Unfair isle. Four million people in the UK experienced destitution* in 2022. Forty-three per cent of the country’s most disadvantaged children leave primary school without reaching expected standards in reading, writing and maths. People in the lowest income bracket are three times more likely than average to suffer mental illness.

So what? Prime Minister Rishi Sunak won a vote on the UK’s Rwanda-based asylum scheme this week but it was an object lesson in displacement activity. The Rwanda plan is a stag fight between Conservatives that will go nowhere in the real world. Voters have more important things to worry about including

- rising inequality;

- stalling growth; and

- labour shortages and the reality of immigration.

In reverse order:

Unemployment at 3.5 per cent has not been so low since 1973. It has created urgent labour shortages in healthcare, social care, hospitality and construction, not remedied by record net inward migration last year of 745,000. This is the essential context of the small boats immigration saga.

Immigration numbers that matter (for the year ending June 2023 unless otherwise stated) include:

- 3.7 per cent – small boat immigration as a share of total inward migration (44,600 of 1.2 million).

- 4.3 per cent – total illegal immigration as a share of total inward migration (52,500 of 1.2 million).

- 1.2 million – total inward migration, of which 129,000 from EU countries, 968,000 from non-EU countries and 84,000 returning UK citizens.

- 980,000 – projected total inward migration for 2023, of which 7.4 per cent from Ukraine, 5.3 per cent from Hong Kong, 5.1 per cent asylum seekers, 0.51 per cent resettled refugees, 42 per cent study visa holders, 29 per cent work visa holders, and 6.1 per cent family reunion visa holders.

- 420,000 – overseas students entering Britain this year, attributed by the Migration Advisory Committee’s annual report today to “a clear [government] policy in place to increase the number of international students”; financial pressure on universities to attract overseas students; and the attractiveness of post-study work visas offered to graduate students since 2019.

Stalling growth. The UK economy shrank unexpectedly by 0.3 per cent in October after growing by 0.2 per cent in September.

Rising inequality. Inequality in Britain is high and rising. It’s worse than in most of the rest of the rich world and much worse than it needs to be. The lingering trauma of the 2008 crash and the triple shock of Brexit, Covid and a cost-of-living crisis triggered by war and Liz Truss have left the country riven by want.

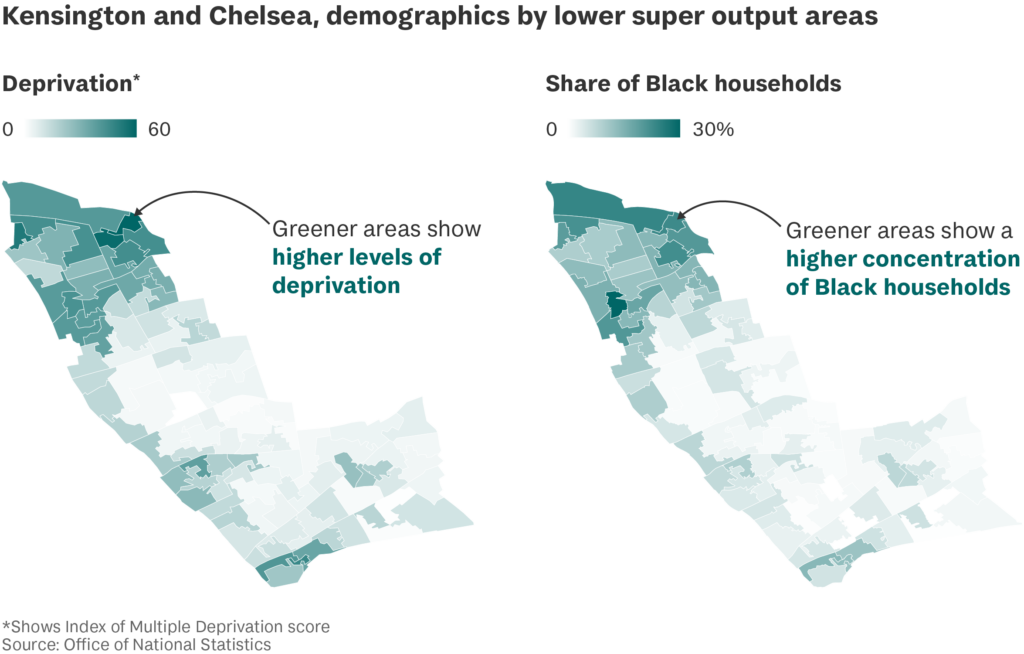

This gulf is

- regional – average earnings in Kensington are four and a half times those in Nottingham;

- generational – the proportion of children with mental health problems has doubled in the past two decades; and

- intra-urban – even prosperous towns and cities host pockets of acute deprivation often borne mainly by ethnic minorities (see graphic).

Don’t take our word for it. Two book-length reports released in the past week by high-profile think tanks, one on the centre-right and one on the centre-left, agree on the diagnosis if not the prescription.

- Two Nations, from the conservative Centre for Social Justice (CSJ), depicts a UK still poleaxed by the pandemic and failing entirely to bring the poorest 20 per cent along with the rest of society despite a decade of purported levelling up by Conservative governments.

- Ending Stagnation, from the (Blairite) Resolution Foundation, calculates that 15 years of zero real wage growth are costing the average UK worker £10,700 a year, and says playing to Britain’s strengths as a service economy is the route out of its productivity trap.

Modest proposals. The data is not obviously cheerful but there’s no need to be overwhelmed by it:

- First, serve. The UK is the world’s second biggest exporter of services. Its strength is in comms, IT, marketing, education and culture as well as finance. Margins tend to be higher in services than manufacturing. That fuelled British prosperity in the 90s and 00s and could again.

- Then help. The poorest need more money. Current plans to move them onto Universal Credit mean most recipients get less, and ministers need to recognise this will only increase destitution.

- Know thyself. Low income households in the UK are £4,300 a year worse off than in France. Even middle income households are 20 per cent poorer than in Germany. Reform has to start with an honest assessment of how bad things are.

Ceul Britannia. The last long decline of an unpopular Conservative government, in the 90s, coincided with a cultural resurgence that some people were unembarrassed to call Cool Britannia. Maybe this time it’ll coincide with a return in some form to common sense, and Europe.