Mouayed Bashir, 29, died after being restrained by police who didn't understand enough about his mental state. What does it tell us about the UK's mental health crisis?

Last week an inquest found that police in Wales who restrained a man before he had a cardiac arrest didn’t understand enough about his mental state.

So what? The man died. Mouayed Bashir was a victim of inadequate police training and an epidemic of mental illness to which the UK lacks a coherent response.

Cancer will dominate Britain’s national health conversation while King Charles undergoes treatment but in the meantime

- the task of responding to a soaring number of mental health emergency calls is taking up to 40 per cent of police time;

- the quality of response is declining as police increasingly reject the role of first responder in such cases regardless of whether alternatives are in place; and

- the crisis has echoes in the US, where 14 big cities are trying to take mental health emergency response out of police hands.

Mouayed’s story. Bashir, a 29-year-old Black man with pre-existing mental health problems, died in hospital in February 2021. His parents called emergency services to their family home in Newport because he had barricaded himself in his room and they were worried about his safety.

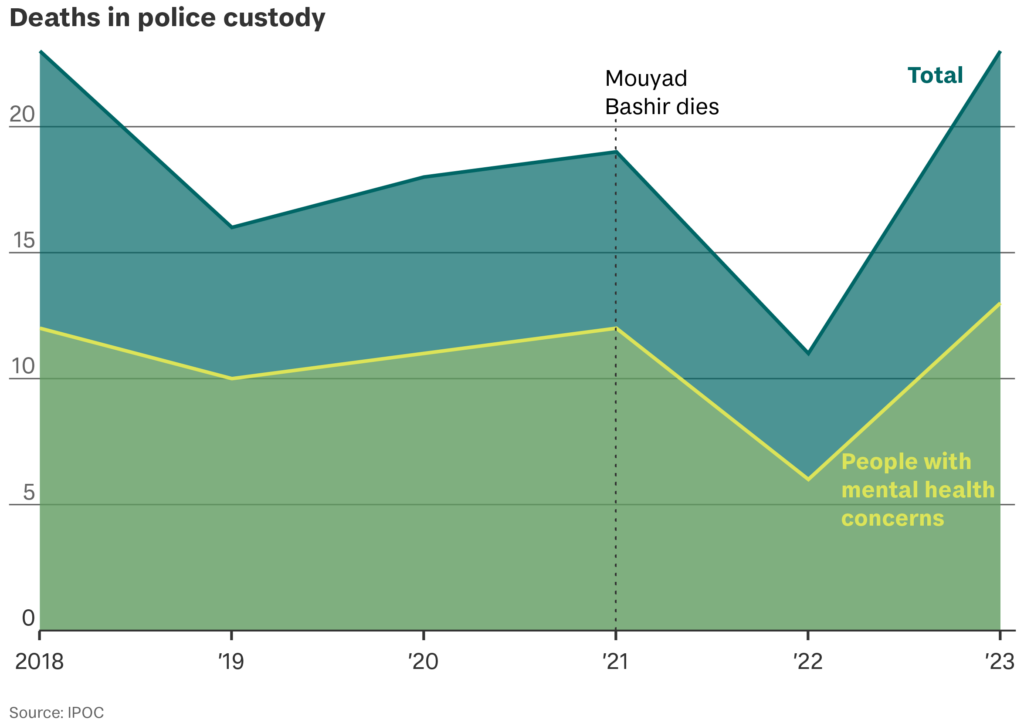

A jury at his inquest concluded police had “insufficient knowledge” of the severe psychological symptoms he was suffering. His death is one of several high profile cases which have drawn attention to the number of people with mental health concerns dying during police contact.

The inquest heard evidence that Bashir was suffering symptoms in line with “acute behavioural disturbance” after taking cocaine. ABD is a medical emergency which can present as extreme distress or agitation. Several officers said that – despite receiving ABD training – they didn’t spot the signs. The coroner accepted that even if ABD had been spotted, it would not have changed the outcome.

The context. Police have become the new frontline for mental health in the UK as the NHS struggles to cope with a steep rise in patient numbers.

- Between 2016 and 2022, NHS mental health referrals increased by 44 per cent. The mental health workforce increased by 22 per cent.

- According to data collected by the BBC, police in North Wales responded to more than five times as many mental health incidents in 2022 as in 2017.

- Police say they’re not qualified to deal with most incidents.

Wrong people, right people. Last year the government announced a nationwide shift to ‘Right Care, Right Person’, a partnership between police and NHS services in which non-essential mental health calls are diverted away from police to health professionals.

RCRP means police will stop attending incidents unless there’s a significant risk to life, which the National Police Chiefs’ Council estimates could save a million police hours a year in England alone.

Too much, too soon? Experts have welcomed the spirit of the strategy, but there’s concern police are withdrawing support before alternatives are in place.

- In Humberside, where the model was pioneered, the force gave health bosses over a year to prepare for the RCRP strategy.

- London’s Met police originally gave health and social care providers just 99 days’ notice, although this was later extended by two months.

Will it work? The UK is “adopting a policy based on little evidence”, says Andy Bell, CEO of the Centre for Mental Health. There are concerns that too much focus has been placed on saving police hours and too little on health outcomes – but “police cannot and should not be first responders to people in mental health crisis,” says Lucy McKay, from INQUEST, whose lawyers represented Bashir’s family. His death is a stark reminder of what’s at stake.

What’s more… Parliament’s Health and Social Care Committee estimates that the RCRP model will need £260 million in extra funding, but the Department of Health and Social Care says there is currently no additional funding specifically allocated for the strategy.