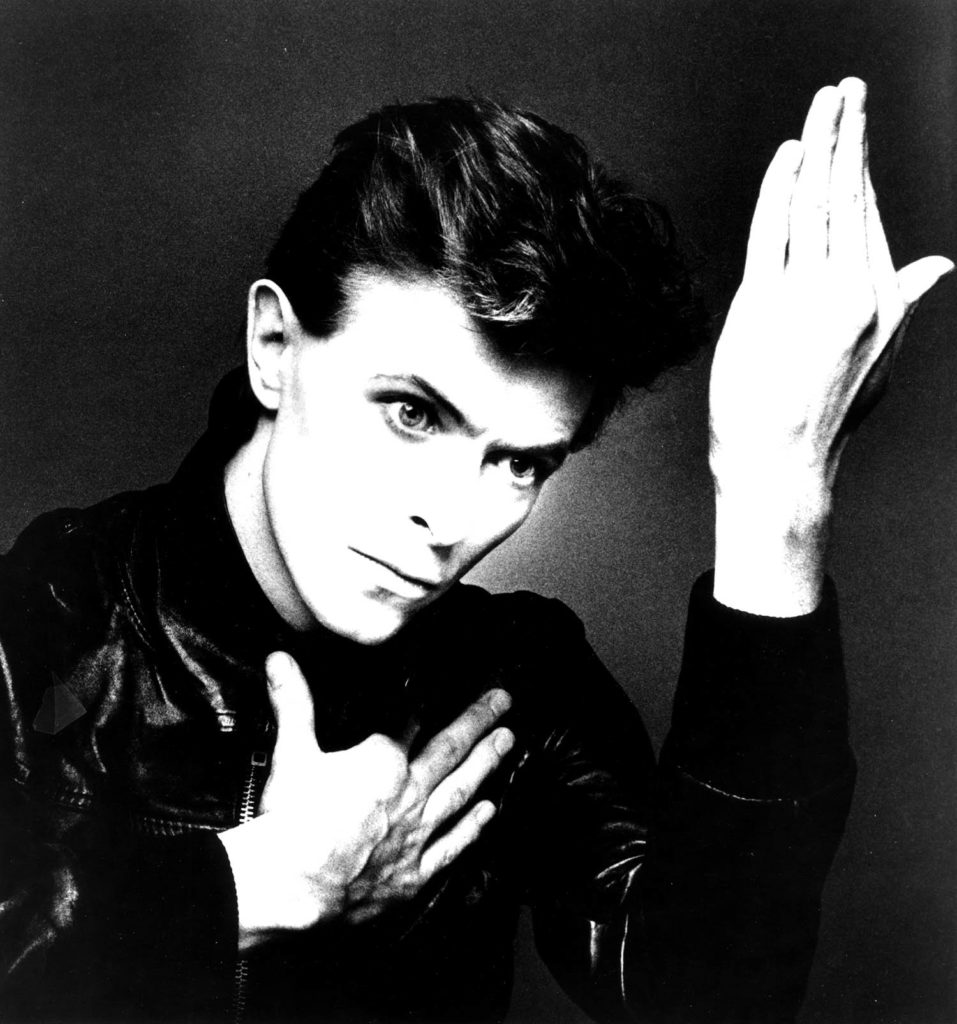

Moonage Daydream is an extraordinary, kaleidoscopic voyage through the mind and art of David Bowie

Sheer audacity was such an important part of it; of the whole phenomenon. Brett Morgen’s stunning documentary Moonage Daydream (Imax theatres, 16 September; general release 23 September) opens with a portentous quotation from David Bowie in 2002, riffing for all he was worth on Nietzsche’s aphorism that “God is dead… and we have killed him.”

And you think: how did he always get away with it? How did David Jones, the Man who fell to Earth from Bromley pull it off? And then you remember that the song from which the film takes its title begins with the declaration: “I’m an alligator.” Epic chutzpah was always the cheeky heart of Bowie’s soaring ambition, play-acting and tap dance with profundity.

