What just happened

- The EU proposed an embargo on Russian coal and sanctions on Putin’s daughters, as Zelensky called for Russia to be removed from the UN Security Council.

- Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch accused Ethiopia of war crimes in Tigray.

- A couple identifying themselves as Anton and Nastiya got married in the ruins of Kharkiv.

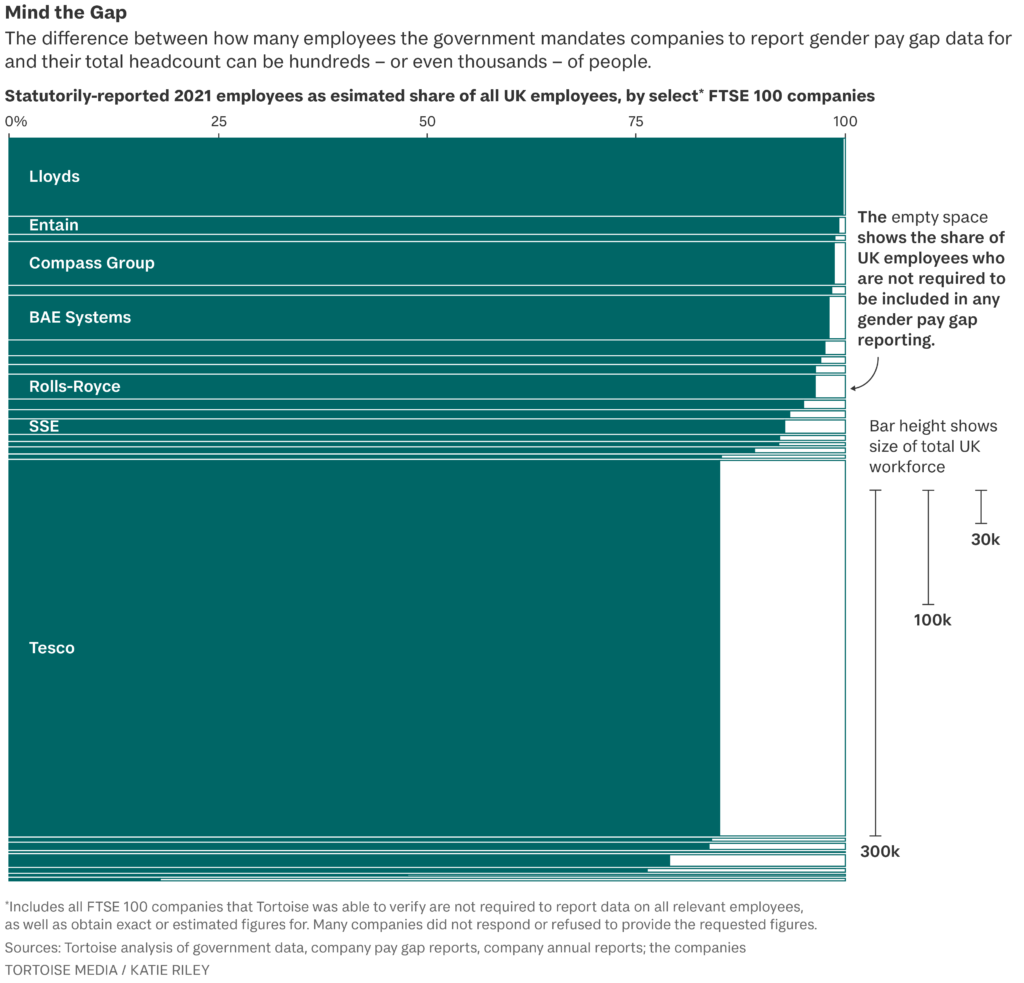

Thousands of FTSE 100 employees at companies including Tesco, WPP and Schroders are being missed by pay gap reports because rules do not require them to be included, Tortoise has found.

The rules mean employers can avoid publishing a gender pay gap figure that covers their whole workforce. They also allow gaps to go unmeasured when big companies report as multiple smaller ones.

New pay data that UK companies were required to produce this week showed that the gender gap at Britain’s banks has barely shrunk in five years and men’s bonuses at City firms are still at least 50 per cent higher on average than women’s.

But holes in the data mean the information provided by some of Britain’s biggest companies often doesn’t give the full picture:

- Tesco provides no figure for its full UK-based workforce, but instead reports 12 separate pay gaps covering a total of around 275,000 employees, 85 per cent of its total of approximately UK-based 325,000 employees.

