- China banned Japanese seafood after Tokyo started releasing treated radioactive water from the Fukushima nuclear plant.

- The Taliban stopped female Afghan students from travelling to the UAE on an education scholarship, according to their sponsor.

- The Brics group of emerging markets invited six new countries to join as members.

In its final minute in the air, the Embraer jet apparently carrying Yevgeny Prigozhin to his death went on a wild roller-coaster ride as the pilot appeared to wrestle with the controls. Then it plummeted to the ground. Before that there was no sign of anything amiss.

So what? What exactly happened to the jet and on whose orders will be the subject of theories for years to come, but evidence that it was deliberately destroyed has stacked up so fast as to be overwhelming.

- Russian aviation officials were able to confirm the crash and Prigozhin’s name on the manifest within minutes.

- Dmitry Utkin, founder of the Wagner Group and a loud critic along with Prigozhin of Russia’s conduct of the war in Ukraine, was also on the plane.

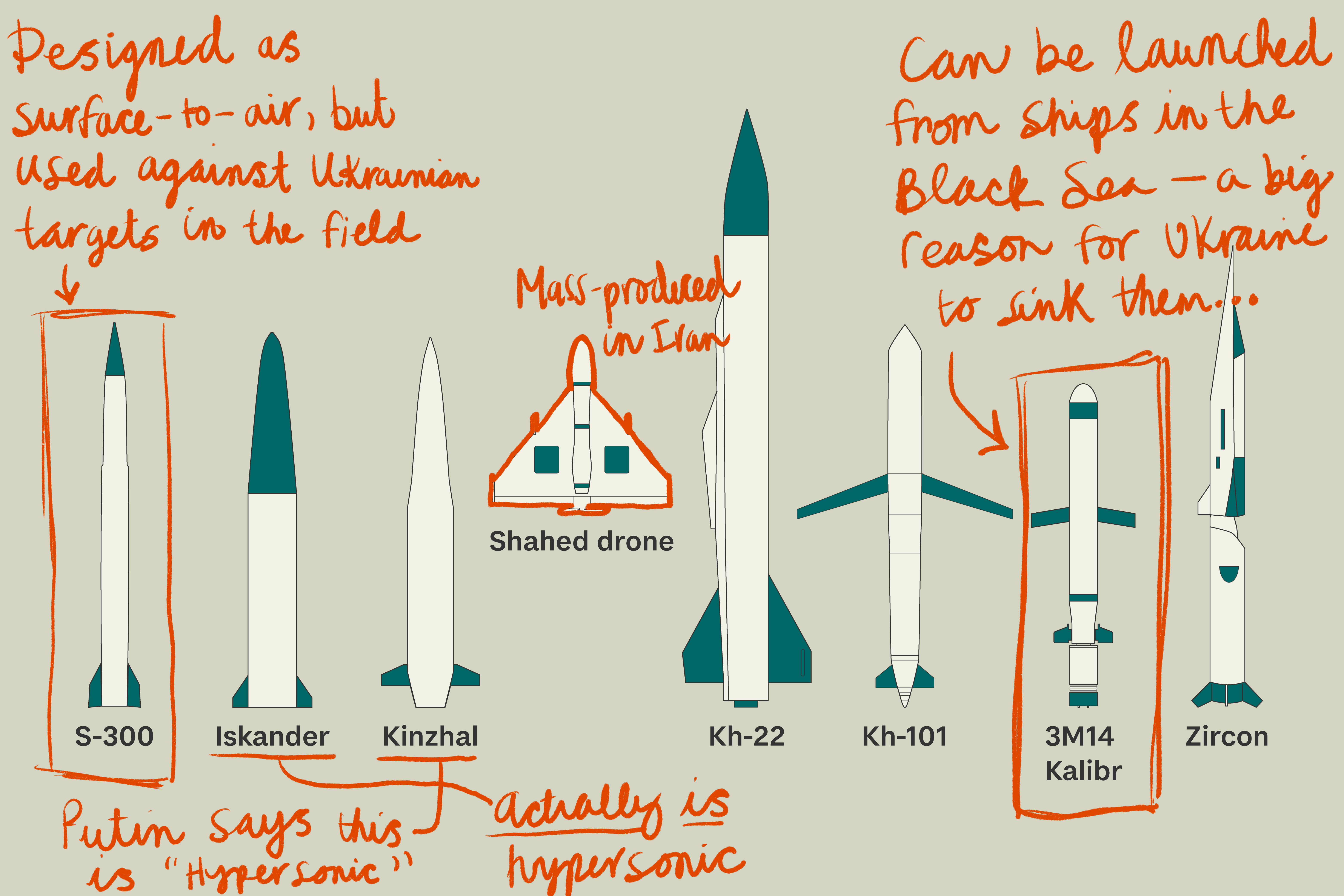

- A pro-Wagner Telegram channel reported two bursts characteristic of surface-to-air missile detonations shortly before the crash.

Prigozhin’s death has not yet been confirmed by the Kremlin and Telegram channels aren’t the most reliable sources, but in key respects his demise – two months to the day after the Wagner Group’s abortive march on Moscow – already fits a pattern familiar from 23 years of doomed if increasingly sporadic challenges to Putin’s authority.

Disloyalty means death. Before Prigozhin there were, among many others, Boris Nemtsov (gunned down on a bridge opposite the Kremlin, 2015), Alexander Litvinkenko (poisoned in London, 2006), Anna Politkovskaya (shot in her Moscow stairwell, 2006) and Artyom Borovik (crashed on take-off from Moscow’s main airport, 2000). The list excludes more than a dozen Russian emigres thought to have been assassinated in London after falling out with Putin, and at least as many senior Russian business figures murdered or “suicided” since the start of the Ukraine war.