To be the first filmmaker allowed full and official access to the Bowie estate (sold in its entirety to Warner Chappell Music in January for an estimated $250 million) and an archive that includes five million items must have been daunting indeed; and it helps that this is not Morgen’s first rodeo. His movie on the film mogul Robert Evans, The Kid Stays in the Picture (2002) is a modern classic, while Cobain: Montage of Heck (2015) is the best documentary to date on the Nirvana frontman.

No director approaching the subject of Bowie’s life and work could possibly hope to be comprehensive. Morgen, to brilliant effect, chooses the different path of maximalism: which is to say that, from the opening minutes, and the strains of ‘Hallo Spaceboy’ from the underrated 1995 album, Outside, he takes us on an intergalactic, sometimes psychedelic voyage through Bowie’s life, imagination and artistic universe.

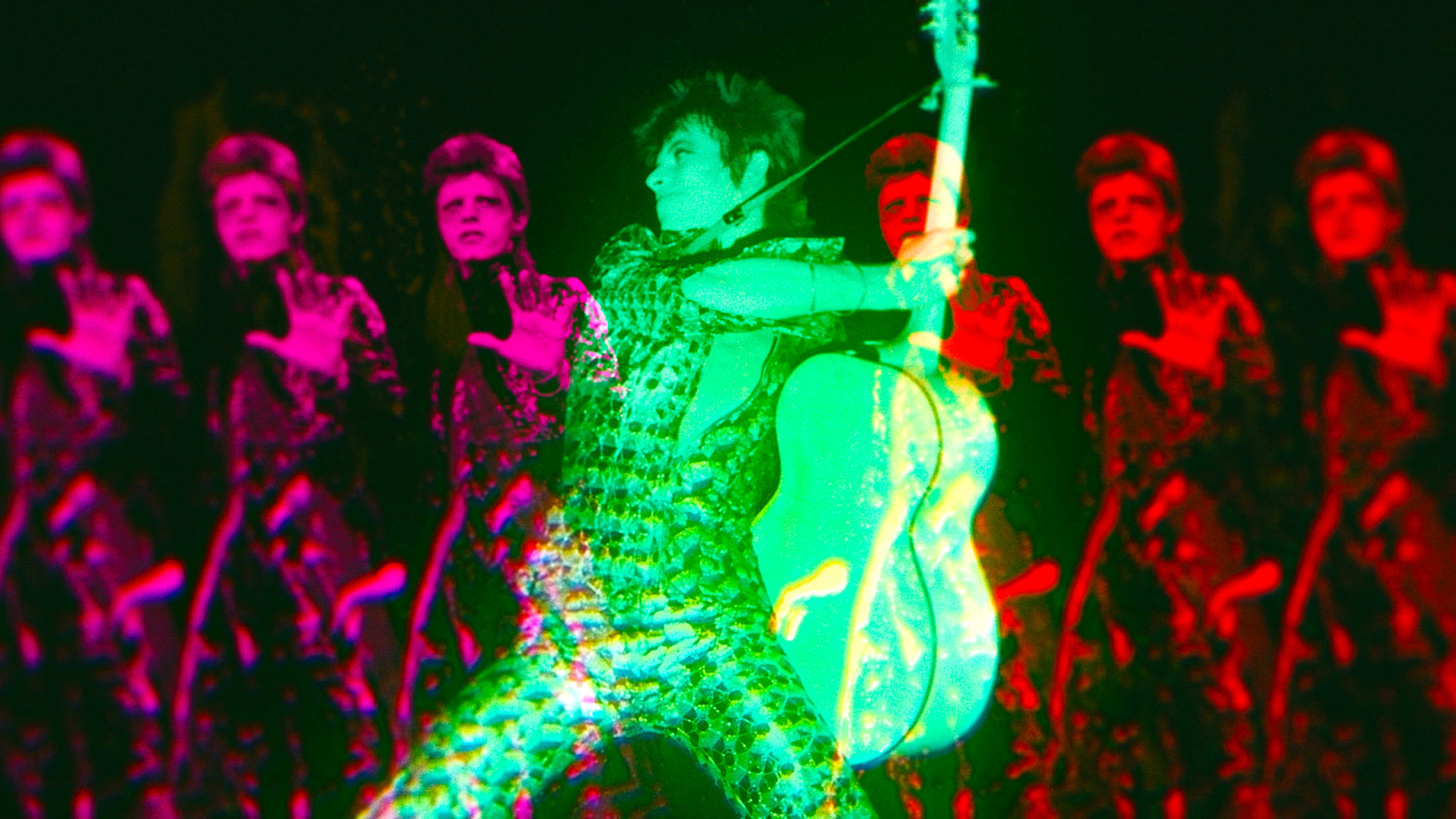

Like the eponymous Starman, the director knows he’s going to “blow our minds”, and is delighted to do so. Moonscapes, wild colour washes, jump cuts, interspliced footage, leaps across space and time: we are bombarded with all of it in an experience that is intended to make a dazzled Major Tom of each and every one of us.

