An industry once at the centre of Britain’s towns and cities is on life support

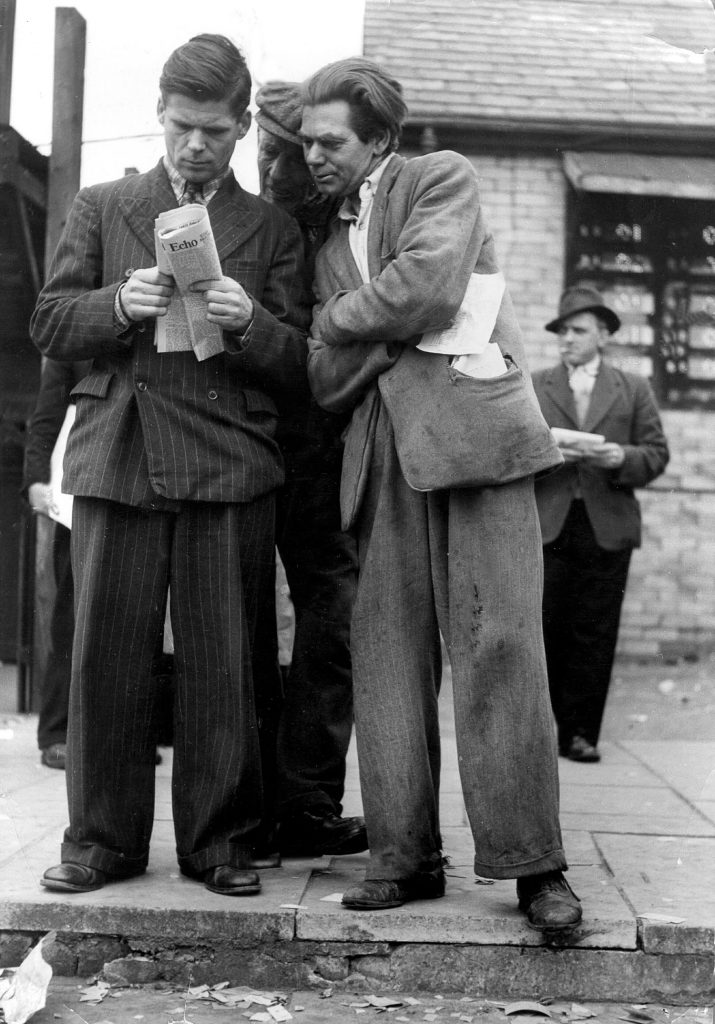

“In scores of towns and cities where once the battle for freedom of news and opinion found its daily reflection in the challenge and counter-challenge of competing morning and evening newspapers with deep roots in local interests and loyalties, the position has so altered that in fifty-six of the sixty-six provincial cities which are capable of sustaining any sort of daily newspaper press those who wish to read a paper concerned with the social and civic problems of their region must content themselves with what is offered to them by one evening paper only.”

That, from former national news journalist and editor Francis Williams, is a fair and familiar reflection, no doubt recognisable to many people, on the recent decline of the local press in the UK.

Except Williams wrote those words for his book Dangerous Estate: The Anatomy of Newspapers, which was published in 1958. He goes on to say, in my hardback copy (12 shillings and sixpence): “Nor in this time of vastly increasing newspaper readership, of expanding education, and of towns and country planning with its stimulation to civic consciousness, have even the provincial weekly papers, for so long the traditional voices of their communities on matters of local concern, fared any better. At least 225 such papers have been forced to cease publication during these thirty-eight years [since the end of the First World War].”

Williams, later Baron Francis-Williams, was well placed to take the temperature of the British press. He had learnt his craft on the Bootle Times, the Liverpool Courier and the Evening Standard before taking the editorship of the Daily Herald until 1940, when he became controller of press censorship and news at the Ministry of Information and, after the war, adviser to Labour prime minister Clement Attlee. Quite what he thought when the Herald ceased publication in 1964 and was relaunched as the Sun is anyone’s guess.

