As private equity firms snap up oil and gas assets, they face growing pressure to clean up their act

- EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said Europe should adjust its rules on state aid to counter America’s green energy subsidies.

- The US accused Chinese companies of evading tariffs on solar panels by sending components to Southeast Asia to be processed.

- The UK’s political turmoil has delayed a project to connect Britain with a wind and solar farm in Morocco through an undersea cable.

Is ownership of the world’s oil and gas fields moving into the shadows? As activist and investor pressure grows on publicly listed energy companies like BP and Shell, restricting their ability to raise finance, private equity firms have been snapping up assets from Alaska to the North Sea.

Going private can free a business from the demands of having to explain a strategy to investors. Instead of facing market pressure to give cash back to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks, a privately run oil business is free to gamble on exploration, no matter what that means for the climate.

An analysis of oil and gas deals over the past five years shows assets flowing from publicly listed to private hands at a significant rate. Deals tended to lead to weaker environmental oversight, according to the research published by the Environmental Defense Fund, a US advocacy group.

There were more than twice as many deals where assets moved away from operators with strong environmental commitments than the reverse, the study finds.

By the numbers:

- Private equity firms’ oil and gas deals jumped from $30 billion in 2021 to $38.5 billion this year to date, according to Preqin.

- Energy majors ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Shell, Total and Eni sold assets totalling $16.3 billion last year and have sold $15 billion of assets so far this year, according to Wood Mackenzie.

- These six majors currently have plans to sell assets totalling a further $30.5 billion.

But even in private markets, the longer-term trend appears to be a shift away from fossil fuels.

That’s partly a consequence of recent history: private capital helped drive the fracking boom in the US and many firms made heavy losses when an oil glut eight years ago brought crude prices crashing down and wiped out profits in the shale sector.

Some of private equity’s giants have since retreated from fossil fuels in favour of renewables.

- Blackstone stopped doing new deals in oil and gas exploration and production in 2017 and

- told clients this year that its private equity arm will no longer invest in the upstream part of the sector.

- Apollo Global Management is avoiding fossil fuels in the $25 billion fund it is currently raising. That shift is likely to persist despite a backlash from Republican-governed US states (see nibs, below).

Market forces are not the only factor. Private equity may feel like a shadowy world. But the money they deploy comes out of institutions like pension funds that are subject to social pressure. One private equity insider notes that university endowment managers have become increasingly conscious of how students will react to an investment decision.

Last month, an alliance of asset owners including Aviva and CalPERS, the biggest US pension fund, urged private equity groups to raise their level of climate ambition. Private equity should use their influence to set climate on the agenda of all companies, the asset owners said.

They urged private equity not to finance new oil investments “beyond those already committed by the end of 2021”.

The traditional private equity approach to a business is to turn its performance around and then sell on public markets at a favourable time. That’s harder to do with fossil fuels as the pool of publicly listed buyers shrinks. This is likely to lead to pressure from private equity firms to reduce emissions coming from the oil and gas businesses they run. Even in the more opaque world of private capital, there may ultimately be no hiding place for fossil fuels.

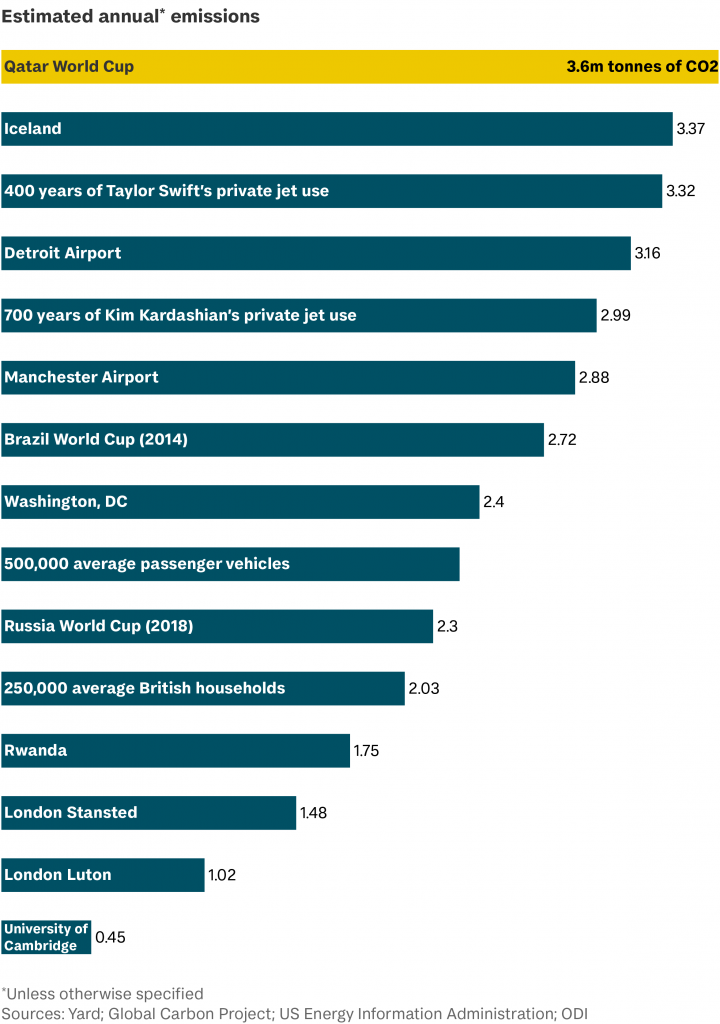

Football’s footprint: how much CO2 will Qatar’s World Cup emit?

A message from

Companies are investing more time producing climate risk disclosures based on the TCFD recommendations. However, these disclosures are not translating into actionable strategies to accelerate decarbonisation. The EY report analyses the reasons behind this by reviewing the disclosures made by 1,500 companies across 47 countries.

This is sponsored by EY