- WPP, the advertising group behind Dove’s “courage is beautiful” campaign, reports 13 separate pay gaps, with the data covering under 80 per cent of its UK-based workforce, leaving out approximately 2,000 employees.

- Schroders, the London-based fund manager, reports data that covers just 76 per cent of its UK-based workforce, leaving more than 700 employees unaccounted for.

Why are people being left out? The law states that all companies with over 250 employees must report their pay gap figures to the government.

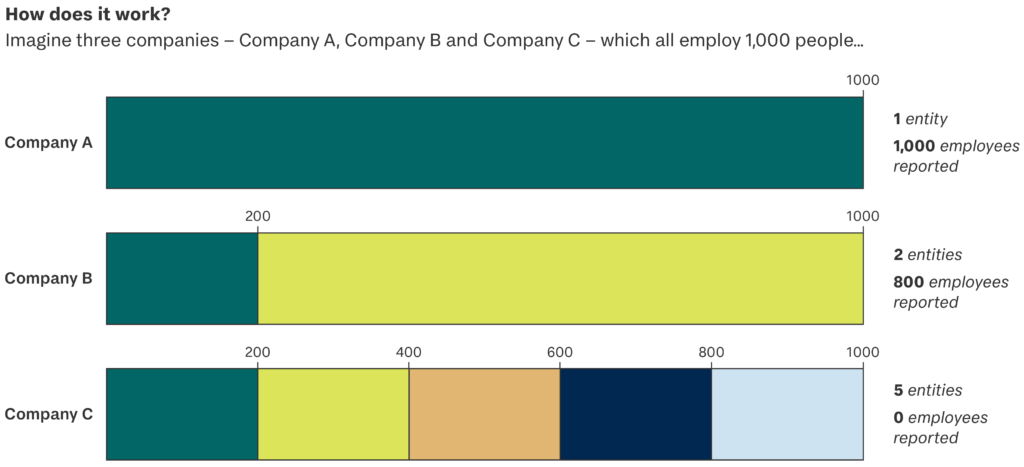

Often, large companies are made up of a web of multiple smaller ones, meaning anyone employed at a constituent company with fewer than 250 people won’t be counted.

Part-time, self-employed and full-time employees are counted, but those being paid a reduced rate aren’t. That includes anyone who was on furlough with lower pay when the data was collected – and more women than men fall into that group. Charlotte Woodworth, Gender Director at Business in the Community, says the exclusion of furloughed employees from this year’s data means the starting point for understanding the gender pay gap across UK companies is with “one arm tied behind our back”.

The way the data is reported can also make it impossible to find a single pay gap for a large company. Tesco plc, for example, consists of a group of over 100 UK-based companies rather than a single large one, so is not required to publish a UK-wide pay gap for its whole workforce.

Instead, it reports separate pay gaps for each of its constituent companies that have at least 250 employees, including Tesco Bank, Tesco Stores, and Tesco Family Dining.

Anyone working at a company within Tesco’s group structure with fewer than 250 people would have been missed out because the rules don’t require the data to be reported.

To get an idea of the scale of the problem, we asked every member of the FTSE 100 about the data they do publish. The majority of FTSE 100 companies consist of a group of different-sized companies, meaning they aren’t required to publish pay gap data on their full workforce.

Nor are they required to publish a consolidated pay gap number for the whole group. A sizeable number of companies chose voluntarily to report a consolidated UK figure covering their full workforce, including all subsidiaries. But because it’s not required by law, many don’t. Of the FTSE 100, we found 35 companies that chose not to publish a figure for their UK-wide gender pay gap.

Even when companies voluntarily report on their full UK-based workforce, the numbers tend to be buried in pay gap reports or annual reports on their websites.

To note: in 2019/20 when companies were not required to produce gender pay gap data because of the pandemic, nearly half didn’t.

Why it matters

- Fairness. Pay gap reporting is a vital window on workplace inequality, for employers as well as workers. It’s “important for corporate groups to be aware of, and if necessary justify, pay differentials between different parts of the larger organisation,” says Lorraine Heard of Womble Bond Dickinson, a law firm.

- Cost of living. Now more than ever, Woodworth says, pay gap reporting “reminds us about the power of financial security – and financial insecurity”.