Even 64 years ago the local press was considered to be in decline. Williams may have been shocked by the death of 225 newspapers in almost 40 years; what would he think of the most recent analysis by the UK newspaper trade magazine, Press Gazette, which pointed to 265 local newspaper closures between 2005 and 2020?

And is it really surprising? For anyone under 40, the very act of buying a local newspaper seems archaic, pointless even. Physical newspapers are static, unmoving, fixed; a snapshot of news frozen in amber. A report of something that happened on Monday, heard about on Tuesday, printed on Wednesday. Yesterday’s news, tomorrow. Why would you walk to a shop, hand over money and take home a newspaper to read about something that happened two days or more ago? Especially when you can read it for free, as it happens, on your phone, with an instantaneous cascade of opinions and commentary on social media. On Twitter and Facebook, Monday’s news is reported, picked over, memed, goes viral and is forgotten before the slumbering leviathan of the doughty old printed local newspaper media has even begun to rouse itself.

In 1853 Thomas Wall, a printer, started a newspaper in his home town of Wigan, Lancashire. He named it the Wigan Observer and District Advertiser. It came out every week, a 16-page broadsheet filled with closely typeset columns of council reports, crime stories, advertisements… anything and everything that happened in Wigan.

The Wall family owned and ran the paper until selling it to United Newspapers in 1966. More than a decade earlier the “Obbie”, as it is still known today, had been joined by the Evening Post and Chronicle, the town’s first daily paper. With incursions from newspapers in Manchester and Liverpool, between which Wigan sits roughly equidistant, the town was a hotbed of journalistic competition, stories keenly contested and fought for by a press pack of dogged hacks. Francis Williams might have been sounding the death knell of the local press in 1958, but from today’s vantage point it looks to have been in rude health.

Three years after Dangerous Estate was published, into the offices of the Obbie walked the young Geoffrey Shryhane. He was 15 and the son of a miner in the Wigan pit community of Hindley. He had a fascination with newspapers and had quietly paid for lessons in Pitman shorthand. Seventy words per minute won him the job, ahead of several grammar school candidates.

Thirty years later, I joined my hometown paper, the Wigan Evening Post, formerly the Evening Post and Chronicle. I was 21. I had grown up with the Post and Chron, and the Obbie. Geoffrey Shryhane was a local celebrity. Most towns had someone like him, a reporter and columnist who had worked on the local paper since time immemorial and who had become its public face. The 5ft 3in dynamo could be seen scurrying around town covering everything and everyone. He was a regular at the Wigan Little Theatre and reviewed every show at the big Manchester theatres – the Palace and the Opera House – for decades, becoming as much a fixture as the Coronation Street stars who always frequented opening nights.

Indeed, Shryhane was an even bigger star than they were, in celluloid terms. The 1988 film Testimony, about the life of Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich, was partly shot in Wigan, which doubled up nicely for the Soviet-era Motherland. Shryhane, with his Leninesque facial hair, secured himself a nice little turn as an extra. When I got my first work experience stint at the Observer aged about 14, I felt like I was in the presence of greatness.

Shryhane was, and is, Mr Wigan. He turns 77 this year and is still writing for the Obbie on a freelance basis, 25 years after formally retiring. But it’s not like the old days.

Sixty years ago, the young Shryhane took to the job like he was born to it, and inhaled news like oxygen. “If something happened in Wigan, people read about it in the Obbie,” says Shryhane. “I covered council committee meetings four nights a week, after doing full days at work. I covered 60 court cases a year. If you didn’t read about it in the Post and Chron or the Obbie, it hadn’t happened in Wigan. I didn’t get a penny overtime for all that extra work but I didn’t care at that age. I was just a byline junkie.”

And he wasn’t the only one. On the Observer alone at that point, the newsroom was 17-strong, including five photographers. Today it has one member of staff.

“I still look at the Wigan website about 50 times a day, but there is a lot of stuff that just has nothing to do with the town,” Shryhane says. “I do worry about the lack of accountability that is being put on authorities and official bodies, because the papers just don’t seem to be able to cover these things any more.”