Morgen also avoids all the tired narrative arcs about Bowie: that his genius was to be found in his mutability, in his persistent reinvention from Ziggy Stardust to Philadelphia soul singer to the Thin White Duke; or that the heart of the matter was his terror of hereditary mental illness, a terror personified in his schizophrenic half brother Terry Burns (a wildly speculative theory that cannot survive a reading of Dylan Jones’s David Bowie: A Life, by far the best biography of the musician); or, most egregriously, that Bowie got boring when he got sober and found true love with his second wife, Iman.

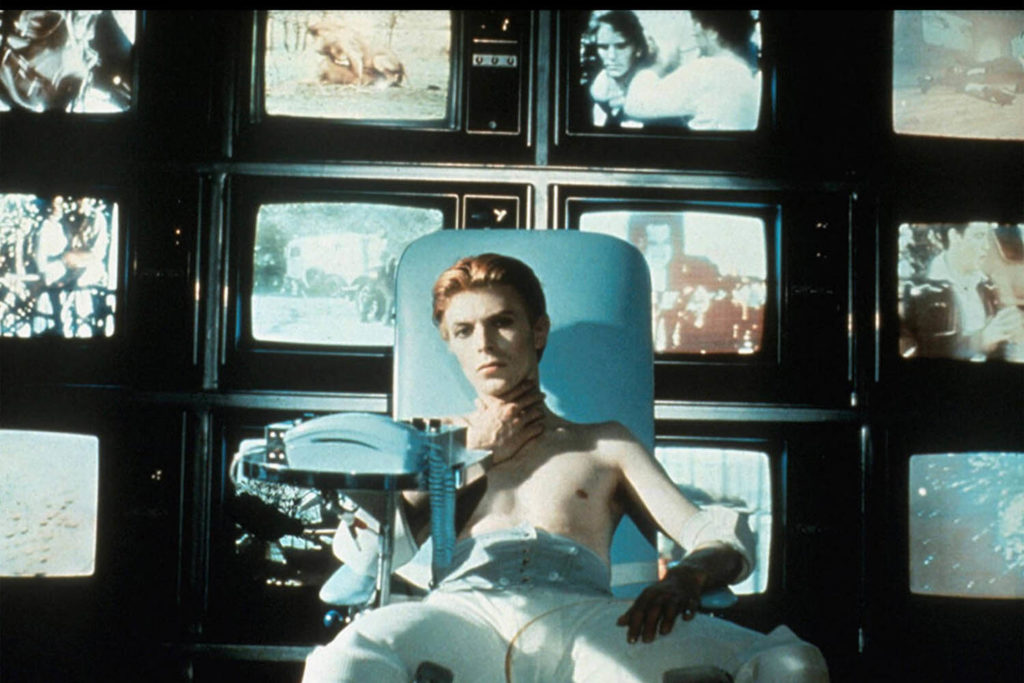

You only have to listen to his final album, the jazz-influenced Blackstar, released two days before his death in January 2016, to realise how absurd that particular claim is. In his final months, he was also working on Lazarus, a stage musical inspired by Nic Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976); returning to the art form that, in his teens, he had imagined would be his vocation.