- UK lags. Researchers at King’s College London’s Global Institute for Women’s Leadership have criticised the UK’s uniquely “light-touch approach” compared with other rich countries on data collection requirements for employers, and on actions expected of them when gender pay gaps are identified.

This isn’t the first time these issues have been raised. When the rules were being drawn up in 2016, several companies including BT raised concerns during a government consultation.

BT suggested they should be required to publish both at the group level and at the subsidiary level to avoid parts of the business being missed out, but the concerns were dismissed.

The battle has since moved to parliament. Stella Creasy, the Labour MP, has introduced a bill to reduce the employee threshold to 100 for mandatory reporting. The result would be to capture many smaller companies as well as the smaller entities within large ones – but for now there’s little prospect of the bill becoming law. The pay gap gap persists.

Rajapaksa Inc.

The ripple effect of the war in Ukraine has reached Peru (see below) and Sri Lanka, where food and fuel shortages worsened by the conflict are contributing to the most serious economic crisis in 70 years. Angry protests outside President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s residence led him to declare a state of emergency last week which he’s since suspended, but the crisis continues: most of Rajapaksa’s cabinet has quit, a replacement finance minister lasted barely 24 hours, the currency is in free fall, inflation is out of control and bankers fear the country is close to defaulting on an international bond payment. The immediate problem is an acute shortage of foreign currency rooted in aggressive tax-cutting by the last-but-one finance minister, Rajapaksa’s brother Basil. Sri Lanka is now so short of money that it has started closing embassies to cut costs. But the larger problem is an economy dependent on food and fuel imports, at the mercy of commodity price inflation, run for too long by one dominant political dynasty and still reeling from the devastating effects of Covid on tourism and public health.

Standing with Putin? Really?

Early last month two Twitter hashtags – #IStandWithPutin and #IStandWithRussia – started trending in the information war being fought alongside the physical one in Ukraine. They stood out as rare in a Twitter landscape dominated by enormously successful Ukrainian and pro-Ukrainian memes, themes and hashtags. Who or what was behind them? Carl Miller of the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media set out to find out. He looked at 10,000 Twitter accounts that have shared these and other pro-Russian tweets, traced them back to their linguistic roots and found three geographical clusters – in India, Pakistan / Iran, and South Africa (but including Ghanaian, Nigerian and Kenyan users). Many of these accounts already seemed fond of vivid anti-Western and anti-colonial posts. Miller reckons many are also being paid to post. His preliminary conclusion for the Atlantic: Russia is busy currying online support and spreading misinformation, but mainly outside the West.

Mood detectors

People suffering from depression tend to show it in their speech. It’s more monotone and quieter than normal, and they pause and stop more often. People suffering from anxiety tend to speak fast and have trouble breathing. And AI can tell. The NYT has a piece on new and new-ish AI-powered apps that are supposed to be able to tell if your mental health is suboptimal not from what you say but how you say it. Ingrid Williams, the reporter, gamely tries the Mental Fitness app from Sonde Health. It scores her mental health from 0 to 100 on the basis of the liveliness of her voice. She gets a “not great” 52 in about a minute, and promptly worries about why. The app recommends going for a walk and decluttering her personal space. Williams tries other apps too and notes that while they’re no substitute for qualified human therapists they could bring a measure of objectivity to a triage process that for some patients is too subjective, and lower the threshold for referral to real human help. Verdict: promising but unproven.

Crispr babies

In 2018 the Chinese biophysicist He Jiankui told the world he had produced gene-edited babies. More specifically, he said a woman had given birth to twins that would be resistant to HIV infection. Jiankui was sentenced in 2019 by a Shenzhen court to three years in prison for “illegal medical practice” in pursuit of “fame and profit”. MIT Technology Review revealed this week that he has been released. China’s health ministry banned him and his team from ever working with human reproductive technology again, but research elsewhere with the Crispr gene editing technology he used has continued apace. Advances have been made since 2018 in trials to tackle chronic pain, hereditary blindness and blood diseases. These trials don’t deal with reproduction, as Jiankui did, but a Russian scientist, Denis Rebrikov, has raised eyebrows with plans to gene-edit embryos of deaf parents to exclude the genetic mutation that causes hearing loss. Proof of concept is still some way off. As one scientist put it, the complexities of genetics “may ultimately save us from the hazards of human hubris”.