It would be easy to blame the internet but the problems set in long before that. In 1966, the Wall family sold the Observer to a publishing company called United Provincial Newspapers. In 1998, the company was sold again to a venture capital outfit called Regional Independent Media. Johnston Press bought out that company in 2002. It was sold to JPIMedia, which in turn was bought by Northern Irish media mogul David Montgomery in 2020. It became a part of his National World portfolio, which contains dozens of newspapers across the UK.

The important date in all this is 1966, when the Observer ceased to be a family business. “In what old farts like you and me might call the good old days, newspaper owners wouldn’t actually make much money from their papers,” Steve Dyson tells me. “They would only make 3 or 4 per cent profit. They would generally be local businessmen who would set up newspapers almost as a contribution to society. And that’s where the industry has gone wrong over the past 30 or 40 years, because it passed into the hands of companies who wanted to squeeze every single penny out of them.”

Dyson is a former editor of the Birmingham Mail and now an industry analyst and trainer. He isn’t so naive that he thinks newspapers can or should be run as social enterprises in 2022. There is no getting that particular genie back in the bottle. What concerns him is that in the relentless chase for profits, the local media has lost its way.

I say local media because while the actual physical papers might be going the way of the dinosaur, the industry has entered the digital landscape. Every local paper has an online presence through a website and social media.

“It’s totally wrong to pretend that the groups that own local newspapers have got it right, because they haven’t,” says Dyson. “They’re squeezing every last penny out of it and there’s no longevity in what they’re doing to the local press, whether that’s online or in print. They’re not taking the job of the local press seriously, and because of that their local audiences are deserting them.”

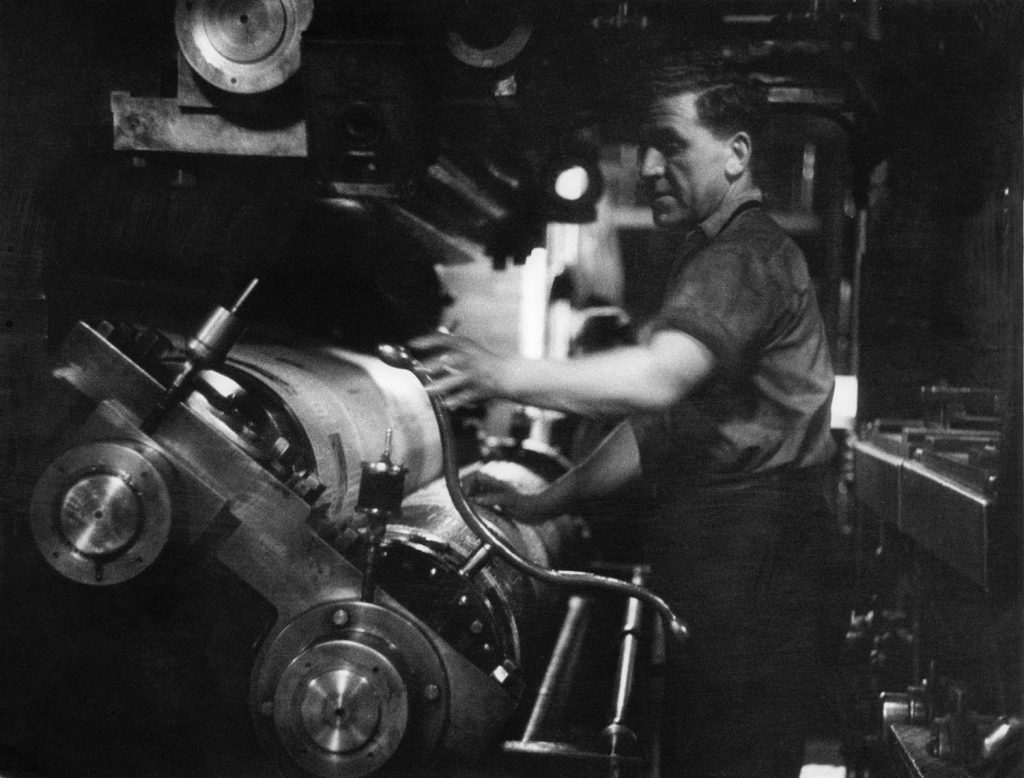

When the internet arrived, older reporters regarded it with the same weary distrust they had accepted the so-called “new technology” of the 1980s, which saw typewriters replaced with huge, boxy computer monitors and keyboards. The internet would not just change the way local newspapers worked, it would – in tandem with the drive for profits – effectively kill the industry.

