In his new book, Daphne’s son Paul puts her life to page, laying bare the corruption and cruelty that led to her murder

The dogged loner exemplifies the trade of investigative journalism, but the work is labour-intensive for often scanty return, and practitioners vary in quality and repute.

The celebrated muckraker IF Stone is known to have been a Soviet spy. Seymour Hersh, who broke the story of the My Lai massacre in the Vietnam War, now retails conspiracy theories disputing the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons.

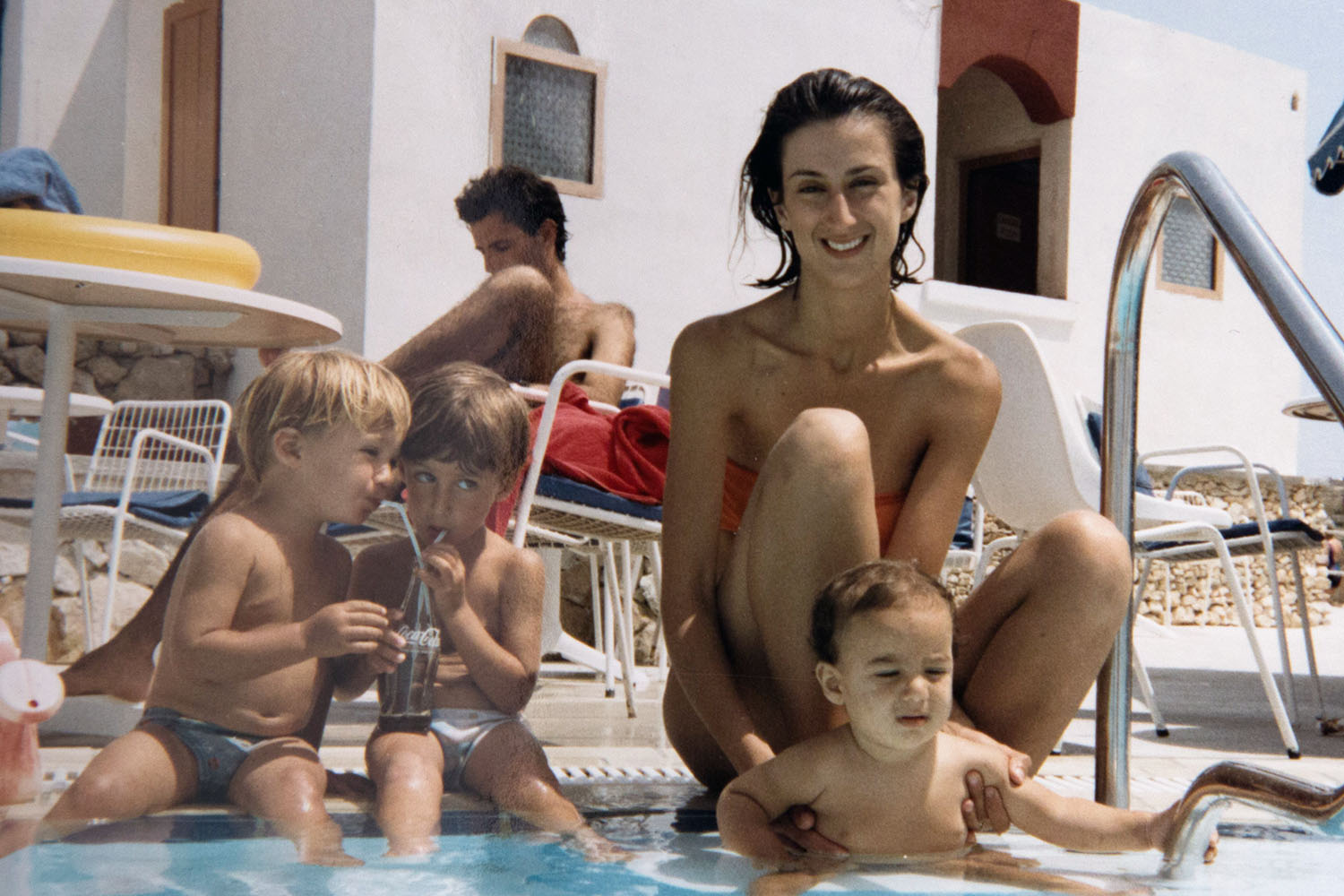

Daphne Caruana Galizia was the real thing: a fearless, independent truth-teller. Her son Paul has written an enthralling account of her life, violent death and legacy.

The book is a testament to journalism at its most vital. It demonstrates how injustice thrives unless there are people brave enough to confront it.

In the patriarchal society of Malta, Daphne Caruana Galizia excelled as a journalist for 30 years. Her blog became the most widely read news source in and about Malta, exposing malfeasance and corruption at the heart of government. “The country was awash with dirty money,” writes her son, and the issue came to dominate her writing.

Amid much else, she published allegations linking prominent politicians, including a mediocrity called Joseph Muscat, then prime minister, to tax havens exposed in the Panama Papers leak.

She accused Muscat’s aides of using shell companies to launder money for kickbacks they’d received for selling Maltese passports to Russian nationals. She made enemies in high places, who responded with libel suits. And in 2017, at the age of 53, she was murdered in a car bombing.

The book’s depiction of the mores of a restrictive society and the determination of a talented woman to break it open is inspiring and often moving.

Of the assassination, Paul Caruana Galizia notes harrowingly that his brother, Matthew, “realised he was surrounded by our mother’s body parts”. Thereon the narrative recounts a heroic search for justice by the author and his brothers, father and aunts.

Three low-level thugs have since pleaded guilty and are serving long jail terms; weightier figures, including a prominent businessman, Yorgen Fenech, are due to stand trial.

Maltese society is culpable too. Paul Caruana Galizia writes excellently, vividly evoking the cupidity of the governing class and with a gift for acute historical précis. He conveys how a small country became in effect a fiefdom and cartel under the baneful influence of the Labour prime minister Dom Mintoff and his successors, such that, ultimately, Daphne “was killed to stop the Maltese people knowing they were being defrauded by their own government”.

The book navigates fluently the complexities of how Malta’s integration into the European economy gave enhanced scope for corruption, as the banking sector became internationalised. It is implicit, but bears stressing, that Malta’s membership of the EU has bound it to observing European standards of justice, which has aided the family’s campaign.

It’s a pity that, with so important a book, Penguin has skimped on proofreading; hence we get both “liquified” and “liquefied” natural gas (the second is correct), “homogenous” for “homogeneous”, typos and transcription errors. A Death in Malta amply merits plaudits, a wide readership, and a clean edition.

Paul Caruana Galizia is a reporter for Tortoise.