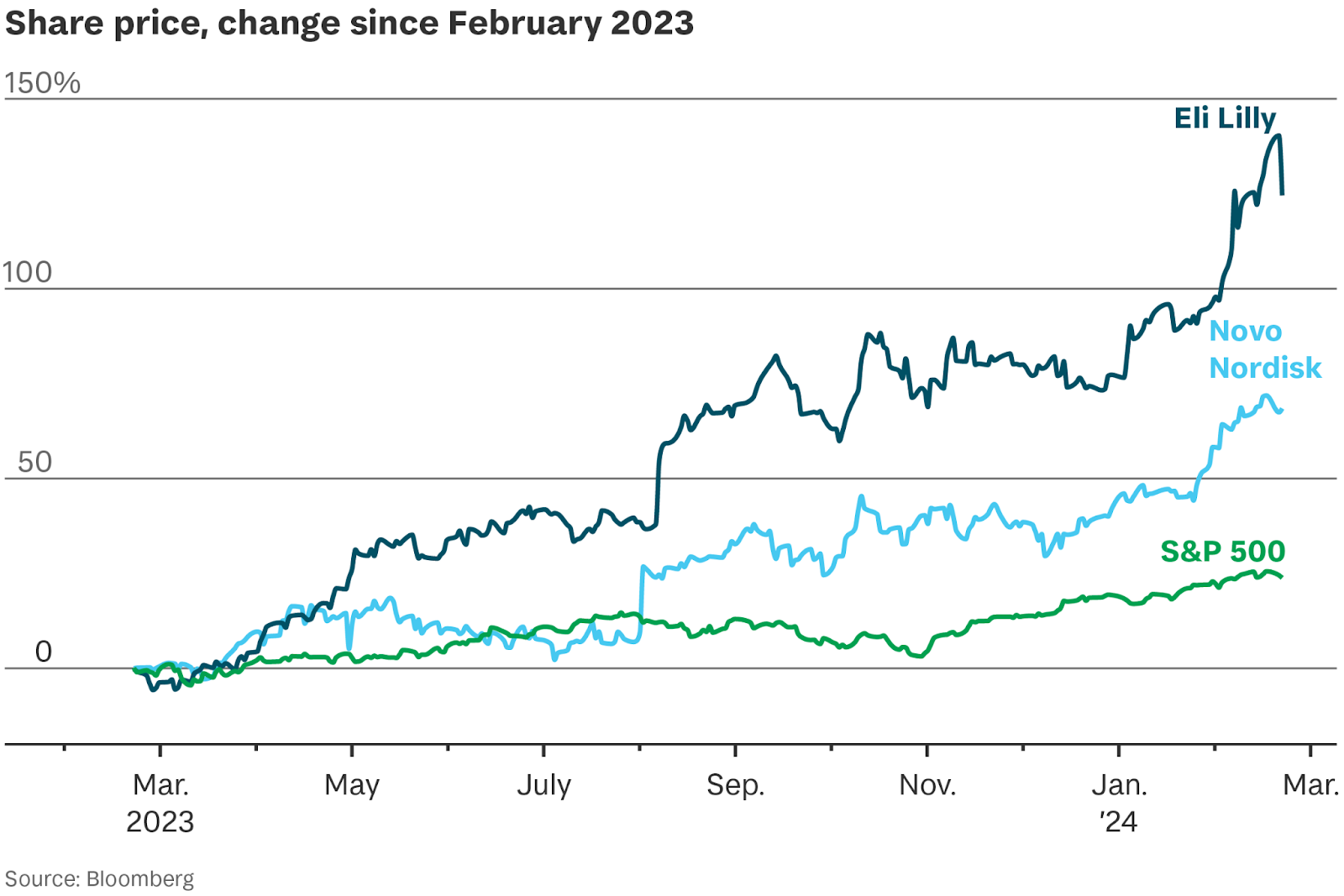

Eli Lilly, maker of the UK-approved weight-loss drug Mounjaro, surpassed Tesla’s market cap last month. Novo Nordisk, maker of rival drug Ozempic, became the most valuable company in Europe last year. Both are fighting it out for the lion’s share of a market forecast to reach $100 billion by 2030.