Newspapers knew they had to be online, because everybody was online. But – and this was a national media problem as well as a local paper issue – how could they monetise that? Paying online was not an easy business. How do you charge for the online content of a newspaper that costs, say, 40p to buy on the street corner? PayPal wasn’t really a thing yet and people were distrustful of putting their bank details into websites. So what the newspaper industry did was take its only saleable resources – words and pictures – and give them away for free.

If the industry had its time again, would it do the same thing? Over the years I have heard many opinions from local media management. Some say they had no choice but to go online for free because most internet content was free; some say it was a big mistake.

But that was not the biggest problem. Local papers were funded by advertising; the cover price does not match the cost of printing, distributing and paying the wages of those who work for them. Advertising did that. And the three pillars of advertising were always cars, houses and jobs.

Once there would be pages and pages of these ads, whole pull-out supplements on different days – motors, homes and recruitment. The holy trinity that kept newspapers and newsrooms afloat.

And with the arrival of the internet, they all but disappeared. Because the car dealerships, the estate agents and the big recruiters such as health authorities and local councils realised practically overnight that they didn’t have to pay to put their wares in print that had a limited audience, both geographically and demographically.

Now they could put their houses, cars and jobs on their own websites. And if someone in Milton Keynes wanted to buy a house in Wigan, they could do a simple Google search. Car dealers didn’t have to advertise in both the local press and national magazines such as Auto Trader; they could put their entire stock online for anyone in the country to see. And when a body like the NHS has its own huge, government-funded website, why not just put all your recruitment ads from across the entire country in one place for job hunters to browse?

As the 21st Century dawned, local newspapers were fighting on two fronts: trying to stem the haemorrhaging of advertising revenue, and transitioning from a position of absolute authority in and sole custodianship of local news to a place where anyone out there with a blog and an internet connection could set themselves up as a rival.

“No one really understood the impact the web would have,” says Gillian Parkinson. “I think we saw the potential advantages of getting news out quickly and updating it, plus its value as a research tool, but I don’t think any of us understood what that would mean for our business model – i.e. one based on advertising revenue.”

Parkinson was the first woman news editor at the Lancashire Evening Post in Preston in 1992, then left to be editor of the Chorley Guardian in 1995. She joined the Wigan Observer and Wigan Evening Post as editor in 1997 and stayed until 2012, when she took over The Gazette in Blackpool and then became the first woman to edit the Lancashire Evening Post the same year. In 2013 she became editorial director of Johnston Press in the north-west, a position she held until she retired this year.

Gillian was the health correspondent when I joined the Lancashire Evening Post in 1990, swiftly moving to the newsdesk. I remember coming in at 8am to peruse the diary that she or one of her colleagues would have already marked up for the day: a reporter to call the emergency services every hour, on the hour; someone to attend magistrates’ court, maybe two journalists if it was a busy day; every inquest covered, every council meeting, health authority meeting, every Crown Court case.

“Yes we did cover everything,” she says. “But then, we had the resources to do it, mainly paid for by the fact that we had an advertising monopoly in the marketplaces we covered. If people wanted to advertise their services they had to come to us and did. That then created a relevance for the product with the public looking for things other than news, i.e. classified, jobs, property, cars, BMD [births, marriages and deaths] advertising as well as ROP [run of paper advertising]. So the two revenue streams – advertising and news sales – together provided money for a decent number of journalists. As soon as that monopoly began to erode, with the advent of Google, Facebook and even eBay, so did profits… and there was a gradual knock-on for resources.”