And watch this 1999 Newsnight interview with Jeremy Paxman, in which Bowie predicts with uncanny accuracy the impact of the digital revolution: “I think the potential of what the internet is going to do to society, both good and bad, is unimaginable,” he says, a full five years before Facebook was invented. When a sceptical Paxman argues that the web is merely a tool, Bowie replies that it is “an alien life form” that “is going to crush our ideas of what mediums are all about.”

Instead of retreading old paths, Morgen addresses the greater subject of Bowie as an artist, and his evolving notion of what art was, and what, if anything, it was for. To his credit, he ditches entirely the standard talking heads format of the rock documentary, preferring “show” to “tell”.

Naturally, we hear plenty from Bowie himself, and see images of him that have rarely or never before been used. Especially powerful is footage shot by D.A. Pennebaker when he was making Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1979) and from Gerry Troyna’s obscure Ricochet (1984) which shows blonde Eighties Bowie wandering spectrally through Asia: queuing solo at Bangkok airport, or visiting a Javanese musical group.

What Morgen captures best is Bowie’s omnivorous, insatiable appetite as a collector, curator and synthesiser of art. His hinterland was positively planet-sized, his artistic erudition prodigious. As he put it in a 1999 commencement address at Berklee College of Music in Boston, he had been “on a crusade to change the kind of information that rock music contained” (on this and many other aspects of his cultural significance, try Paul Morley’s The Age of Bowie: How David Bowie Made a World of Difference).

As he says in a clip from Alan Yentob’s 1975 BBC documentary Cracked Actor that is included by Morgen: “There’s a fly floating around in my milk. There is a foreign body in it, you see. And it’s getting a lot of milk. That’s kind of how I felt. A foreign body. And I couldn’t help but soak it up.”

On that occasion, he was talking about American culture. More generally, his work was (and is) a gateway to Jacques Brel, Kabuki theatre, Jean Genet, William Burroughs, John Coltrane, Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground, the mime of Lindsay Kemp, À rebours and Joris-Karl Huysmans, Jack Kerouac, and a thousand other influences.

Moonage Daydream honours this with a wealth of cut-in cinematic references – to F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, Buster Keaton (very important to Bowie), Nagisa Ōshima (in whose Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence he starred), Stanley Kubrick, Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) and Rutger Hauer in Blade Runner (1982).

As the late cultural theorist Mark Fisher put it in 2013: “Bowie’s serial passage through personae, concepts and collaborators only telegraphed what is always the case: that the artist is synthesizer and curator of forces and ideas.”

That said, the purpose of this eclectic cultural blizzard was never to intimidate the listener or the audience. As Bowie says in the movie: “It was a pudding of ideas”. Any source would do, however cerebral or trashy, as long as it contributed to something new or exciting: “We were creating the 20th Century; everything is rubbish, and all rubbish is wonderful”.

Nor was the primary purpose of this joyous mash-up to arrive at an intellectual destination. As Bowie recalls of his early fascination with Fats Domino, it was the very fact that he couldn’t pick out the lyrics that made the legend of New Orleans so mesmerising. Mystery was the thrill. It was imperative, too, to look beyond cultural comfort: “If you feel safe in the area you’re working in, you’re not working in the right area.”

Though he freely admitted to fickle experimentation with different religious teachings and secular philosophies, Bowie’s real insight was that art does not deliver pat answers to life’s great questions. It could identify patterns and sources of pleasure. It was a way of coming to terms with and embracing transience. And – far from imposing order on the universe – it had the capacity to help us reconcile ourselves to the opposite: “our refusal to accept chaos… [is] one of the biggest mistakes we’ve made.”

At a moment of national mourning of a different kind, it is striking to reflect how deeply many people, all over the world, still grieve over the loss of Bowie, more than six years after his death aged 69. It is a measure of his abiding significance and its breadth that he defies all attempts at categorisation, or glib analysis.

What Moonage Daydream shows beyond doubt is that he was never a nihilist; that there is a difference between the trickster and the cynic; and that when the Starman “told us not to blow it/ ‘Cause he knows it’s all worthwhile” he was speaking for the singer, too.

As Bowie put it: “It’s what you do in life that’s important. Not how much time you have.” You leave the movie house marvelling afresh at how much he did, its continuing importance, humming the tunes as you walk out into the moonlight, the serious moonlight.