So what? For all the talk of Magnificent 7 tech stocks, the mighty pharma duo have an oversized place in the markets. Lilly has forecast over $40 billion of revenue in 2024 and is trading at 55 times its earnings (compared with 41 for Amazon). Novo isn’t far behind with a market cap of $555 billion, making it the 14th most valuable company in the world. In addition both drugmakers

- list a nonprofit foundation as their largest shareholder

- stand to benefit handsomely from a global obesity epidemic and

- may soon reap the rewards of research that suggests their products combat an array of ailments, from atrial fibrillation to alcoholism.

They have the first toeholds in a booming market – but their unique position comes with very specific responsibilities to

Consumers. Lilly and Novo’s products are obviously at risk from off-label use by people who just want to get skinny. This means firms have to be extra diligent about how they’re marketed. Novo has already been stung at least once: last year it was banned by a UK industry body for sponsoring courses for health professionals on weight management on LinkedIn, without making clear the company’s involvement.

Weight-loss drugs are also making inroads with the world’s largest obese population – in China. Treatment with Ozempic is officially reserved for treating type-2 diabetes, but it retails online in “grey markets” for around $139 per monthly dosage. Customers using it for weight loss can simply declare they have diabetes without proof.

“There’s a temptation to get in control of the sources of demand. But once you’re in that situation you’re more of a lifestyle/healthcare company than a pharmaceutical company,” says Martin Jes Iverson, vice dean of the Copenhagen Business School.

Regulators. Both companies have had drugs approved by the FDA, which says their products address “an unmet medical need”. Cue debate about what health systems, insurers and even employers should offer in terms of coverage. A monthly dose of Wegovy, Novo’s product that specifically targets weight loss, currently costs about £180 in the UK. Despite their best efforts (Lilly and Novo spent a combined $13 million lobbying Congress last year) several US states recently introduced limits for what’s covered under Medicaid and state employee health benefits. NICE, the UK health authority, says it will pay for patients with higher BMI who already have at least one weight condition, albeit only for two years, despite evidence that weight is regained after coming off the drug.

Shareholders. Novo isn’t trying to cater to the mass market (not yet at least). Instead it’s focused on getting authorities and the public to accept the argument that severe obesity is a disease that needs to be treated with medication, rather than a lifestyle problem. As well as substantial PR muscle, that is going to require embedding a culture within the company.

That Novo’s largest shareholder is a purpose-driven nonprofit may help. The Novo Nordisk Foundation holds most of Novo’s voting rights and 28 per cent of its shares. This gives protection from acquisition but also encourages long-term thinking.

“It’s a very smart structure because you have this incentive to be sharp because you’re listed and liable to the market,” Iversen says. “At the same time you don’t always have to optimise shareholder value – you can think ahead.” Hybrid structures have been pioneered at other Danish companies including Maersk and Carlsberg. They’ve made it work (in a way that OpenAI conspicuously hasn’t).

As for Lilly, its biggest (non-controlling) shareholder is the Lilly Endowment, a foundation that mainly donates within the state of Indiana – although it may soon broaden its horizons. Lilly’s stock price surge makes the endowment America’s second largest philanthropy behind the Gates Foundation.

Just desserts? There’s bound to be turbulence that could upset Lilly and Novo’s head start in the market. The age of the superstock, both in tech (AI) and pharma (obesity), hasn’t just caught the attention of investors, but antitrust regulators too: Lilly is already calling for scrutiny of an $11 billion deal by Novo to snap up additional manufacturing capacity.

Politicians may also take note of pharma’s windfall – and decide that a portion ought to be spent on over-stretched public healthcare systems and scientific research. Both companies will do what they can to avoid going on a diet.