When profits started to shrink, owners cut costs. And that meant losing bodies. It seemed stupid to cut advertising staff, who were pounding the streets or hammering the phones trying to claw back revenue. So the axe began to fall on editorial departments. Fewer journalists inevitably meant a fall in the ability to cover everything in a provincial town. And with that the seeds were planted for the real crisis in local newspapers.

Most local newspaper reporters are desperate to serve their communities, in much the same way as those businessmen who set up these papers in the first place. Nobody gets into local journalism for the money. But increasingly the emphasis for staff is to get clicks on the company website at any cost. That means grabbing the reader’s attention, largely through social media, and if the story is not necessarily traditional local newspaper fare then so what? Which is why, when I peruse the Twitter feed of my local newspaper, I might see as many, if not more, links to stories about Love Island or the price of a Greggs pasty or the latest Hollywood shenanigans as stories about what’s happening in my community.

Steve Dyson says: “In local media these days, nobody seems to report car crashes or fires, nobody calls the fire stations and the ambulance stations every hour to see what’s going on. If you don’t cover inquests and court cases, you’re not only missing out on good stories but you’re also taking away those warnings, those deterrents, that used to come from such coverage.”

Gillian Parkinson adds: “I’ve never been a huge advocate of individual targets, but I understand why they are there – to drive performance and therefore revenues. I much prefer team targets for news, sport etc, where everyone works together to the common goal.”

Why targets? Why are eyes on the website so important? Because newspaper companies are trying to migrate their advertisers who still pay for ads in the printed products wholly online. When that happens, it will herald the death of the printed paper.

But to get those eyes on the website, and to meet their targets (sometimes in the region of half a million individual hits over a month), reporters are being trained to go for the sorts of stories that will pique the interest of an audience not necessarily limited to the geographical reach of the paper.

Parkinson is realistic about this. “Times have changed and most community organisations have their own websites – amateur sport is a classic example. Why would people come to us to read match reports? Better to cover this kind of content in another way – long read, photo gallery, feature etc – where you are using journalistic skills to provide something not available elsewhere.

“How many people actually read Women’s Institute reports in print? Probably as many as online – and they are almost certainly the people who were at the meeting and know what happened.

“So I think we have to be pragmatic on this. We haven’t got the resources to cover something which is of little interest to the public, so we have to decide how to make it interesting or look to provide a different kind of content.”

I left local newspapers in 2015, after a 26-year career, but efforts were already being made to replicate on the websites what was going on in other areas of the internet. The “listicle” suddenly became popular in local newsrooms, because that’s what did well for Buzzfeed, for example. Reporters were trained to do video reports and live blogs about pretty much anything.

But while local media was aping the internet, and turning its resources away from the traditional news coverage, there was yet another plot twist: the internet started to do local newspapers’ jobs for them.

That hyperlocal content – the WI meetings and the car crashes and the things that happened at the end of the street – began to be discussed and essentially reported via local Facebook groups and apps such as Nextdoor. From them evolved websites with strong media presences that covered the minutiae of community life in a chatty, personal tone. And, increasingly, that’s where many people are getting what they consider their local news from, while the local newspapers which used to do the job chase clicks.

What those sources of “news” don’t have, though, is the regulation that the local media is subject to, nor the skills of trained reporters and editors. Gillian Parkinson says: “It does concern me that people are getting most of their news online – from Facebook etc – which provides them with a constant stream of stuff they are already interested in and opinions they agree with. One of the great joys of reading a newspaper is discovering a great article on something you had no prior knowledge of and finding some new insight. That could never happen on Facebook. That is one reason why we are seeing such polarisation, because everything people read just reinforces their own prejudices instead of questioning them.”

There have been efforts to reduce the cuts to editorial staff, most notably through the Local Democracy Reporting Service (LDRS), set up in 2017 by the BBC. Under this scheme, the corporation funds reporters employed by local media groups – TV, radio, online portals as well as newspapers – to ensure that council meetings are covered and stories arising from local authorities are brought to light. When it launched properly in January 2018 there were ten local newspaper groups on board, and this was expanded by eight groups in July last year, bringing the total number of local democracy reporters funded by the BBC to 165.