Daytime for primetime. Like Nemtsov’s death but more so, Prigozhin’s doomed flight seems to have been orchestrated to send an unmistakable signal to anyone else considering a challenge to the Kremlin. As Tass confirmed the crash, footage of the plane falling in broad daylight was already viral on social media.

Strength through fear. When primetime came, Russian state TV’s appetite for the story was in fact limited: Channel One, an obedient instrument of Kremlin message control, devoted all of 30 seconds to it. Foreign TV crews seeking public reaction on the streets of Moscow found few if any people willing to lament Prigozhin’s passing.

But his life and presumed death are not easily bracketed with those of Putin’s other critics. For nearly two decades he was not just Putin’s “chef” but his most enthusiastic sycophant. The war and Wagner turned that relationship on its head. By the time Wagner troops took Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine this spring, Prigozhin was Russia’s angriest critic of the defence establishment and the only prominent Putin ally to have publicly rejected his rationale for the war.

He is now the only prominent Putin critic to have left behind thousands of aggrieved fighters. They could still pose a threat.

- One pro-Wagner blogger, Roman Saponkov, said Prigozhin’s murder would have “catastrophic consequences” for those who ordered it and who “don’t understand the mood in the army or the morale at all”.

- Another wrote that Prigozhin was the victim of “traitors of Russia”.

- The Grey Zone Telegram channel located the crash site at 10 km from a Russian air force base equipped with surface-to-air missiles and 30 km from one of Putin’s country residences.

Who? If the missile theory proves accurate, the plane will probably have been brought down either by regular armed forces or the FSB from which Putin comes and to which many insist he is still beholden.

What next? “When a dictator is reduced to murdering members of his inner circle and fighting with and replacing his own generals, the situation is very dangerous,” says Garry Kasparov, the chess grandmaster and former opposition leader. “There is no trust among those who remain, and therefore no loyalty.”

That may prove wishful thinking, but it has a chess player’s logic.

Photograph Telegram /Anadolu Agency via Getty Images