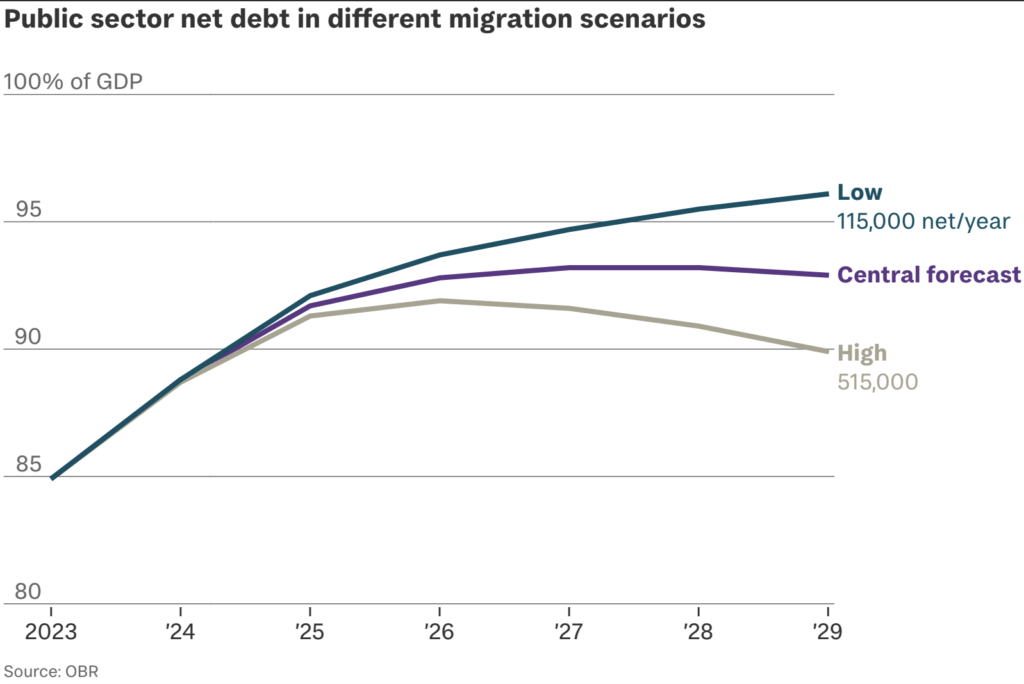

Baked into the Office for Budget Responsibilty’s five-year forecast are assumptions that by the end of 2029 an extra 350,000 people will be living in Britain who will

- contribute an additional £6.2 billion in tax revenue; and

- pay £0.3 billion in fees and charges to enter the country.

Even if the government responded by keeping departmental spending per person unchanged, the OBR calculates that additional migration (up to 515,000 a year) will mean the difference between debt rising or falling as a share of GDP.

Professor Jonathan Portes, Senior Fellow at UK in a Changing Europe, says Hunt is essentially “using higher migration as a way to cut public spending by stealth, and recycling the proceeds into tax cuts”.

Tough choices. With Britain stuck in a quagmire of inactivity, a hike in the minimum salary threshold for skilled workers – due to come into force in April – threatens to make the situation worse for employers. Many sectors – notably care, manufacturing and farming – are lobbying for exceptions or reductions on the incoming Immigration Salary List.

“High immigration costs are an issue for small employers wanting to use the immigration system, but many have responded to recruitment challenges by increasing wages or outsourcing work. We’re calling for immigration fees for SMEs to be capped at £1,000,” says Tina McKenzie, Policy Chair at the Federation of Small Businesses.

Despite the economics, there are still few businesses willing to put their heads above the parapet on immigration. A far less politically toxic option is to find ways to get Britain’s young people into work. That could take the form of a greater focus on

- apprenticeships

- mental health provision

- improving transport options and

- matching skills to jobs.

Since the pandemic, economic inactivity has been rising faster in the UK than any other G7 country. Any future government needs to make slowing it a priority – or accept that it will be foreign workers fuelling the economy.