Reporters file copy that can be used by any organisation that has signed up to the scheme, and to be accepted, media groups have to prove “financial standing and a strong track record of relevant journalism in the area they were applying to cover”, according to the BBC.

For years many newspaper groups have hated the fact that the BBC receives public funding through the licence fee, while they have to live or die on their own. This was at least a gesture from the BBC – around 1,000 brands currently benefit from the LDRS – but it’s not pure philanthropy. The corporation is making cuts to its own local news services as a response to the freezing of the licence fee, and gets to use all the LDRS stories too and as part of the deal can request bespoke interviews and coverage for radio and TV bulletins.

Google is also supporting local journalism at established papers with funding, and while this influx of public and private money into the local media industry is certainly going some way to stem the tide of falling numbers of bums on seats, there are questions about sustainability.

Steve Dyson welcomes the LDRS but he is disquieted by it, and for one simple reason: newspaper owners have got out of the habit of paying for those things, and if those schemes ended or the funding dried up, what would happen then?

“It’s a valuable service but it does give the owners an excuse not to cover that funding if it ever disappears,” he says. “What PLC will invest in reporters when they’ve already got rid of them?”

For Parkinson, there is another issue that threatens local newspapers: the lack of young people who want to work on them. She says: “When our court reporter left late last year, I got it signed off straight away and advertised. However, not a single person applied for the job. It used to be a top role, the same for news editor and even editor roles, but we don’t seem to be able to attract people like we once did.

“There are so many other potential roles around for would-be reporters – and let’s face it, it’s hard work because of the lack of resources – that I think trainees don’t see it as an attractive option. That’s a shame because other companies put huge value on those who train through our newsrooms as they know they will be getting good young journalists.”

The picture looks bleak for local newspapers. More and more are falling below the threshold of sales that makes them economically viable. It was of great sadness to Parkinson that the Wigan Evening Post was forced to go weekly, from six days a week, at the end of 2021. She says: “We had tried everything to save the Post as a daily – relaunch, cover price cut, increased paginations… but nothing increased sales or advertising enough to make it viable as a daily.

For Steve Dyson, his big worry is that the central plank of shifting everything online, not just editorial content but all advertising too, to eventually make the printed product redundant, is flawed at its core. “Because the whole ownership structure is based on profit, I just believe in the end they’re signing their own death warrants,” he says, “because once print has gone the advertising won’t be there. Advertisers won’t spend money online. It’s not replacing the money they spend in print; even now advertisers still spend 70 per cent of their money on print advertising so once that has gone where is the revenue going to come from?”

Parkinson, at least, sounds a note of cautious optimism for the future. She says: “Good journalism will continue. Most people access their news online now whether we print-lovers like it or not. The important thing is to position these community brands so that they continue online and try to provide the very best service they can for local communities.

“The way to do that is to provide quality content which people can’t find elsewhere – perhaps behind a paywall in some cases – to enable us to pay for more journalists to cover more areas of the community and for those journalists to be an integral part of those communities. I think that journey has already started and people are beginning to see the wood for the trees.”

The trick, of course, will be to convince all over again those communities who have fallen out of love with their local media to learn to trust it again, and to bring in young reporters with a fire in their belly to serve them. And it can’t happen a moment too soon.

As Francis Williams wrote in Dangerous Estate more than six decades ago: “Newspapers exist to be read. If they fail in that essential their failure is absolute whatever other merits they abundantly possess. Not for the journalist is the comfort that sustains the artist. He cannot appeal from the present to the future. He must match his moment. Moreover, newspapers are by their nature made at least as much by those who read them as by those who edit and write them. They are as good or as bad as their public allows, for the greatest newspaper in the world has no future if it cannot get and hold a public.”

David Barnett is an author, journalist and comic book writer. This piece was taken from the latest edition of the Tortoise Quarterly, our short book of long reads. You can pick up a copy in glorious, old-fashioned print in our shop at a special member price.